This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe!

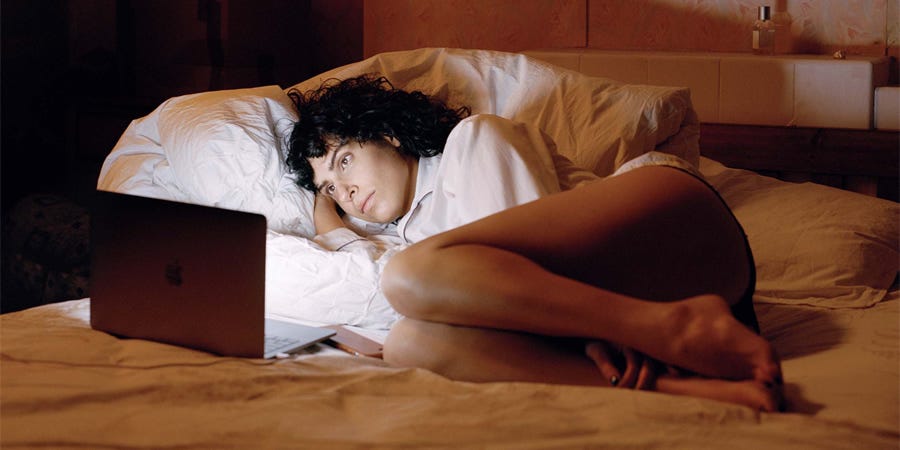

In 2018, Desiree Akhavan’s excellent series The Bisexual premiered on Hulu with regrettably little fanfare. The series focuses on Leila (Akhavan), a thirty-something woman coming out of a 10-year-long relationship and beginning to explore her bisexuality for the first time. Following its release, The Bisexual received middling reviews and certainly did not receive the accolades it deserved for the pointed interventions it made within the TV landscape.

Certainly, there have been bisexual characters on television before, but what there’s not been is a series that explores bisexuality itself, looking at it as a distinct experience with its own unique cultural connotations and struggles. According to GLAAD, the number of bisexual characters on television has been, for the most part, increasing over the last several years. Statistics aside, there are a few characters that loom large in our cultural memory about bisexuality on TV. Clarke Griffin from The 100 (now famous for burying its gays) was the first bisexual lead character on network television when the show premiered in 2014. Later that year How To Get Away With Murder premiered, and Viola Davis’ Annalise Keating became another prominent bisexual woman on TV.

One of the most impactful bisexual women on television was undoubtedly Callie Torres (Sara Ramirez) from Grey’s Anatomy, who became the longest-running queer character on network TV after she came out in 2008. (Ramirez, who is also bisexual and non-binary, has continued to play bisexual roles since they left Grey’s – on Madam Secretary and in the upcoming Sex and the City revival). Rosa on Brooklyn Nine-Nine (played by Stephanie Beatriz, also bisexual) is another fan favorite, beloved for the matter-of-fact way she goes about her life and defines her sexuality.

Overall, however, the history of bisexual representation on television has not been, shall we say, good. Many examples of bisexuality on-screen traffic in various harmful stereotypes, such as bisexuality being a joke, or not real, or bisexuals themselves being loose or slutty. Often, the idea of bisexuality is overlooked altogether. Even on a show like Orange Is the New Black, which featured numerous queer characters, the word bisexual is not used to describe lead character Piper Chapman even a single time during the show’s seven seasons. On The L Word, which featured several bisexual lead characters, bisexuality was either forgotten about or treated disparagingly by the series’ lesbian characters. Famously, Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw once described bisexuality as “a layover on the way to Gaytown.” (Cue Ramirez’s redemptive entrance in the revival).

But even in the above examples where representations of bisexuality don’t traffic in these damaging stereotypes, bisexuality itself is rarely discussed in depth. This, then, is where Akhavan’s The Bisexual comes in. Akhavan – who also directed the indie darling The Miseducation of Cameron Post – created the show as her response to being labeled as a “bisexual director,” or, even more derivatively, “the bisexual Lena Dunham,” using the series as a way to work through the feelings these labels brought up. Through The Bisexual, Akhavan was able to explore why being labeled as a bisexual provoked these feelings of discomfort and think about why bisexuality is often so hard to relate to or represent.

What The Bisexual does – quite brilliantly, I might add – is defines bisexuality as its own unique identity and experience, rather than simply something that exists under the broader umbrella of “queer.” In a way, the series reverses the coming-out story. Leila has been out as a lesbian for over a decade but then must come to terms with her identity as a bisexual, something she does with much difficulty.

Unfortunately, this novel take on sexual politics was not entirely well-received by critics. The Guardian called it “neither comic nor dramatic” and “a bleak, affectless and suffocatingly joyless affair,” and Bust wrote that it Confronts Bisexual Stereotypes At The Cost Of Characterization. In a particularly specious reading, The Hollywood Reporter suggested that “the entire conceit of a TV series debating what bisexuality even means in 2018 feels 20 years too late.” This argument falls flat when you consider that bisexuality was in fact not treated as a serious topic of discussion 20 years ago – one need only recall the famous Carrie Bradshaw quote to invalidate this assumption altogether.

Certainly, part of this criticism stems from the fact that these critics find Akhavan’s Leila to be an unforgivably unlikable and unsympathetic protagonist, messy and confused as she is. But indeed, that is also the point. If we are to take this as a coming-out story, messiness is a central conceit, and easy solutions are often nowhere to be found.

As Katherine Smith writes in Paste, Leila is not just having a singular existential breakdown, she is having overlapping ones, which make her experiences feel more realistic, and richer. What these reviewers seem to be missing is that bisexuality hasn’t been explored this way on television before, and such an examination is never going to dig up easy, digestible answers. As Smith puts it, “Bisexuality has lurked so long as a phantom in the zeitgeist—Apparently it’s everywhere! Apparently it’s nowhere to be found! But with Akhavan’s series, it’s a gentle tug, an untying of a blind fold: look there she is, the bisexual herself. Just let her be.”

As Heather Hogan suggests in Autostraddle, the point is in making the viewer feel uneasy. “She’s created a show for an audience that understands the joke “Bette is a Shane trying to be a Dana,” Hogan writes, “and then centers it on a character who’s meant to make everyone who gets that joke a little uncomfortable.” While Leila is trying to understand what her own bisexuality means to her, Hogan points out, “It’s everyone else who doesn’t know how to relate to Leila’s bisexuality, especially her lesbian friends.” While everyone is in agreement on what it means to be a lesbian, there is no such consensus about bisexuality.

Leila’s journey through bisexuality reflects her own internalized feelings about what it means to be bisexual, as well as Akhavan’s own fears about “not being gay enough.” (A particularly moving monologue in the series sees Leila wondering aloud if she would have lived her whole life as straight had she not fallen in love with a girl at age 19). Part of this, Leila realizes, is a generational struggle. While talking to her roommate’s 25-year-old girlfriend, who maintains that being queer is not a big deal, Leila explains how different their experiences seem to be.

“I think it’s different. I think when you have to fight for it, being gay can become the biggest part of you. And being gay or straight, it comes with an entirely different lifestyle, like different clothes and different friends and you can’t do both. I don’t mean to be condescending to you. I just don’t know what it’s like to grow up with the internet, but I sense that it’s changing your relationship to gender and sexuality in a really good way, but in a way that I can’t relate to.”

As Leila expresses, she feels like she’s lost her place in the world upon exploring her own bisexuality, and part of this is feeling like she’s no longer able to relate to her friends or her community. When her former partner, Sadie, sees her out with a man, she is shocked and deeply upset. “I feel like such a fucking idiot,” she says. As Sadie sees it, an experience they once both had in common – being exclusively attracted to women – is no longer (or never was) true, and this makes her feel like the rug has been pulled out from under her. In a later episode, Sadie argues that it’s worse that Leila is attracted to men in addition to women “because you can never be fully satisfied,” which of course confirms Leila’s own insecurities about bisexuality. Sadie now feels like Leila has had choices that she has never had – to live happily and settle down with a man. (This echoes Leila’s worry in Episode 2 that she could have easily not come out had her circumstances been different).

Feeling like she has nothing or no one to relate to, Leila internalizes everything she knows about bisexuality and is left with more self-hatred than acceptance. Certainly, this is also part of the objective of the show – to open up some sort of entry point for an actual dialogue about what bisexuality means to people. In a particularly harrowing monologue after her roommate suggests she might be bisexual, Leila responds:

“I don’t like that word. When you hear bisexual you think, like, Tila Tequila, you think Anne Heche.” “Who?” “Exactly. There’s nobody, there’s no precedence. When I hear bisexual I think ‘lame slut.’ It’s tacky, it’s gauche, it makes you seem disingenuous, like your genitals have no allegiance, you know? Like you have no criteria for people, it’s just an open-door policy. It’s not a nice thing to be, it’s not a cool thing to be, and it makes my fucking skin crawl.”

This is not a shallow discussion of why “representation matters,” but rather a complex dialogue about how we define ourselves in relation to others. While Leila never quite resolves her own feelings about bisexuality and what it means for her, this uncertainty is also much more true to life than most neatly wrapped up coming-out stories are. As most queer people know, you do not simply come out once and then never again – it’s an ongoing process of negotiation and acceptance that can go on indefinitely.

In creating the precedence that Leila feels so bereft of, The Bisexual opens a door to discussions that are rarely had. While nothing is really resolved for Leila and her friends, we are thankfully privy to a type of dialogue that is rarely seen on TV. In re-defining the coming-out story, Akhavan is questioning the supremacy of a particular type of narrative, one that often excludes characters like Leila. This is an intervention that is much needed in TV today, where bisexuality often exists as an unexplored given or some nebulous force, floating about in the ether. Blessedly, Akhavan brings bisexuality back down to earth.