Temim Fruchter’s Lavish Queer Jewish Storyelling

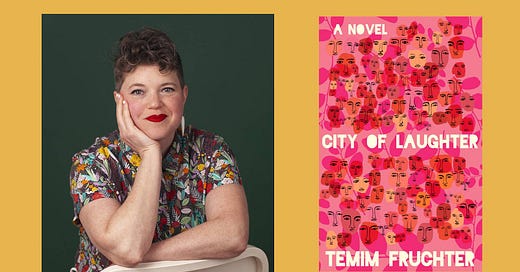

Chatting with the author of 'City of Laughter'

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet, monthly playlists, and a free sticker.

I love talking to novelists about their work, because I find fiction writing such a fascinating (and honestly a little perplexing) enterprise. Recently, I read a book that was so inventive and ambitious that I knew I wanted to speak with its author. Temim Fruchter’s City of Laughter follows Shiva, a queer woman in her early 30s. Mourning the loss of her father and recovering from her first queer breakup, Shiva longs for familial connection, something she’s not getting from her closed-off mother. This desire leads Shiva to the study of Jewish folklore and to Ropshitz, Poland, a town formerly known as the City of Laughter. Fruchter beautifully weaves together Shiva’s search for her origins with her evolving understanding of queerness, giving mythology and folklore just as much weight as any empirical fact. As a novel that centers on storytelling, City of Laughter cleverly plays with form and draws our attention to the power of stories as a form of ancestral and cultural remembering, not to mention personal affirmation.

I spoke with Temim about the process of writing this book, her relationship with storytelling, and how she unspooled some of the novel’s heady themes. If any of this sparks your interest, I’d encourage you to seek out a copy of the book for yourself. Happy reading!

Could you talk a little bit about how you came to write this book and what the first kernels of inspiration were?

I think the very first kernel of inspiration was looking at some old pictures of my maternal grandmother. She was a very dignified and private woman, but the pictures from her youth show someone mischievous-looking with starlet-level glam. As a grown queer femme, I was moved to feel like I recognized something in my grandmother, sartorially and spiritually, that reminded me of my own femme energy. This got me imagining a queer lineage - not because I'm positing all of my ancestors were literally queer, but because it started to occur to me that, even if they had been, given the erasure of so many queer and trans stories, it would be impossible for me to know. Playing with that possibility was permissive and exciting. The second was being in Warsaw in 2012, and traveling to Ropscyze, where my maternal great-grandparents' shtetl once stood. Standing in that place, which is mostly now just road and trees and grass, I felt at once like the place was thrumming with ghosts and spirits and that my ancestors were still here, and also like this was just somewhere now unremarkable, and that anything I was feeling was pure projection. I think this is a complicated duality that many of us in diaspora communities experience when going back to somewhere ancestral, and I wanted to write into it - that ambivalence, that bothness, since I think both feelings were real.

The characters in City of Laughter inhabit different roles in regard to relaying stories or folktales. The main character, Shiva, considers herself a storyteller first and foremost, then there is the mysterious messenger character, and then there’s Shiva’s grandmother, who seems to speak almost exclusively in folktales and allegories. As a writer, do you see yourself as occupying any of these roles? A storyteller, a messenger, a purveyor of history, mythology, etc...

This is a great question! I do see myself as a storyteller, though usually not in a capital S kind of way. I love to spin a yarn, to tell the long version, to make people laugh, to generate intrigue. As I wrote this book, I felt more like a collector of various kinds of scraps, a collage artist, which excited me, too. Maybe my S grew a little bit more capital. I don't think of myself as a messenger, necessarily, but god only knows I am listening for and watching for and looking out for messengers all the time.

I love how the book engages with time, especially how you bring in the concept of block theory – how past, present, and future all exist simultaneously. Do you think queer folks and their communities have a distinct way of existing and perceiving time? I would love to hear more about how you conceptualized time in regard to queerness and Shiva’s (queer) relationship with the past.

I so appreciate this question! I really value conceptions of and imagination about 'queer time' - how it factually moves differently, how our milestones look different, how things can be less linear, but also, how queerness allows room for more expansive thinking about what's possible temporally. I also think writing queer fiction - and writing fiction, generally speaking - is such a thrilling opportunity to experiment with and refigure time, and to insist that, even as we are inside of it, and even as it is unavoidably marching along, we can experience it in new ways.

As I've done my own thinking about my ancestral line and how to feel closer to it, I kept having this visceral impulse that it was vertical, not horizontal. This made me think more about the orientation of time - when I hear 'linear,' I think horizontal, I think timeline. But my own vertical impulse made me start to think about more imaginative and radical theories about how time works. Theories that, to be very clear, I don't fully understand myself! But both in this book and in my life more broadly, time is something I'd rather submit to not fully understanding the expansive workings of than claim to fully know the limits of. I wanted my novel to be a space where queer time pressed up against the page - multidirectional, complex, simultaneous, and ready to challenge our everyday ideas about how it actually works. At the heart of the novel is the assertion that there is more in this universe than we can readily see or experience unless we're really paying a certain kind of attention. I think of this, in some ways, as a queer kind of attention. And once we start to pay that sort of attention, we are rewarded with a richer, more mysterious, and more shimmering experience of the reality we're living.

I was quite taken with how you describe femme identity/embodiment in the book. You write: “It meant sartorial power and aesthetic largess; it meant volume and texture.” Can you share with me how you conceptualize femme-ness as an (I think under-theorized) aspect of queerness? How does femme connect to the book’s larger themes of history, ancestry, kinship etc.?

I really wanted this, among other things, to be a femme novel, in both form and content. For me, being femme has been somewhat fluid in terms of my gender expression, but it has always been about being big and effusive and loud and adorned. Maximalist. When I first came into femme identity myself, I had been presenting and identifying as masc of center for a number of years. Femme became permission to paint myself again, to bejewel myself, to not be so subtle. Now, as an older queer, I understand that masculinity can be adorned, too, but femme, for me, will always be the moment I permitted myself the opulences of aesthetic gender expression. And so, to this day, I understand it as a kind of permission. To be lipsticked and loud; to strut and to peacock. The fact that femmeness is at once a kind of exaggerated performance and also a profound kind of sincerity really excites me. I agree with you that it feels under-theorized, and I think about how fiction can contribute to a deeper understanding of what femme can mean. Not by positing a particular definition or theory, but by depicting femmes of various kinds in all of their aesthetic glory, in the ways they move through the world, through fashion and expression and desire.

The book explores queer resonances across generations, an intimate, familial historiography that invokes a larger project of excavating the queer past. I was reminded of one of my favorite queer scholars, José Esteban Muñoz, who wrote that “queerness has an especially vexed relationship to evidence,” and Heather Love’s book Feeling Backward, which reclaims the less prideful examples of queer figures in history. How did you conceptualize the idea of flushing out the queer elements of (familial) history when, as Muñoz alludes to, there is often pushback to claiming a person or a place as queer without explicit evidence?

I'm so delighted and honored for José Esteban Muñoz's scholarship to be invoked in the context of my book. His work has been so important to my understanding of the power and presence of both queer possibility and queer futurity. I thought a lot about evidence, or the lack thereof, as I was writing this book. This goes, too, for external events; plot points, if you will. Encounters or conversations or old memories. Sometimes, I have this feeling, like: Did I imagine it? Or misremember it? Regardless, I am left with a certain feeling, the emotional truth of a Something having happened. I wrote into the book like this - like the proof or the hard data were never the point. And then when it comes to queerness, to queer desire, to queer lineages. Evidence is certainly important in many contexts, but for something so intimate, so profoundly existential, it seems to me that a different and much more fluid kind of metric is required. Something affective, something intuitive, something about memory. I am so in love with queer imagination, which is a bottomless resource that I believe exists despite evidence, not because of it.

There are several different love stories – and distinct forms of love – in the book. The Messenger reminds us that "a love story is the engine at the center of anything" and that longing and desire are often transmitted through generations. What are some love stories – whether fictional, 'real', imagined... – that have resonated with you and propelled you forward?

Too many to name! As a proto-queer Orthodox Jewish teenager, I discovered and kept coming back to the ancient love story of David and Jonathan. Rewriting it, projecting onto it, modernizing it, filling in the gaps. I have always been a deep romantic, gravitating to a story propelled by love, even/especially in unusual or unorthodox forms. Early on, Jeanette Winterson's books and Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red taught me that a love story could be absurdly grandiose, queer, oddly-shaped, lyrical. I do believe that a love story is the engine at the center of anything, though, far from being central only to romance or romantic love. Love as the hot beating heart of a story. I will say also love a rom com. Good ones and terrible ones. Anything Nora Ephron does feels a part of my cellular makeup.

I wanted to end with a bit of a process-y question: Who/what/where were most essential in your process of writing the book? I'm thinking for example of people, other texts or pieces of media, writing spaces/environments.....

People-wise, I think first of the people in my life who are most supportive of my writing. My partner, who happily single-parents our cats for weeks on end when I go on residencies. My dearest friends, who brainstorm and commiserate with me, who embark on accountability contests alongside me as we trick ourselves into immersing in our writing projects. Space-wise? Mostly just a tidy quiet stretch and good lighting. I love writing in the early morning for this reason. Other texts were so important, too. Far from being someone who eschews reading kindred books while I'm working on a project, I hang out with them. I think of them, as my friend the writer Maud Casey once taught me, as companion books. Books to visit and dip into for inspiration or company, books that might speak, in some important way, to the text I'm working on. Some examples of these for City of Laughter: Alexander Chee's Edinburgh, Marie Helene Bertino's Parakeet, Jordy Rosenberg's Confessions of the Fox, Helen Oyeyemi's Gingerbread, Andrea Lawlor's Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl, Nicole Krauss' A History of Love, Victor LaValle's The Changeling, Zeyn Joukhadar's The Thirty Names of Night, to name a few. Queer storytelling and brilliant retellings and musical language and magic that appears in unexpected and refracted ways.

You can purchase City of Laughter at Bookshop or at your local independent bookstore.