What Even is Queerbaiting?

On Billie Eilish, Rizzoli & Isles, and the Legacy of Xena

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe!

If you read this newsletter religiously, or, if like me, you spend way too much time on Twitter, you may recall that last month Billie Eilish was accused of queerbaiting following the release of her Lost Cause music video and an accompanying Instagram caption that read “i love girls.” Fans thought that the video (which features Eilish and several scantily-clad women in a sleepover-like situation) and the Instagram caption were either a means of attracting queer viewers (without Eilish actually being queer herself) or a way for Eilish to implicitly come out. (Eilish currently has a boyfriend). The discussion was reignited when, just this week, Rolling Stone published an article titled Why Queerbaiting Matters More Than Ever which makes references to Eilish and several other purported celebrity examples of queerbaiting.

I initially was (and remain) somewhat skeptical of how the term “queerbaiting” was used in that context, but instead of diving right into that specific example, I want to first get a handle on the context of the term and how it’s been used historically. In general, I find that the term queerbaiting is often at risk of being, if not misappropriated, at least deployed without a clear definition in place. At the very least, doing some definitional work and thinking about how it has been used in the past might help us better understand the current discourse.

As a term primarily used among digital fan communities, the word queerbaiting has been in use for at least a decade, with scholars only engaging with it as a phenomenon worth studying in the last five years or so. Judith Fathallah, one of the first scholars to take queerbaiting as a serious object of study, defines the term as such: “A strategy by which writers and networks attempt to gain the attention of queer viewers via hints, jokes, gestures, and symbolism suggesting a queer relationship between two characters, and then emphatically denying and laughing off the possibility.”

Fathallah’s definition gets at what I think are the most central characteristics of queerbaiting, and also gives you a sense of the context of its use. Several things are important to note here: One, the idea of producers specifically trying to attract queer viewers, and two, the notion of laughing off the possibility of queerness when confronted with it. These two characteristics paint a clear picture of how queerbaiting has come to be defined, ie. that it is a conscious effort with often deleterious effects on queer fans themselves.

Secondly, it is clear from this definition that queerbaiting has primarily (though not wholly) been used to describe actions that occur within the realm of television, film, or other scripted forms of media. Again, a large part of what makes queer fans feel hurt by the practice is the idea that they have been led on by writers or producers, people who have full control over where a story goes and choose to dismissively deny queerness at every turn.

Certainly, because queerbaiting is a term that emerged in quick-moving online fan spaces, it has been used to describe phenomena that don’t quite fit Fathallah’s definition. What is important to a contemporary understanding of queerbaiting is the context in which it is used. As scholar Emma Nordin writes, “Queerbaiting is a historical[ly] situated term, assuming that we live in a time and place where queer representation is possible yet constantly denied.” This historical piece is significant, as is the assumption that we are now living in a time where queer representation can occur without as much pushback as in earlier eras.

A great example of this historical context is the classic (lesbian) fantasy show Xena: Warrior Princess. Were Xena produced contemporarily, it would have almost surely been accused of queerbaiting. (And indeed it still sometimes is). But, because the show aired in the 1990s, the queer subtext (which was at times very nearly text) that was present in the show was instead seen as a strategy to include a sapphic narrative without making it explicit, a move that would have put the series in danger of being canceled. Indeed, the creators and stars of Xena have stated that they knew how queer fans perceived the lead characters and consciously leaned into these queer readings, pushing the queerness of the show as far as the network would allow.

Similarly, one of the biggest criticisms of the term queerbaiting is that it is often used to describe things that are simply subtext, not queerbaiting. As Monique Franklin puts it in the collection Queerbaiting and Fandom, “subtext is framed solely as a means of withholding representation,” and thus fans who enjoy subtext or have “queer readings” of media are seen as masochistic. Subtext, of course, can be a very rewarding narrative strategy. Think of Mulder and Scully on The X-Files, or Booth and Bones on Bones, both of whom were arguably at their most interesting before they canonically became a couple.

However, the difference between couples like those and characters read or coded as queer is that the subtext between straight couples is almost universally understood and read as romantic and/or sexual. Even before the relationship becomes canon, if it ever does, the potential (or even the perceived off-screen reality) is an acknowledged fact by many viewers. On the other hand, when you look at a show like Rizzoli & Isles, which has almost the exact same format as shows like The X-Files and Bones (down to the witty banter between an enterprising cop and an overly logical doctor), the subtext is emphatically denied by the show’s creators and other (non-queer) fans.

Post-Xena, there are numerous examples of shows and films that fit Fathallah’s definition of queerbaiting. In my opinion, one of the most egregious instances occurred on the aforementioned crime drama Rizzoli & Isles. In addition to the fact that, as I said, Rizzoli & Isles has the exact same format as other detective shows where the two leads almost always have some sort of sexual chemistry, writers were aware of and at times winked at (or baited) their queer audience. Series creator Janet Tamaro once said “the lesbian theory endlessly amuses me, and it amuses the cast. Rizzoli and Isles have been heterosexual from the first episode,” despite a Season 4 promo that narrates how “the attraction is undeniable” and an episode very subtly titled “I Kissed a Girl.” Series star Angie Harmon (the titular Rizzoli) in fact once said “sometimes we’ll do a take for that demo” in a 2013 interview with TV Guide. Various promotional materials often played up the two women’s chemistry despite writers staunchly denying the possibility of a romantic arc for them.

Then there was the (in)famous controversy surrounding the Pitch Perfect films. Upon the release of the first film in the franchise, fans were immediately drawn to the relationship between Becca and Chloe (known as “Bechloe”). Their relationship was never made canon, but a trailer for the third film indicated the possibility of a kiss between them, and it was confirmed that such a kiss scene had indeed been filmed but did not make the final cut. Bechloe fans were understandably upset by this and felt they were baited into something that was never actually going to happen. There was even a change.org “Petition for the Bechloe kiss to be released,” which currently has nearly 9,000 signatures. (There is a grainy video of the famous kiss on YouTube).

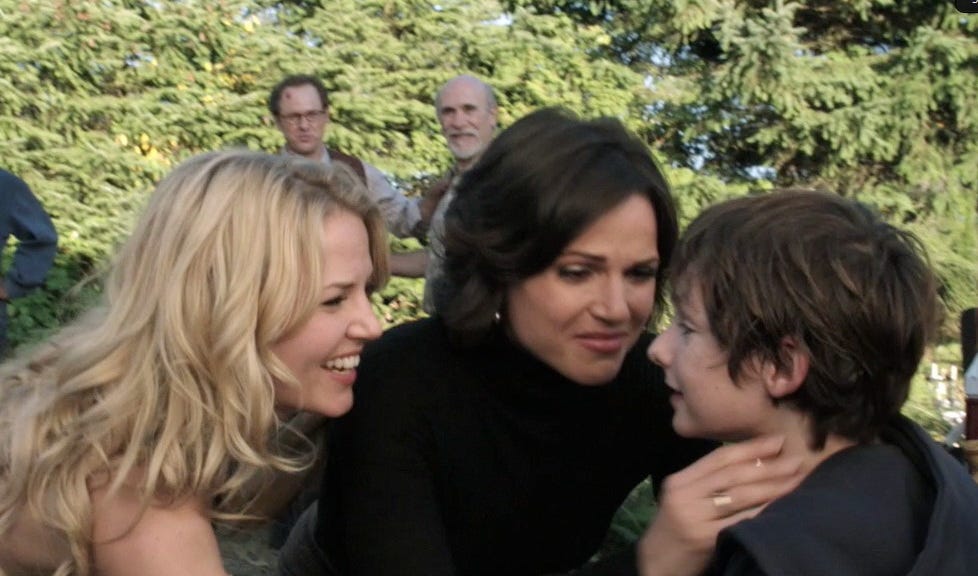

Other popular examples of queerbaiting include Once Upon a Time (specifically the Swan Queen relationship), Supernatural, and Sherlock, the latter of which was the subject of Fathallah’s original article about queerbaiting. All of these follow the same formula of creators or cast who seem to be aware of the queer implications of the text and encourage queer readings, yet deny – oftentimes in a dismissive manner – canonical queerness. (Castiel was technically made canonically queer at the end of Supernatural, but the conclusion of his arc was less than satisfying).

One particularly scandalous example of such a dismissal occurred at Comic-Con when the cast of Supergirl repeatedly joked and sang about how a popular sapphic ship – SuperCorp – would never get together, seeming to suggest that the very thought of it was ludicrous. Many fans were deeply hurt by this, and it is a perfect example of “laughing off the possibility” of queerness, as Fathallah puts it.

Of course, there have always been debates about the term queerbaiting, as those who use it surely don’t all have the same definition in mind nor do all viewers interpret media in the same way. While the term is mainly used to describe fictionalized media properties, it has at times been used to describe real people (such as Eilish), most notably Nick Jonas, who was accused of queerbaiting around the same time he started taking lots of shirtless selfies and playing gay roles on television. (Not to mention the time he gave a weird speech at the Pulse vigil).

Frequently I find that the term is used without much context or definition, such as in this Autostraddle list Top 25 Most Egregious Acts of Queerbaiting on TV, which includes everyone from Xena and Gabrielle to Eve and Villanelle from Killing Eve. (Now I know this list was written at least partially in jest, but Eve and Villanelle canonically want to both murder and have sex with each other, so I’m not really sure what we’re talking about here).

Nonetheless, I understand everyone is coming from a different place in regards to their own personal history of media consumption, and I know that sometimes this place can be an emotional one. As Evangaline Aguas writes in Queerbating and Fandom,

“As the fans’ interpretive strategies fluctuate between a lingering injury and a playful optimism, I see a disruption of the linearity of past-present-future and a warping of time. For these queer fans, the pain and wounds of queer – and screen – history are ever-present, advising caution in their emotional investments [emphasis mine].”

For those critical of the term and its varied use (which I myself sometimes am), this, I think, is an important piece of context that might allow us to be more sympathetic to calls of queerbaiting, even when they seem to come out of left field.

Indeed, one feature of queerbaiting that might be missed within a more intellectual or analytical discussion of the term is the part where feelings come in. I’ve never watched Once Upon a Time so I can’t speak to that context specifically, but what I do know is that Swan Queen fans often felt hurt or mistreated by the show’s creators and cast, as well as by other fans. I did watch Rizzoli & Isles, so I can speak to the feelings that show brought up, namely the frustration that comes from waiting for something that you know will never happen and being made to feel delusional for wanting it in the first place. (Unsurprisingly, shows like these often produce the most prolific fan creations such as fan fiction and fan videos, precisely because the shows themselves can be so frustrating).

Again, I think part of the reason why these conversations can be confusing and sometimes lack nuance is that queer-adjacent media can bring up a lot of emotion in viewers, and this emotion can sometimes trigger defensive, injured responses. I don’t mean to say that all accusations of queerbaiting are wrong or illogical, but rather want to point out the context in which they are lobbied. Indeed, to be a seeker of queer media – particularly if you’ve been seeking for the last decade or so – is to be continuously disappointed.

Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean words should cease to have meaning. Part of having media literacy is understanding the context of cultural productions, and being able to both think critically about what messages are being broadcast while also leaving space for ambiguity and multiplicity.

While I think queerbaiting can be a useful term when applied to fictional, scripted media, I admit I am slightly troubled by the implication that an individual can queerbait with something as innocuous as an Instagram caption. To be sure, celebrity PR is a business like any other in Hollywood, and I am not suggesting celebrity personas aren’t ever molded to create a more lucrative brand or appeal to various demographics. What I am suggesting is that I find it disconcerting that celebrities – especially young ones like Eilish – aren’t being given the space to be somewhat ambiguous with their sexuality or gender presentation without making a definitive statement about it. Indeed, part of the controversy seems to stem from the idea that musicians and other artists owe us every detail about their personal lives, and that their art does (or should) always reflect their interior selves.

Frankly, I also wonder if we can continue to enjoy queer readings and subtext without so explicitly tying it to the intentions of creators. I did find Eilish’s video for Lost Cause to be pretty gay, but I also didn’t consider it to be a reflection of her sexual preference, nor do I necessarily know or think that Eilish ‘meant it’ that way. It’s a far cry from t.A.T.u.’s All The Things She Said or Katy Perry’s I Kissed A Girl – but then again, it is a different time, and people have different expectations (and rightly so). And, in truth, it probably makes more sense to categorize something like “I Kissed A Girl” as fetishization rather than queerbaiting, delivered as it was with a hypersexualized wink rather than as an autobiographical anecdote.

Once again, we are lead back to another complication of queerbaiting as a descriptive or analytical term – it can be difficult to parse out the intention behind a piece of media, and that has always been an important characteristic of queerbaiting as a cultural phenomenon. That is why it is a term most usefully applied to fictional pieces of media, stories that can be made to string us along or give us narrative closure depending on the will of writers. I wonder if there is a happy medium we can find, somewhere between holding creators accountable for their actions and the content they create while also allowing space for interpretation and subtext. If not, I fear the term might start to lose its diagnostic bite.

Thanks for subscribing to Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you liked this, feel free to share it.