This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including February’s monthly playlist.

Tragedy is one of the oldest recognized genres of art. More specifically, it’s considered a classical art form, and is closely associated with the playwrights of Ancient Greece. Within philosophy, there are several different arguments about the function of tragedy as a creative force. The most famous theorist of tragedy is Aristotle, who argued that tragedy is both artistically and morally useful. Aristotle maintained that tragedy has an important function in society in that it can produce a sense of catharsis in audiences, “through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions.”

One of the other great philosophers of the period, Socrates, disagreed with Aristotle about the necessity of tragedy, suggesting that tragedy was in fact immoralizing because it leaves audiences discouraged by the state of the world and thus less likely to carry on being moral citizens. Nietzsche, a famous nihilist, took an entirely different approach to the question. He believed that tragedy was neither moral nor immoral, but could be useful because it relieves the audience of the burden of knowledge about the world’s suffering. As Christopher C. Raymond writes, Nietzsche thought that “ tragedy is meant for those (like himself) who have already seen through this illusion.”

When it comes to lesbian and queer art, tragedy is a hotly debated topic. In many ways, such debates align with the fundamental disagreement between Aristotle and Socrates. A common refrain today is the idea that there should be no more tragic lesbian movies made, because there have already been so many in the past that, as a whole, have had a demoralizing effect on the community. But, culturally speaking, the connection between lesbianism and tragedy isn’t so straightforward.

Scholar Heather K. Love writes brilliantly about the film Mulholland Drive, honing in on the concept of the tragic lesbian as a thematic focal point. Importantly, Mulholland Drive depicts tragedy in its modern form. What’s significant about tragedy in the contemporary era is that our time is defined by the drive to eliminate tragedy, all the while recognizing that tragedy is more diffused and universal than ever. The democratization of tragedy means that everything is tragic, which also means that tragedy is no longer exceptional or a position from which one can organize.

For those considered minorities, there is an expectation of tragedy that therefore does not compute as genuinely tragic. Love writes that lesbian suffering “does not really register as tragic, but as simply sad or pathetic.” This is because queerness is already defined as a socially impossible position. “Given that homosexuality is considered a tragic state of being, it is difficult for any individual homosexual life-story to signify as tragic,” Love writes. But this means it's all the more important to name tragedy as such, even if it appears somehow morally destructive. Indeed, Love notes that so-called positive thinking and positive art do not go deep enough into the pain of dispossession, and that tragic art is not simply a regressive form. She maintains that “we need a politics that goes “all the way down,” that is attentive to the dark places of affective and erotic life.” Modern tragedy may be difficult to observe, but it can helpfully illuminate the structural barriers of contemporary life.

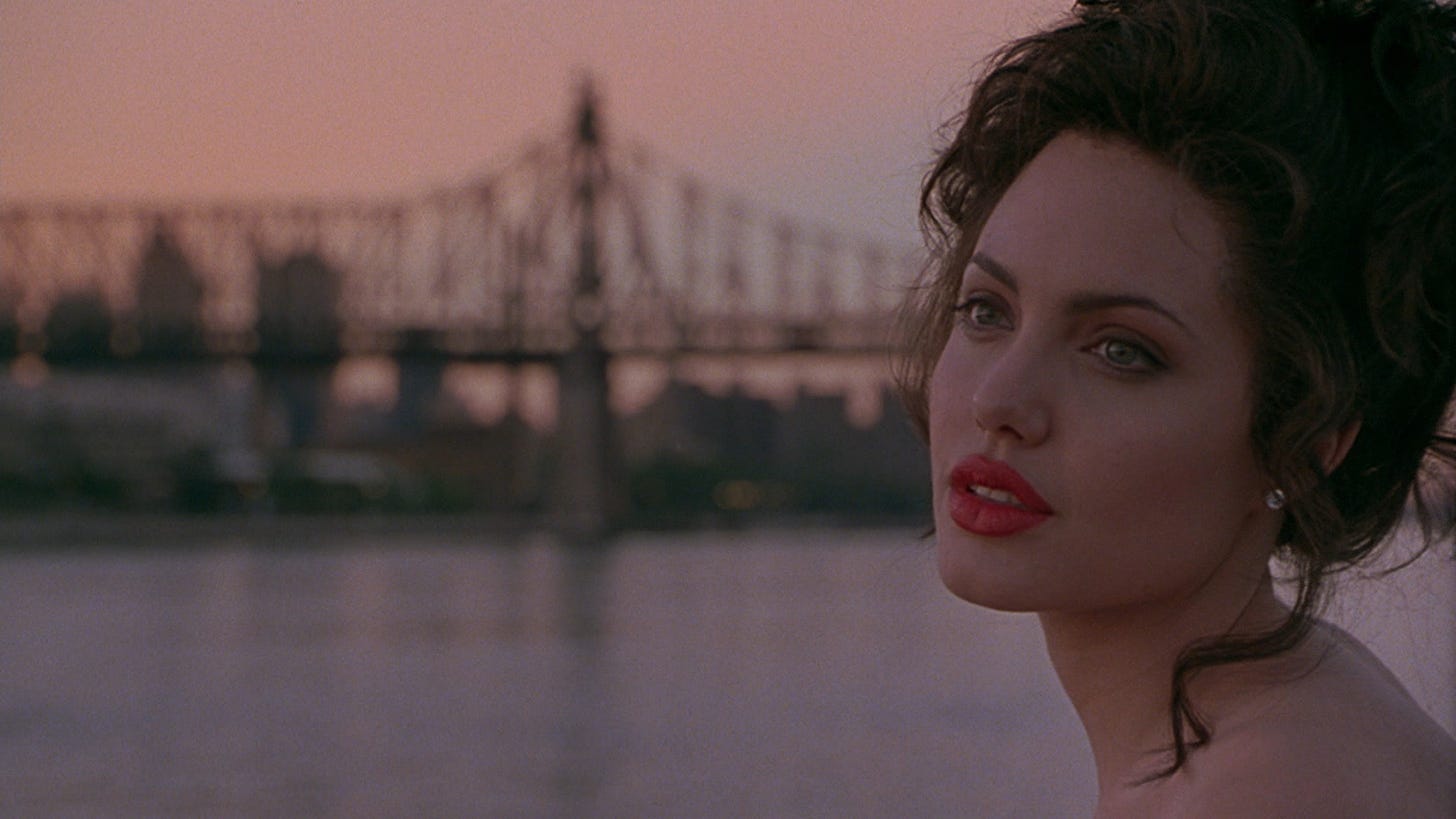

There are dozens of films that could be described as lesbian tragedies, and the one I’m thinking of is a tragedy of the highest order. Gia is a 1998 HBO film starring Angelina Jolie as the titular character, Gia Carangi. Born in 1960, Gia was an American woman often considered to be the world’s first supermodel. Importantly, Gia died from AIDS in 1986 and was the first well-known woman to die from the disease. She’s known as much for her beauty and androgynous style as she is for her queerness, and has since become something of a lesbian icon.

The film is a biopic of Carangi filmed in a sort of faux-documentary style, with talking heads describing Gia throughout. It purports to be highly artistic, but it is also very obviously a made-for-TV movie from the ‘90s, a format that didn’t have the connotations of quality it does today. (This also meant that Jolie and the rest of the cast and crew weren’t eligible for any Oscars.) Some of the aesthetic choices in the film are rather bothersome, especially the constant shifting from color to black and white, a technique presumably meant to highlight the importance of photography in the story. The film’s score is composed mostly of sensual jazz music, another choice that ties to the film’s austere ambitions. These visual and aural cues are meant to highlight the seriousness of the film and the subject at hand – a seriousness that correlates with the overall timbre of tragedy. This right here is important, these aesthetics seem to say.

In many ways, Gia is pre-figured as a tragic character, something Love underlines in her discussion of the concept. For one thing, Gia is very clearly portrayed as queer from the moment we first see her, with spiky pink hair and Jolie’s own dragon tattoo on her arm. The first friend she meets in the film, T.J. (Erich Michael Cole), would presumably like to have sex with her, but she constantly turns him down, stomping around in his tighty-whities instead. (Later, she makes out with T.J. and a photographer and then has them make out with each other while she walks away.) She describes having sex with a man by saying “I could have done that with a german shepherd.” Then, of course, there’s her life-altering relationship with Linda, which we’ll get to in a moment.

The faux-documentary portions of the film depict those who knew her talking about what kind of person she was. Some of her former “friends” and colleagues describe how rowdy she was and how she always followed her instincts, no matter where they led her. “Too beautiful to die. Too wild to live,” reads the film’s tagline. It’s a laughably reductive statement, and one that is simultaneously upheld and refuted by the film itself. From the very beginning, Gia is very aware of how she’s seen by others, but the film constantly reminds us that she’s an enigma and was perhaps never fully known by anyone. This mystery adds to the legend the film builds about her, as well as deepening the sweeping tragedy of her life.

Love makes the distinction between something being pathetic and tragic, noting that if the lesbian is an abject figure, she can’t also be constituted as tragic. In order for something to be meaningfully tragic, you must first care. With its conspicuous air of seriousness, the film is often moments away from falling into pure melodrama, which would seem to contradict its lofty artistic aspirations. But the film registers as both tragic and worthy of serious consideration primarily because of Jolie’s riveting performance. She imbues Gia with a vulnerable ferocity that allows the audience to understand that her downfall is not a foregone conclusion. Jolie’s work here defies the sort of pre-figured queer tragedy of which Love speaks, her vivacity constantly pushing up against whatever reductive stories are being told about her – even the ones told by the film itself. Despite her purported wildness, this Gia is so open-hearted and exposed that you want her so badly to succeed and get better, though you know this will never happen. Hence, tragedy.

Jolie’s incredible performance may be the glue that keeps the film from falling apart, but Gia’s relationship with makeup artist Linda, played by Elizabeth Mitchell, is the film’s emotional core. (Faye Dunaway as Wilhelmina Cooper, Gia’s mother figure, is also essential.) While Gia is restless and spontaneous, Linda is soft and grounded. Mitchell’s delicate, lilting voice sounds even more lovely when in conversation with Jolie’s frenetic energy. Jolie and Mitchell have warm, almost innocent chemistry that grounds the film’s more ponderous elements. Quoting David Bowie, one of Gia’s heroes, she tells Linda, “I will be king, and you will be queen.” Gia’s a romantic, but she’s also portrayed as childlike and in need of love. In her talking head interview, Linda describes Gia as a puppy vying for attention. Gia and Linda have a passionate, loving relationship, which, of course, doesn’t last forever. But the notion that Gia did have a great love in her life serves to make her death even more devastating to confront.

As Gia struggles with drug addiction and tries and fails several times to get clean – mostly for Linda’s sake – the tragedy of it all is forcefully emphasized. The moment when she uses a needle for the first time is treated with the utmost importance, and it clearly (and perhaps a little too obviously) signals the beginning of the end. The dichotomy between excess and ruination is emphasized most clearly during a scene where Gia walks away from a crying Linda and directly onto a gleaming runway, though she can only escape her worries for a moment. It’s a very conventional framework about the downfall of fame, but it is effective despite its bluntness.

Things get worse from here. Gia calls Linda from rehab and apologizes, and it breaks your heart right open. Later, Gia tells her mom “I don’t feel so good” and collapses in the kitchen. But there’s nothing more devastating than Gia and Linda’s final moments together. Now fully aware that she’s dying, Gia goes to visit Linda but doesn’t reveal the truth of her condition. “We have all the time in the world,” Linda tells her, in a painful twist of dramatic irony. Gia leaves Linda with a parting gift, telling her “You were the one. You were the only one. And you are amazing.” And then it’s all over.

In many ways, Gia’s story is very familiar. She’s a shining star who rose to fame only to be taken from us too soon, often understood to be a victim of her own ferocious lust for life. But as a tragic lesbian figure – and indeed, this is how the film frames her – her story is more complex than that. Love writes that it is difficult for queer individuals to be figured as dramatically, seriously tragic because they are pre-constituted as already-tragic. The film contends that while her story may be familiar, Gia is also wholly unique and maybe even unrepresentable, despite the fact that she is the subject of the picture. Certainly, Gia’s queerness figures into her tragedy, but it's also her lesbian love story that makes the tale worth telling. This, in a sense, also makes her more knowable.

Love writes about the taboo of masochistic lesbian fantasies, “fantasies about lesbian abjection and glittering femmes fatales.” As in Mulholland Drive, Gia represents both ends of the spectrum. Her simultaneously abject state – for nothing is more abject than an AIDS patient – and her glamorous fame are ideologically rich contradictions, and they ask us to consider tragedy from several different vantage points. Gia may not be an everyday example of tragedy, but the narrative of her descent illuminates the social – not natural – conditions that pre-empted her death.

These taboo stories needn’t be thrown out entirely. Gia is a modern figure of lesbian tragedy, and the film doesn’t shy away from confronting the dark places that Love urges us to discover. Gia gets knocked down time and time again, until, finally, she’s run out of second chances. This is devastating to watch, but not stultifyingly so. As Love suggests, “it is not necessary to imagine that homosexual life will never change in order to experience it as tragic in the present.” The repeated thought one has while watching Gia is “if only things were different.” While tragedy as a (queer) art form is often seen as socially regressive, this question actually has a propulsive force to it. If only, if only, if only…

This is such a brilliant essay, thank you for writing and sharing it! The line "In order for something to be meaningfully tragic, you must first care." Is still ringing in my mind.