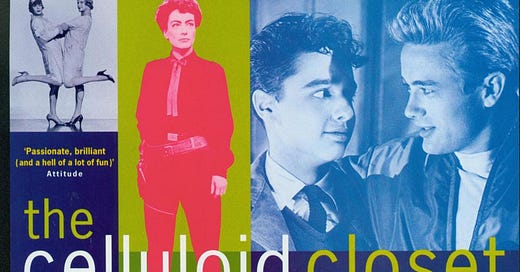

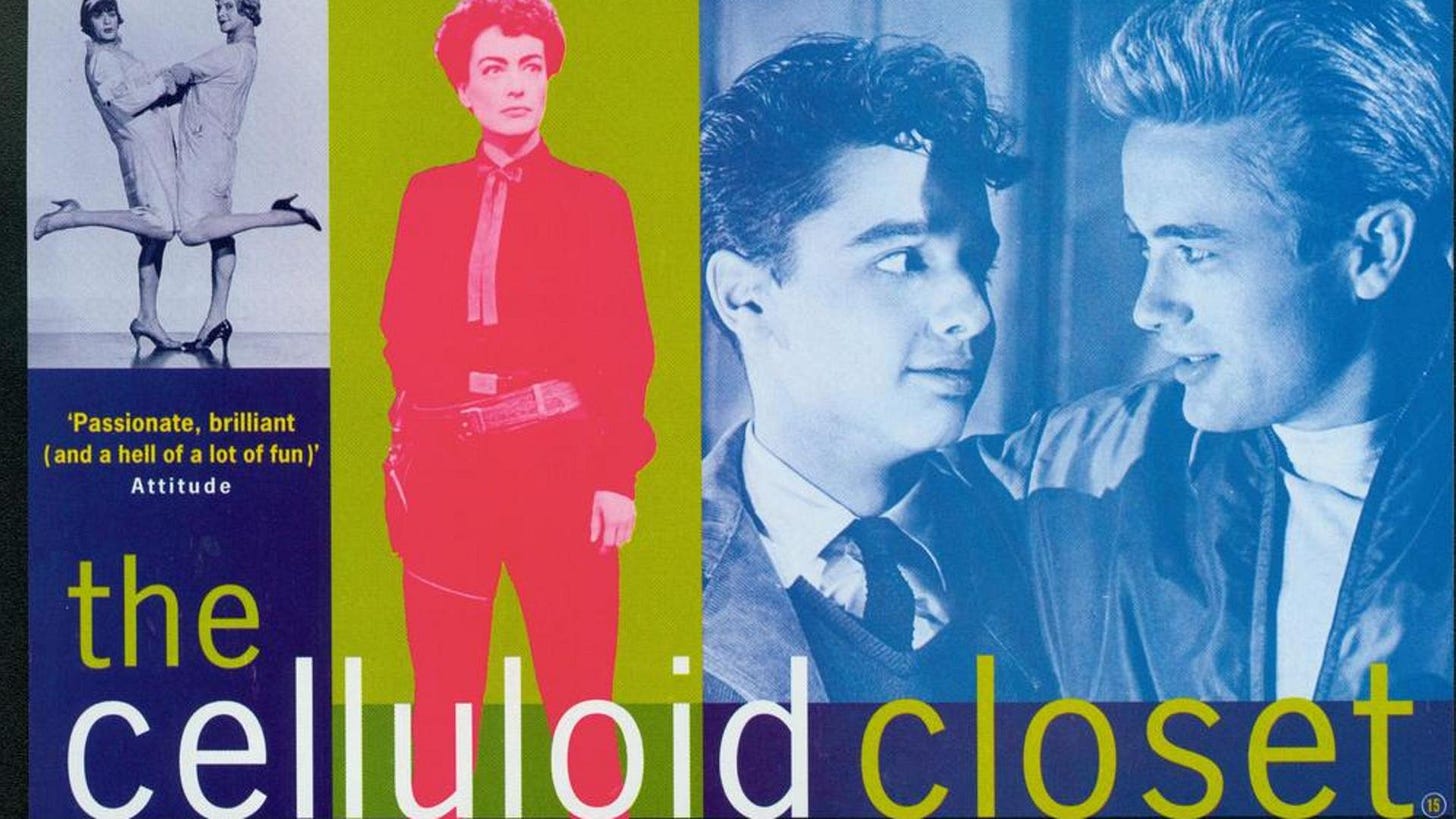

'The Celluloid Closet,' 30 Years Later

Does the groundbreaking documentary still resonate today?

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet, monthly playlists, and a free sticker.

In 1996, HBO aired a documentary called The Celluloid Closet. Based on Vito Russo’s 1981 book of the same name, the film details the history of queer representation in film up until the decade of its release. Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman directed the film following Russo’s death in 1990, using talking head interviews and dozens of film clips to paint a picture of depictions of gays and lesbians in Hollywood over time. As spoken by narrator Lily Tomlin, the film's argument goes like this: “Hollywood, that great maker of myths, taught straight people what to think. And gay people what to think about themselves. No one escaped its influence.”

The Celluloid Closet tells a story that is easy for any viewer to follow. After mostly skipping over the decades-long silent era, the film starts its history around the time of the Hays Code. Between the introduction of sound (1928) and the implementation of the Code (1934), Hollywood films started getting raunchy, pushing the boundaries of social norms. Though the Production Code – which detailed what could and couldn’t be shown on film from a moral standpoint – was published in 1930, studios didn’t start enforcing it until four years later, following pressure from the powerful Catholic group the Legion of Decency.

The experts in the film discuss the post-Code period as a time when queerness in film had to go underground. Filmmakers could sneak queer characters or themes into their films if they did it subtly enough, but censorship of any “deviance” was common during this era. As the story goes, queers didn’t disappear from the screen at this point, but rather became villains – such as The Countess in Dracula’s Daughter and Mrs. Danvers in Rebecca. For men, the “sissy” was a common gay stock character during the first few decades of Hollywood, and despite the implicit humor of these characters, the film denounces the archetype, apart from one voice that disagrees with this blanket disavowal.

Seemingly counter to the social conservatism of the decade, queerness in film persisted during the 1950s, though there was also plenty of censorship during this period. As the documentary puts it, homosexuality was discussed more openly in the next decade, but it wasn’t seen as a nice or polite topic of discussion. Many gay characters during the 1960s were terribly depressed and oftentimes suicidal.

The next chapter in this story emerged in the 1970s, when gay characters became more visible and less tragic. The consequence of this increase in visibility was further retaliation, as explicit gay bashing became more common. By the 1980s, the film contends that gay characters went from “victims to victimizers” – even though gay villains featured prominently in a previous segment.

According to The Celluloid Closet, the 1980s marked a turning point for queerness in film. The 1982 film Making Love is credited with being the first American film with a gay lead character (though Personal Best, Victor/Victoria, and Partners all came out the same year). The mid-1980s saw the first inklings of the New Queer Cinema movement, ushered in by a cadre of filmmakers that the documentary shows clips of but never discusses. Still, the conclusion takes on an optimistic tone. “The long silence is finally ending,” Tomlin announces.

At its best, The Celluloid Closet pieces together an illuminating archive of queer film history, excavating queerness where it might appear hidden. Nonetheless, the film oversimplifies much of this history and leaves out quite a bit. The documentary presents a stark dichotomy between good gay movies and bad ones, with little room for opposing opinions. It suggests another uncomplicated dichotomy – one between old films and new films. Old films are framed as repressed and oftentimes offensive, while newer films appear freer and work to improve society. This easy split overlooks the fact that many viewers in the first half of the 20th century felt a kinship to these queer-coded characters; that pop culture was a significant part of the queer community and how queer folks related to the world around them during these decades.

Indeed, one of the most vexing aspects of the film is the lack of tension within this narrative. With only a few exceptions, the experts bolster the simple story of queer progress as a linear, upward trajectory. Where others discuss how offensive the sissy character was in early films, it’s only Harvey Fierstein who dissents, noting that he always liked the sissy character in part because he is one.

Following a discussion about The Children’s Hour and all the suicidal gays of the 1960s – plus Shirley MacLaine’s admission that they “didn’t do the picture right” – writer Susie Bright wonders aloud why the film still moves her so much. She concludes that while contemporary queer culture is all about pride and celebration, many queer people still feel the shame that MacLaine’s character expresses in the film.1 This is one of the only times anyone in the film acknowledges there are more nuanced ways to discuss queer representation than simply good or bad, and why previously maligned films might offer us something useful or compelling.

Part of the issue here is that the film’s focus is too narrow. The most cohesive part of the movie is the section detailing the films of the Golden Age. During this period, Hollywood had a near-monopoly on moviemaking, meaning there were few alternative perspectives on display. (This can’t be said of later decades.) The power of such films is indisputable, though the multitude of ways these films were read remains under-analyzed.

What does this narrative leave out? For one thing, the queer creatives of the Golden Age – both in front of and behind the camera – receive almost no mention. What about Dorothy Arzner, the pioneering lesbian director who worked with the likes of Katherine Hepburn and Lucille Ball? Or George Cukor and James Whale, two of the most significant filmmakers of their era? It seems a shame to overlook the fact that so many Golden Age stars were queer themselves, such as Marlene Deitrich, Greta Garbo, and Cary Grant, and that the rumored queerness of these stars oftentimes brought gay viewers to the theaters.

Though it’s understandable considering the film’s length, foreign films get no mention either, and even British films get only a few seconds of screen time. We’re also missing any discussion of independent films, which began gaining traction in the 1950s, if not much earlier.2 There’s no mention of the legendary gay filmmaker John Waters, or other influential figures like Derek Jarman, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, or Pedro Almodóvar. There is less discussion of lesbian films than gay ones, including the omission of what is often considered the first lesbian film ever made, Mädchen in Uniform. Whoopi Goldberg, who appears briefly, is the only black expert interviewed in the film, which isn’t surprising considering that most of the films discussed exclusively star white actors.

This may seem like a long-winded laundry list of criticisms, but the concept of representation is a touchy subject that warrants careful consideration. How could a film like this be made with more nuance? What might we have to say differently if this film was made today? To answer the first question, we needn't look any further than the 2020 Netflix documentary Disclosure. The film looks at trans representation in film and television, exploring both the cultural impact of such images and the impact this media has had on individual trans folks. (This balance skews heavily to the latter consideration in The Celluloid Closet.)

The most effective aspect of the documentary is the way it allows for contradictions and differences in opinion. Indeed, these contradictions are a large part of the film’s argument – that pop culture never means just one thing. As Drew Gregory puts it in her review of Disclosure, “The movie doesn’t split representation into simple categories of good and bad, nor does it discuss intersections of race, gender, and class as mere asterisks. They are the entire point.” The linear narrative of progress depicted in The Celluloid Closet becomes far knottier in the hands of the Disclosure filmmakers and cast members.

As for the second question, there have been meaningful changes in how we discuss and view representation since 1996. For one thing, many of us have more nuanced takes on some of the films deemed controversial or negative in The Celluloid Closet. I see The Children’s Hour as an incredibly powerful and well-made piece about gay shame – rather than a harmful cautionary tale – and I’m not the only one with that opinion. Cruising, once the target of protests by gay rights groups, has now been reevaluated by some members of the queer community, and you can find it playing at arthouse theaters and festivals. The same goes for Basic Instinct, now considered a camp classic by many.

In general, audiences tend to have a more expansive view of queerness than they once did – or at least more expansive than how the documentary presents the attitude of viewers during this era. Queer audiences have always been adept at reading queerness into texts not outwardly deemed queer, and we’ve developed even more language about this practice today. (Phrases like queer coding and queerbaiting have become part of the pop-cultural lexicon.)

Still, longstanding issues of oversimplification and literalism persist. For example, the Bury Your Gays trope controversy was an important moment in the history of queer representation, as queer fans worked to hold producers responsible for perpetuating the notion that gay people don’t deserve happy endings. Years later, after the #LGBTFandDeserveBetter movement had gained traction, some viewers began taking the concept a smidge too literally. I’m thinking of this viral review of The Children’s Hour in which the viewer gave the film .5 stars because of how offensive its representation of lesbians is.

Films and their attendant meanings and social impact are not so black and white, and this includes the once-useful idea of the Bury Your Gays trope. To put it another way, it’s not inherently evil or homophobic if a gay character dies – what matters is the context in which they exist and the care (or lack thereof) the character receives.

Contemporary opinions about queerness in film have a lot to do with the broader media landscape we find ourselves in. There are significantly more queer characters and queer-themed media today than there were three decades ago. Because of this, we’re better able to accept that not every queer character has to be strictly positive or uplifting to the community. We can enjoy Basic Instinct today – previously dismissed as homophobic, biphobic trash – because it’s far from the only depiction of queerness we have at our fingertips.

Not everyone wants the same thing in terms of representation, and in fact, straightforward representation is rarely the most interesting way to describe or create a piece of media. Thankfully, some audiences have arrived at a place where they can have more nuanced conversations about these topics, though oversimplifications and demands for mural purity remain. As ever, the cultural implications of art are in the eye of the beholder.

For more on the utility of gay shame, check out Heather Love’s book Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. It’s one of my favorites.

Notably, the first independent film company was the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, which was founded – in 1916 – and run by black Americans and considered the first producer of so-called “race movies.” The company shuttered in 1923. Also around this time, the black filmmaker Oscar Michaeux began directing and producing films independently, such as 1920’s Within Our Gates and 1925’s Body and Soul. He directed more than 40 films in his career. In 1919, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, D.W. Griffiths, and Douglas Fairbanks founded United Artists to give creatives agency outside of the big studios. They are now owned by Amazon MGM Studios.

Dear Dr Lesbian, though I am glad that you devoted a whole column to The Celluloid Closet because it was and is such an important film, your critiques annoyed me at times. I think that is because, from the perspective of my 84 years, the then dominant themes in film were so overwhelmingly negative: the queer had to be a figure of fun, be scary, and/or had to die in the end. To critique those themes was so important. Obviously today, (unless we are driven back in the closet as the MAGA movement hopes), we have much more nuance to work with