This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet. This week we discussed the Met Gala and the writer’s strike.

I want to talk about bodies. Specifically, I want to talk about Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant’s bodies in Holiday (1938). George Cukor’s masterpiece is an evocative illustration of both the possibilities and the limitations of the human body. What these beautiful bodies so expressively represent is the potent contrast between rigidity and freedom. Indeed, the slyly radical film perfectly encapsulates what makes both Hepburn and Grant such compelling – and enduring – performers.

In their lifetimes, both actors – in their professional and their personal lives – found themselves pushing up against the boundaries of what was possible. Holiday exemplifies Hepburn’s enduring desire to be free, contrasting this earnest wish with Grant’s supposed embodiment of this corporeal freedom. Holiday is ostensibly a romance, but it is also a film about queer kinship and, to use a term that is perhaps unforgivably modern, found family.

Katherine Hepburn, it should be noted, is something of a queer icon. Born in 1907 to wealthy, liberal parents, Hepburn attended Bryn Mawr College before launching her acting career. Though she went on to achieve significant acclaim, Hepburn was never a conventional Hollywood starlet. Known for her fashion as much as she is for her acting, Hepburn’s dedication to wearing pants instead of skirts and dresses has remained one of the most revered aspects of her personhood. In 1981, Hepburn gave one of her most famous quotes, telling Barbara Walters “I put on pants 50 years ago and declared a sort of middle road. I have not lived as a woman. I have lived as a man." A 2016 Vanity Fair article about Hepburn continued to discuss the actress in these terms, referring to her as “gender-bending” and defining her fashion choices as “daring.”

This daring attitude emerges in Hepburn’s choice of roles as well. Her most queerly gendered role is 1935’s Sylvia Scarlett – also directed by Cukor – in which Hepburn cross-dresses as a man named Sylvester. (“I won’t be a girl. I won’t be weak, and I won’t be silly. I’ll be a boy, and rough, and hard,” she cries out in the film.) Hepburn’s second film with Cukor was Little Women, in which Hepburn plays Jo March, a character widely understood to be the avatar for writer Louisa May Alcott, who is often presumed to have been queer or trans. In her 40s and beyond, Hepburn had a reputation for playing middle-aged spinsters, an image that was embraced by the Hollywood publicity machine and the public. It seemed fitting, considering her famously cantankerous attitude and unmarried status

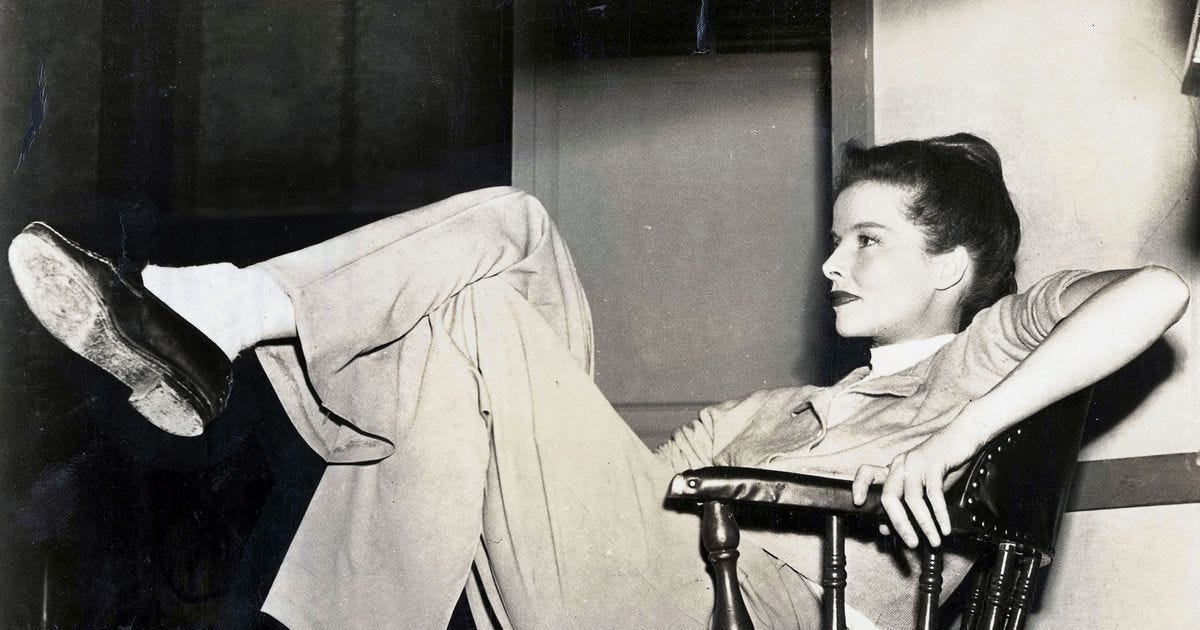

Returning to the question of bodies, Hepburn’s physical contortion is just as illuminating as her choice of fashion and roles. Compelled to wear elegant dresses in many of her film roles, ‘movie star’ Hepburn often moves with a sort of vigorous rigidity that, in her most thrilling moments, dissolves into playful dynamism. Off-screen – or at least not in front of a movie camera – Hepburn has a much more languid, relaxed way about her. Think, for example, of her iconic 1973 interview with Dick Cavett, where she puts her leg up on the table to get more comfortable. This post in the r/vintageladyladyboners subreddit, aptly named ‘Katherine Hepburn sitting in chairs,’ is especially illustrative of Hepburn’s defiant contortion.

If you’re familiar with a particular side of internet culture, you can probably guess that Hepburn’s unique manner of sitting in chairs has led to a renewed interest in her supposed queerness. But this question existed long before internet memes. It’s frequently been assumed that Hepburn herself was queer and had romantic relationships with women, including socialite Laura Harding, who one biographer maintained she took on her honeymoon. In a conversation with biographer and friend Scott Berg, Hepburn referred to her live-in companion Phyllis Wilbourn as “My Alice B. Toklas,” Gertrude Stein’s longtime partner. Gore Vidal seconded Scotty Bowers’ claim that he frequently set Hepburn up on dates with women, while Larry Kramer has alleged that Hepburn and partner Spencer Tracy were both gay and set up together for publicity purposes.

What we know for sure is that Hepburn certainly had queer friends in her life, though this circumstance was not uncommon at the time. George Cukor, her director and frequent collaborator, was semi-openly gay, and Hepburn also worked with Dorothy Arzner, a lesbian filmmaker. It has become a generally accepted fact that Hepburn’s co-star, Cary Grant, was in a romantic relationship with his “roommate” Randolph Scott for many years. (Grant has also been credited as delivering the first movie line in which the word “gay” is used to mean “homosexual.” “Because I just went gay all of a sudden!” is uttered by Grant in Bringing Up Baby (1938), in which Hepburn also stars.)

Regardless of the truth of these suppositions, Hepburn has long been figured as a queer icon. Not just because of these rumors, but also because of her style, the roles she played, and the defiant way she chose to live her life. The way she behaved, moved, and acted has been recognized as queer throughout both the 20th and 21st centuries. (To give you an indication of her cultural significance, there was a lesbian bar in Philadelphia in the 1980s and 1990s called Hepburn’s which featured photos of the actress in Sylvia Scarlett as decoration.)

Hepburn and Grant, who have both left behind something of a queer legacy, are perfectly suited for their roles in Holiday. Grant plays Johnny Case, an energetic working man who falls for the beautiful but vapid Julia Seton (Doris Nolan), the daughter of a wealthy businessman. Hepburn plays Linda, Julia’s older sister, who calls herself the “black sheep” of the family and does not hold the same regard for the family business as her sister does.

The contrast between Johnny and Linda is made immediately clear. Grant arrives on the scene with boundless energy. After showing up on the doorstep of his two best friends, Nick (Edward Everett Horton) and Susan (Jean Dixon), Johnny explains his way of getting through life. “When things get tough and I feel a worry coming on,” he starts, before doing a somersault, or what’s known in the film as a “flip-flop.” Hepburn’s arrival is similarly energetic, but when Linda walks in she’s all angles, dressed in a square-shouldered fur coat and a flat-topped hat that sits diagonally on her head. Meanwhile, Julia is wearing the silliest little hat you’ve ever seen, pearls, and an ostentatious fur wrap around her arm. Linda’s presence is contrasted with her softer-looking sister (who also happens to be a blonde), though we will later learn this softness is just as much of a mask as Linda’s hardness is.

Linda takes an instant liking to Johnny, and he to her. When he finds her eating an apple and she asks him if he would like a bite, he chomps down on the half-eaten fruit like it's nothing, easily tearing down whatever boundaries might have existed between a future brother and sister-in-law. Linda’s initial sharpness begins to smooth in Johnny’s presence. We find her at her most languid in the playroom, the only room in the house that feels actually livable and where she and Johnny spend most of their time. Meanwhile, Johnny becomes more buttoned up as Julia tries to mold him into the kind of man she wants him to be, but not the man he really is.

The most stupendous scene in the film – and one of the greatest in any film ever, truly – involves a particular acrobatic feat. Johnny, who is prone to doing back and front flip-flops whenever the spirit moves him, promises to teach Linda how to do them too. They finally get their chance up in the playroom with Nick and Susan. Linda and Johnny jump over the back of the couch as it topples over, and the film suddenly feels like it’s turning into Singin’ in the Rain. Linda stands on Johnny’s shoulders and then leaps off as they both do simultaneous front flip-flops, landing on the floor with their legs spread wide in perfect synchronicity. Here, Grant brilliantly displays what Angelica Jade Bastién calls his “acrobatic grace,” and this time Hepburn gets to join him. Johnny and Linda are overjoyed at the feat they’ve just accomplished, only to be rudely interrupted by Julia and Mr. Seton (Henry Kolker), who are incapable of understanding why two people would do such a silly thing.

Though their affection for one another feels genuine, Johnny also has something Linda wants. His somatic freedom - as well as his philosophical optimism – is something Linda does not herself possess but desperately desires. Linda often describes a feeling of restlessness and even despair. “I could curl up and die right now,” she says to Julia when she begins to consider the fact that her sister will soon be leaving her. Later, during a confrontation with her father, Linda finally tells it like it is. “I can’t stand it here any longer, it’s doing terrible things to me,” she tearfully declares.

Linda wonders if the grass is greener over on Johnny’s side, and she asks him as much. In response, he describes his plan for life, which involves not simply working for money, but actually figuring out what he’s working for. When he explains all of this to Linda, she looks completely enamored at having found someone who finally understands her own perspective. “He’s like spring, he’s like a breath of fresh air!” she tells Julia, who mistakenly believes that Johnny will burn “steadily” like her father’s trusted cigar. Linda aspires to have that passion and autonomy that Johnny so readily possesses, to the point where her desire to be with Johnny almost collapses into wanting to be Johnny. Their dynamic doesn’t quite fit within the boundaries of a classic Hollywood romance, but it does resonate as a uniquely queer experience of desire.

Though all of the characters are in their twenties or older, Holiday in many ways feels like a story about youth. It’s almost a coming-of-age narrative, as we see the characters begin to work out who they really want to be when they “grow up.” A thirty-year-old Hepburn has never looked younger than she does here, and this is in large part due to her heart-wrenchingly sincere performance. In Holiday, perhaps more so than in any of her other roles, there is an earnestness to Hepburn’s biting wit and feisty recalcitrance. It is forceful, but you can also see through it, down to the bones of her vulnerable, childlike self. The characters – especially Johnny and Linda, but also Linda’s terribly trapped brother, Ned (Lew Ayres) – act like teenagers rebelling against their parents more than they do settled adults. Linda and Johnny seem at times almost impossibly naive, with Johnny’s belief that Julia and Mr. Seton will understand and accept his unconventional life plan and Linda’s complete ignorance about Julia’s rotten insipidity.

When Mr. Seton calls Linda and Johnny’s ideas about the future those of seventeen-year-olds, Linda replies, “We’re all grand at seventeen, it’s after that the sickness sets in.” Does anyone ever outlive their teenage dreams? During Linda’s confrontation with her father in the playroom, Linda acts like a teenager threatening to leave home, and Mr. Seton a parent ousting their wayward child. “You distress me. You cause nothing but trouble and upsets” he tells her before suggesting she should leave the house altogether.

Linda’s adulthood has been forcefully deferred, both by her own stubborn restlessness and her father’s infantilizing treatment of her. “There’s no cause for temper, child,” he says when Linda slams the door upon his arrival at her inner sanctum. She tries and tries to explain to her father what the playroom and the party she’s tried to throw mean to her, but to no avail. “Once more, Father, this is important to me. Don’t ask me why, I don’t know. It has something to do with this room and when I was a child and good times in it,” she declares. The playroom is the only place she feels safe, the only place she can be herself. It is her home.

Linda and Johnny both feel at times hopelessly trapped by the propulsive force of modern society and the demands of capitalism. Their refusal to abide by normative timelines recalls another concept associated with a particularly queer type of living: queer time. Proposed by scholar Jack Halberstam, “queer time” describes resistance to the temporal ideas that structure systems like capitalism and heteropatriarchy. The lives of queer and trans folks often progress in different – and sometimes non-linear – timelines than their straight peers, and Halberstam takes this lived experience as a potentially radical intervention. Resistance, and the instinct to hold back in some way, can be just as subversive as moving forward.

Linda is not alone in her childlike sensibilities. Johnny’s closest friends, Nick and Susan – who Linda takes an instantaneous and familiar liking to – also have a youthful energy to them though they appear to be middle-aged. They are thrilled to be invited into Linda’s fittingly named playroom and happily begin an impromptu puppet show, much to Linda’s delight. Linda’s brother Ned, the youngest of the Setons, has been saddled with business responsibilities but appears impossibly young when he gets wistful (and drunk), especially around his big sister. (It’s also worth noting that Ned is by far the swishiest of all the men in this movie, filling the role of the flamboyant (read: gay) sidekick who is never actually named as such.) With his youthful aspirations to be a musician squashed, he is left weighted down by adulthood.

There are plenty of films made during the era of the production code that found ways to be erotic and sensual despite studio censorship, but Holiday is not one of them. Certainly, Hepburn does a believable job convincing us she loves Johnny in a romantic sense, but the strongest feeling transmitted is that of someone longing for connection, longing for kinship, longing to be free. Johnny is eminently lovable and also fervidly free, and Linda desires that kind of embodied courage more than anything. The electricity between the two of them is about self-reflection and equality. It’s queer kinship.

The lack of eroticism between Johnny and Linda actually plays to Hepburn’s strengths as an actor and as a woman. George Stevens, the director of Alice Adams (1935), once told biographer Charles Higham that he had to teach Hepburn how to behave during love scenes. “She had always thought that to play a love scene with a man involved standing up straight and talking to him strong, eye to eye,” he recalled. In this case, Hepburn’s aversion to passively receiving a man’s advances works in her favor, because Linda and Johnny are equals, and this is exactly what makes their association so potent.

The queer (read, also: off-kilter or unusual) connection Linda feels to Johnny is immediate. Johnny has found “his people” in Nick and Susan, and Linda longs for that kind of natural affinity. Julia and Mr. Seton may be Linda’s family, but what Linda comes to understand is that they’re not her kin. Johnny, Nick, Susan, and poor old Ned, are Linda’s kin. Linda’s never felt so understood by anyone before, though she waffles in her commitment to these ideals when faced with an opportunity to honestly address her feelings. Nick and Susan, who understand Linda’s dilemma before she even does, are there to offer support, like a family might do. “If you did anything else than what you’re doing, then you wouldn't be what you are,” Nick reassures her. “I love you two,” Linda says, getting down on her knees as if in supplication. Within this club, Linda is no longer a black sheep, and Nick and Susan accept her with open arms.

Linda understands that something quite unusual is happening, and the freedom that comes from truly being seen and understood by others is thrilling to her. “I feel alive, and I love it. I feel at last something’s happening to me,” she tells Ned, expressing her feelings for Johnny and everything he represents. At first, she describes feeling ashamed that others might be able to “see” her love for Johnny, but then she realizes she’s lost the shame that once resided in her body. She no longer feels embarrassed by wanting what she wants, and for being who she is. Meanwhile, Johnny has his own revelation after Mr. Seton offers up a charmed life on a platter and he sees his dull future flash before his eyes. “I love feeling free inside even better than I love you, Julia,” he proclaims, turning down Mr. Seton’s overbearing proposition.

Linda is unable to contain the passion she has for her new family and way of life, composed of queer fellows and intellectuals. After Johnny decides to finally end things with Julia, Linda realizes that Julia never loved him at all, and she sees her own queer future laid out before her, one that is very different from the future her family might have imagined for her. “Try and stop me, someone. Oh please, someone try and stop me,” she practically yells as she’s running out the door. It’s Hepburn at her most theatrical, performing for a stunned audience of three. It’s as if she’s giving a farewell speech to her family before going on to live her real life, though she promises to come back for Ned who is, after all, both her blood relative and her kin.

Fittingly, the film ends with bodies animated by joy. In a classic rom-com moment, Linda rushes to meet Johnny before his ship leaves the harbor. Even before Linda’s arrival, Johnny is skipping with happiness, overjoyed at the fact that he’s retained his autonomy and escaped the Seton’s soul-sucking clutches. He walks down the hallway of the ship, doing a handstand and then a backflip before landing gracefully on his stomach. “Is this where the club meets?” Linda asks, turning the corner at precisely the right moment. Nick and Susan are just as thrilled to see Linda as Johnny is, and they practically cheer from the doorway. Johnny pulls Linda down to the floor with him and they share a brief kiss before the screen fades to black.

On the surface, it’s a cookie-cutter ending to a near-perfect screwball romance. But upon further inspection, another sentiment emerges: queer joy. The loneliness and desperation that Linda feels is a recognizably queer feeling, and the camaraderie that develops between her and Johnny is best described as a sort of queer kinship. Coupled with the demonstrably queer legacy of Hepburn’s career, the film thus appears before us as a tender paean to the sort of bonds that emerge between those who are queerly situated within the world around them. Without the queer kinship she finds with Johnny, Nick, and Susan, Linda – along with the rest of the black sheep of the world – would be forever trapped in the playroom, yearning all by her lonesome. “Baaa,” says Linda. “Baaa,” says Johnny, in perfect harmony.

“Grant has also been credited as delivering the first movie line in which the word “gay” is used to mean “homosexual.” “Because I just went gay all of a sudden!” is uttered by Grant in Bringing Up Baby (1938), in which Hepburn also stars.” Fascinating fact in an excellent piece, thank you!