The Trap of “Good” Representation

On Lesbian Ghosts and the Muddy Politics of Representation

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. Plus, stay tuned for this week’s dispatch from the lesbian internet. If you like this sort of thing, subscribe!

This past fall, the show that has captured the attention of sapphics everywhere is the Netflix series The Haunting of Bly Manor, creator Mike Flannigan’s follow up to his successful series The Haunting of Hill House. Though it doesn’t become clear until at least halfway through the season, the central love story of the series is a relationship between two women, Dani and Jamie. Unspursingply, this relationship captured the hearts of lesbians and queer women and has been the talk of the sapphic town since it premiered in October. Though it has received generally good press for its lesbian representation – despite its (spoiler) very tragic ending – at least one reviewer has deemed the relationship an example of “negative” queer representation.

In a much-maligned article published in Indiewire several months ago, one critic took offense at numerous aspects of the story, including, among other things, that the series is yet another example of the Bury Your Gays Trope and that the lesbians characters are “not queer enough” to be celebrated as good representation. The author in particular takes issue with the lack of sex depicted between the two women, noting that Theo Crane in The Haunting of Hill House was more explicitly sexual, thus making her character a step forward for lesbian representation rather than a step back. (For the record, I don’t think the plot of either show fully holds up under scrutiny).

The impracticality of these arguments aside, such claims underscore a recent shift in how we talk about the representation we see on screen. There seems to be an increasingly popular belief that there is such a thing that can be decisively called “good” or “bad” representation, and that we can make these categorizations easily and without contradiction. As it stands, distinctions like “good” or “bad” when referring to a term as vague as representation only serve to obscure the larger cultural and artistic nuances of a piece of media. What does “good” (or bad) representation even look like?

That’s not to say we shouldn’t critique, or alternatively, celebrate the ways in which media represents certain communities or people. The particulars of representation are significant, particularly as they align with or depart from commonly held stereotypes that do have “real-life” effects. But this focus on the elision of stereotypes and the purported standards of representation need not obscure the multivalent meanings that a piece of art may have, both to individuals and to culture at large. Indeed, a particular aspect of a series or film might be considered “good” and another “bad,” and the same show might feel like positive representation to one viewer and negative to another. Without giving these terms real definitions or placing them within a larger socio-historical context, the discourse about representation becomes one-dimensional.

Critiques of pop culture at the level of identity and symbolism can and have been done well by many cultural critics. See, for example, Shannon Keating’s brilliant critique of the way Bly Manor relies on lazy tropes of monstrous mothers and female sacrifice to tell its story. Rather than falling back on easy classifications like whether or not the characters represent queerness “well,” Keating’s substantive analysis instead focuses on the recurring themes of the series and the messages we are left with when we look beneath the surface of identity markers.

Indeed, one of the issues with such a focus on superficial representation is that this discourse is primarily concerned with aesthetics rather than substance. This is especially true in regards to lesbian pop culture, which is often associated (perhaps unfairly) with normative aesthetics of beauty rather than exciting or unique storytelling. (Look no further than the pop-cultural obsession with lesbian period pieces). Rather than considering who or what we are seeing on screen, why not ask questions like what does this mean? Or what is being said here?

When we get stuck at the level of the visual or the aesthetic, we begin to miss the effect (or the lack of effect) that media can have at the level of the material. This is particularly true now that this mantra of “representation matters” has been applied to politics, an arena in which one would hope policy and material change would take precedence over symbolism. Take for example the election of Vice President Kamala Harris, the first woman and the first person of color to be elected to the office. Harris’ candidacy and eventual election was celebrated by many as a historic moment for black women, Asian women, and women of color everywhere, while others critiqued her troubling history as a prosecutor and her role in criminalizing black women, particularly trans black women, sex workers, and working-class mothers. When we consider Harris’ election only at the level of the visual or the symbolic, we miss the broader context of her place within American politics and the material consequences of her political career.

While of course the material effects of the actions of a prosecutor or vice president are far graver than that of a television show, the impulse to celebrate or critique on the basis of aesthetic elements now runs through both pop culture and politics. Indeed, one of the most strenuously oversimplified aspects of today’s representation discourse is the notion that one can define a person or a piece of media’s entire symbolic meaning or intention based on a set of identity factors. A piece of media is not automatically feminist because it portrays or was made by women, nor is someone necessarily pro-black or pro-queer because they fall into one of those categories. These easy categorizations are first of all difficult to decisively make, and also simplify a complex set of social and political relationships. Asking questions like Is Wonder Woman a Feminist Movie? not only obscures and oversimplifies the definition(s) of feminism (of which there are many(, but can’t, or perhaps shouldn't, be decisively answered one way or the other.

In a similar vein, asking if something is “good” or “bad” representation is an oversimplification of the complex structures of media production and reception. For whom is this representation good for? What do we find when we peel back the veil of aesthetics? Can something be both good and bad representation at the same time? A binary understanding of representation only serves to conceal the complexity of popular culture, in regards to both the texts themselves and how they are perceived by audiences.

At a time in which our lives are so saturated by media, it’s important that we are able to engage critically with the messages we receive on a daily basis. While pop-cultural literacy might not seem like the most essential skill, it would be a mistake to think that pop culture and politics are not connected. As such, these simple binaries will no longer do. If a new framework for understanding pop culture is to emerge, it must be able to balance, rather than submerge such complexities. Representation has not stopped mattering, but it’s time to reach beneath the surface.

Welcome to this week’s dispatch from the lesbian internet.

Apart from that one national event that apparently transpired on Wednesday, the most important occurrence of the past week is that child entertainer JoJo Siwa has come out as gay. The first “hint” came on TikTok, where on Thursday she posted a video of herself mouthing the words to Lady GaGa’s Born This Way. Many took this video as JoJo’s way of coming out, but this assumption wasn’t confirmed until Friday when she posted a photo of her wearing a shirt that reads “Best. Gay. Cousin. Ever.” which she says was a gift from her cousin. Then, on Saturday she did an Instagram live (wearing a rainbow bow of course) wherein she thanked her fans for the support she received following her coming out, explaining that’s she’s never been this happy in her personal life before.

Now, I will do my best to give a little background on JoJo Siwa, but I’m not sure I fully comprehend the enormity of her star power myself. Essentially, Siwa, who is now 17, first rose to fame after her appearance on the Lifetime series Dance Moms, and then released her debut single Boomerang several years later at the age of 13. Since then, Siwa has amassed a huge following among young girls, has a YouTube channel with more than 12 million subscribers, and has become particularly known for the oversized bows she wears on her head (pictured above).

Essentially, Siwa coming out is a huge deal because her fans are primarily children, and we all know how puritanical some parents can be about the type of content their kids consume. Despite the perpetual youthfulness of her image, Siwa (or at least her “team”) surely must have known the blowback this could have on her career, and the fact that she came out with all the exaggerated cheerfulness she is known for makes it all the more iconic. Regardless of whether or not this announcement affects her popularity among children, she now has a legion of adult queers on her side. (In other news, I now follow her on Instagram).

The next most important thing that happened this week involved Dakota Johnson. First, shocking the whole nation, Johnson revealed on Jimmy Fallon that her infamous love of limes (as seen in her iconic Architectural Digest video) was a lie, and that she is actually allergic to limes and they were put in her house as set dressing. I can’t fully get into the internet’s love for Dakota Johnson right now (see Iana Murray’s article on the subject), but her AD video and her famous confrontation with Ellen about her birthday party are what have endeared her most to the public recently, so the fact that she lied about loving limes feels like a deep betrayal. (If we don’t have Dakota Johnson and her limes, what do what have???)

Luckily, another bit of Dakota Johnson news has come out this week, and that is the fact that she is playing a lesbian in an upcoming film directed by iconic Hollywood couple Tig Notaro and Stephanie Allynne. (Who, by the way, have one of my favorite relationship stories ever). Now, this does not totally make up for the lime betrayal, but it’s a start.

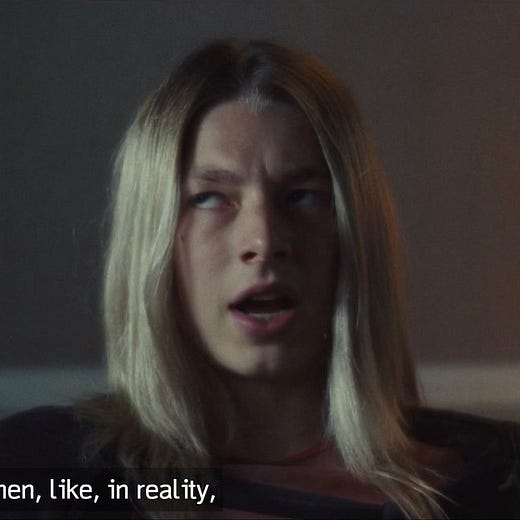

Lastly, the second Euphoria special came out on Friday, this time following Hunter Schafer’s Jules (the first special starred the incandescent Zendaya). Unfortunately for the state of all of our mental health, the episode opened with Lorde’s Liability, which was an emotional gut-punch when it was first released and continues to be so in the context of sapphic heartbreak and the general milieu of 2021.

Luckily the episode also included a brilliant performance by the incredible Hunter Schafer, who also co-wrote the episode with showrunner Sam Levinson. In a stunning monologue partway through the special, Jules ruminates to her therapist about how she has constructed her femininity based on what she thinks men want (pictured above). To me, this episode proved that it’s Schafer’s genius that should be celebrated here rather than Levinson’s, as her brilliance as both a performer and a writer were so clearly displayed here, and the episode in no way could have gone to the depths it did without Schafe’’s contribution. Anyways, Hunter Schafer is everything, and trans femmes are the future.

That’s all for this week, folks! I will leave you with this: