What's In A (Lesbian) Word?

On The L Word and Other Queer Phrases

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet and monthly playlists. You can also buy PDL stickers.

The language we use to describe ourselves says a lot about the set of relations that define our culture. As far as gender and sexuality go, the notion of identity as a distinct category of being is a fairly recent invention. According to Michel Foucault, discourse about human sexuality began to proliferate in the 19th century, especially within the scientific and medical fields. While naming homosexuality as a taxonomic category gave the state more power over such individuals, this development also had an unintended side-effect, which was the emergence of a more social category – identity.

Of course, language that refers to gender and sexual practices is not a new phenomenon. The most famous of these ancient terms are the Greek eromenos and erastes, which refers to a younger, passive male partner and an older, active male partner. But words like these had more to do with one’s actions and their position within a social hierarchy than they did with our more modern idea of identity as an innate state.

Contemporary language about gender and sexual identity has become increasingly fraught, especially because these terms rarely have a set definition and are used in a variety of contexts. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Indeed, one of the most fascinating characteristics of contemporary identity language is how these words evoke historical, personal, and communal relations as their meanings evolve over time.

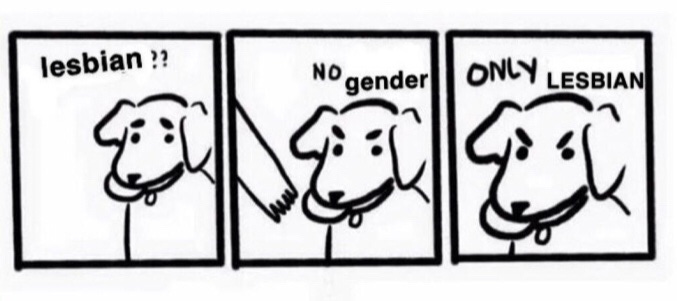

I titled this newsletter Paging Dr. Lesbian because I wanted to center a word that is often erased or overlooked for a number of reasons. In my writing, I use a variety of different words like lesbian, queer, and sapphic to describe individuals, groups of people, or forms of media. The reason I don’t always use the word lesbian is to include women or non-binary folks who are attracted to women but may not identify as such – bisexuals, pansexuals, etc. But, at the same time, I try to use lesbian as much as possible in order to counteract the notion that it is some sort of ‘dirty word.’ I used to use “queer women” or similar words in my academic work because it’s a common term in academia, but I have mostly ceased using this phrase because it doesn’t include non-binary lesbians, a gender-bending idea I’ve written about before.

In order to get a better handle on what these words mean and have meant to those in our community, I decided to take a two-pronged approach. First, I dug into the history of these terms to consider how their use has changed over time. Then, I conducted a brief survey about these words and asked respondents to provide definitions and explain if and when they use them. (I should note that this survey is far from comprehensive due to its small sample size and the bias of my sample pool. I posted the survey on Twitter, Reddit, and in this newsletter’s chat.) What follows is an odyssey through the annals of lesbian language.

The origin of the term lesbian is fairly well known. Sappho was an ancient Greek poet from the island of Lesbos. Though most of her poetry was lost, fragments remain, and her work is now read as archetypically lesbian in its content. Prior to its definition as it relates to homosexuality, the word lesbian was used proverbially to refer to women who were sexually promiscuous and performed oral sex on men, a stereotype mapped onto the women of Lesbos. The first published use of the word lesbian in a way we would understand today comes from a 1732 book called The Toast, though it wasn’t until the 1800s that the word became more commonplace.

In the mid to late Victorian era, Sappho’s poems were rediscovered by members of the Parisian literati. Lesbian trailblazers like Natalie Clifford Barney set about reading and translating Sappho’s works, and lesbian literature was a titillating trend, at least for a time. It was also during this period that sexology was developing, and the word lesbian was used in a medical dictionary and several books on psychology in the 1890s. Though those in the medical establishment were not using the term as a means of empowerment for their subjects, lesbians themselves were able to find power in the word, in part due to Sappho’s renewed popularity around the turn of the century. The prevalence of the term increased further in the 1980s and peaked in 2000, with its usage decreasing significantly between 2003 and 2014.

Notably, the definition of lesbian has not always been as strict as some see it today. Political lesbianism was a movement within second-wave feminism that encouraged women to separate themselves from men and live as lesbians by choice, and Adrienne Rich’s theory of the lesbian continuum highlighted the vast set of women-to-women kinships that can be defined as lesbian relations.

When I asked respondents to define the word lesbian, the answers varied. One or two people used the words “female” or “biological woman” to describe the term, but many others stayed away from a strict definition of woman altogether. (I will note here that Paging Dr. Lesbian believes that lesbianism is an expansive idea that should not be defined by biological essentialism.) The terms “women/female aligned” and “non-man loving non-man” were also used, as were some more abstract definitions. One person noted it is “deeply tied” to gender, history, and strength, while another said it “slides smoothly” and is “hot but also tender.” Another respondent noted it is “a radical way of seeing/experiencing the world & gender.”

In regards to personal usage, several respondents noted that it felt derogatory to them growing up, which has affected their relationship with the word. One worried it comes off as TERF-y so they use the word queer instead, and another highlighted how they appreciate the history of the word and how it unites a community. A lot of contemporary discourse about the word lesbian has sadly focused on TERFs (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists) who have defined the term in the most exclusionary, misogynistic way possible. We know from looking at history that trans and gender non-conforming folks have always been a part of the lesbian community. Claiming the word lesbian and emphasizing these rich histories continues to be a radical act, even as certain aspects of “LGBT” culture have become more mainstream. Indeed, the word lesbian is still rarely used in television, film, and digital media, even as queer representation has supposedly improved.

Like lesbian, sapphic has a long history, but its popularity has been much more recent. The term first emerged in the 16th century specifically as a way to describe Sappho’s poems. Sapphic was first used to describe lesbians in the 1890s, again around the time of the Sappho Renaissance and the influence of sexology. Lesbian and sapphist were used interchangeably around this time, though lesbian has been the more popular term in every decade. Given that bisexuality is a relatively new concept as far as identity goes, it’s unlikely that sapphic was used in the 20th century to denote all women who are attracted to other women (not just lesbians), as it is often used today. Fast-forwarding to the 21st century, there seems to have been a spike in usage in the 2010s, specifically after 2014 and primarily on the internet.

According to a survey done by Autostraddle, 60% of respondents noted that they use the term primarily to describe events or behaviors. A majority of participants also reported that they use the word as an “umbrella” term, that is to describe all women who are attracted to other women and/or non-binary people. My survey respondents generally concurred with this consensus. One person wrote that they use it to describe things rather than people, while another suggested they would use it to describe art but not themselves. Someone else suggested it has more to do with “social and cultural spaces” than a distinct sexual orientation.

The word sapphic also seems to have a distinct feeling to folks. One individual noted it gives them a “romantic feeling,” while another called the word “pretty.” One respondent described it as a “devotion to femmes,” while another called it “cute.” On the flipside, one person suggested that it is used in place of lesbian because it seems “softer” or “more feminine,” and “many people are afraid of the word lesbian.” Sapphic is an interesting example of a word that has a nominally inclusive meaning but may or may not feel right to certain folks. It’s likely that racial elements are at play in these discussions as well, as considerations about who is and is not seen as safe, palatable, or nonthreatening often hinge on racial difference. If sapphic sounds soft, feminine, and perhaps subliminally white, this certainly affects who feels comfortable under this umbrella term.

WLW is a term that is primarily used as internet slang. It stands for either “woman-loving woman” or “women who love women” depending on the context. The origins of the term are contested. A few years ago it was suggested that the phrase WLW originated in the Harlem Renaissance among black lesbians. This idea frequently circulates online, but the undergraduate-level paper cited in these claims has since been taken down, so it’s difficult to ascertain whether there is any truth to this idea (though it’s certainly possible).

What we know more concretely is that terms like “women loving women” or “women who love women” were used by lesbian feminists in the 1970s. What’s notable about uses of the term today is that it is almost always used as an acronym rather than the full phrase, which means connections to earlier terms are less visible. As modern online parlance, the phrase seems to have gained popularity in the 2010s on sites like Tumblr and Twitter. It is often used to describe fictional characters or relationships – as in “wlw couples” and the like. It is much more commonly used than the alternative, “mlm” (men who love men), and is theoretically inclusive of lesbians, bisexuals, and pansexuals. Significantly, the term does not include non-binary people, at least formally speaking.

When I asked about the term in the survey, most participants noted that they would never use the term to describe themselves and in general don’t use the term much at all. One respondent suggested that “WLW” is often used in place of “lesbian” to seem more palatable,” a substitution they’re not on board with. This seems like a probable explanation for the term’s popularity, especially as younger people frequently express discomfort with the term lesbian. (One participant suggested there is a generational divide with this term, with it being used primarily by Gen Z/Millenials.) WLW is often used as a descriptive term rather than an identity marker, which fits with the idea that it is less threatening than a term like lesbian. Moreover, unlike some of these other terms, the history of WLW – whatever that may be – is not invoked by these modern utterances. While our digital lives are indeed a part of our “real” lives, WLW is a term that has limited resonance in offline lesbian or queer spaces.

Queer is another term that is frequently up for debate, and these debates have in some cases raged on for decades. If you know anything about British queer history, it might not surprise you that the term queer dates back to the most prominent gay figure of the late Victorian era: Oscar Wilde. The first use of the word queer to describe homosexual identity is said to have been at Wilde’s infamous 1895 trial, where a letter describing Wilde and his associates as “Snob Queers” was read aloud in court. A later source indicates that the term didn’t become commonplace as a slur until around 1914. Despite its derogatory connotations at the time, a 1934 letter provides at least one example of the word being used as a means of self-identification.

It wasn’t until the 1980s and on that there was a concerted effort to reclaim the term. This movement also coincided with the advent of queer studies within the academy, wherein scholars argued that queer is not only a noun but a verb, and to queer something means to deconstruct or subvert it. The prominent AIDS activist group ACT UP became Queer Nation in 1990, reflecting this turn to a more expansive, destabilizing linguistic pedagogy. A Queer Nation leaflet distributed at the 1990 NYC Pride march reads:

“Well, yes, "gay " is great. It has its place. But when a lot of lesbians and gay men wake up in the morning we feel angry and disgusted, not gay. So we've chosen to call ourselves queer. Using "queer" is a way of reminding us how we are perceived by the rest of the world. It's a way of telling ourselves we don't have to be witty and charming people who keep our lives discreet and marginalized in the straight world. We use queer as gay men loving lesbians and lesbians loving being queer.”

Their use of the term is both rhetorically and materially inventive. Later, they write that “Yeah, QUEER can be a rough word but it is also a sly and ironic weapon we can steal from the homophobe's hands and use against him.” The manifesto is illustrative of the radical origins of the term as a social or political tool. Though the word gained mainstream popularity by the end of the decade – the British Queer As Folk premiered in 1999 and the American version in 2000 – this history is important to keep in mind.

When I asked respondents to define the term, the answers were as diverse as one would expect. Participants used words like “amorphous,” “umbrella,” “broad,” “inclusive,” and “being at odds.” One person defined it simply as a “slur,” while another pointed to its association with community. One individual noted that the reclamation of the word was “beautiful” before it became the “flattening” term it is today.

As to whether they use the word to describe themselves, most respondents said yes, but lesbian was more commonly used than queer overall. One individual noted that it's too vague while another took issue with its negative connotations. One person said they use it in a political rather than personal sense, while another said it felt “accurate and expansive.” On the other hand, one individual noted that they find lesbianism to be a more expansive term than queer, as queer feels too vague or fluid to them. One respondent noted that it feels more inclusive of non-binary people, and another suggested it’s helpful when referring to a collective.

Many respondents noted that how these words are used in the world affects their relationship with them. While several individuals noted that lesbianism still feels like a taboo word but they use it regardless, others felt the same way about queer. Every person had a slightly different opinion on which words were and weren’t inclusive, and which words have a deep or personal meaning to them. Several users noted that queer in particular doesn’t seem to have the same radical connotations it once did. Though we have more access to history than ever before, queer terminology does feel more ahistorical as of late, and one’s relationship (or lack thereof) with queer and lesbian history is likely a factor in their affinity with these words.

Dyke is one of the most loaded terms in the lesbian lexicon, and its history is similarly charged. There are several hypotheses about the origin of the term. The most widely accepted is that dyke is a shortening of bulldyker (also bulldagger), black American slang from the 1920s referring to women who have sex with women. This term was often used to describe masculine women in particular. Another theorem suggests that the word comes from morphadike, a misspelling of hermaphrodite, a term that refers to an individual who has both male and female sex characteristics. Another explanation is that it comes from the Celtic queen Boudica, a warrior who was very threatening to men, or the phrase “diked out” meaning decked out or overdressed, especially in men’s clothing. In the following decades, the term was used as a slur by straight people to defame lesbians or non-conforming women, though it was later reclaimed by lesbians who found power in the word.

A 1979 essay by JR Roberts stakes this new claim on the word, noting, “To me dyke is positive; it means a strong, independent Lesbian who can take care of herself.” The phrase Dykes on Bikes was coined in 1976 ahead of the first San Francisco Pride Parade, and the event has since become a staple during Pride celebrations. The first Dyke March was held in 1993 in Washington D.C., and similar events have been organized around the world since then. Importantly, NYC’s Dyke March remains an unsanctioned event, which emphasizes the radical ancestry of the march. The Lesbian Avengers, the group behind the first Dyke March, were very clear about their intentions for the event and the language behind it. Their “Dyke Manifesto” reads: “It’s time to seize the power of dyke love, dyke vision, dyke anger, dyke intelligence, and dyke strategy.”

Contemporary usage of the term has been curtailed by social media censorship. The folks behind the many lesbian meme accounts on Instagram can tell you that posts containing the word “dyke” are often removed from the site because the word is seen as hate speech regardless of the situation. Because social media tends to flatten context, “dyke” finds itself at the whims of censorship and misreading when deployed online.

When I asked survey respondents to define “dyke,” answers ranged from practical to poetic. Descriptive phrases included “irreverent,” middle finger,” “declarative,” “political,” and “self-possessed.” One participant noted the connection to masculinity, while another described it as “a kind of radical abjection from womanhood.” As for personal usage, at least one respondent commented that they do not use it because it still feels derogatory to them in every context.

One person noted that they don’t use it because they “haven’t lived the dyke experience,” while others mentioned that they are hesitant to claim it because they are femmes or not butch. Several mentioned that the word’s purportedly threatening aura is actually empowering or freeing. One individual wrote that it is useful in terms of the solidarity it creates and someone else highlighted the sense of history and community contained within the term.

Evidently, the meaning of queer language changes significantly based on time and place. Online discourse about these terms can get downright nasty, particularly when one person’s definition of a term clashes with someone else's. Indeed, the fact that these words are not just descriptive but also defined by a personal sense of identity and community means that the baggage they carry is quite hefty. There is a sense among some lesbians that our language or culture is disappearing. This is not an unfounded assumption considering the much-publicized closure of lesbian bars across the country and the relative absence of the term lesbian within popular media. It’s likely that this sense of loss has fueled much of the debate around how we define words like lesbian or queer.

If we take a step back, we’re able to see the bigger picture, which is that lesbians and queer folks more broadly have always been inventive with how they use language and build community. Identity terms like these have multiple functions, from personal empowerment, to community relations, to historical remembrance. Language can be used to build people up but also to tear them down, and we have always had the power to define our own dialectical destinies. Moreover, having a holistic understanding of our histories and our broader community – how we spoke, lived, and loved – can enliven our visions of the future. Language and identity are sticky subjects, but underneath that stickiness, there are some words worth fighting for.

Very interesting. Thank you. I spent a couple years in therapy in the 1970s claiming the title “dyke.” I still use both lesbian and dyke to describe myself. I have difficulty calling myself queer--too much hatred when I was coming out--but will use it to refer to the community. It’s much better than the ever-growing alphabet. WLW always seems to me that it doesn’t necessarily include sexuality. I’ve known a lot of WLW who didn’t have sex with each other. Great article.

Can I like this twice??

As always, your study of language and culture is enlightening. Fantastic work. What stands out for me is the reveal (not only to ourselves, but others) that we’re a community of diverse opinions and not everyone has the same relationship to the words we use or agrees on what they mean. There’s also generational components so that some terms may never reach some individuals positively.