She’ll Eat You Alive

Stephanie Rothman’s feminist take on the lesbian vampire film

Do you like lesbians? Do you like pop culture? Then you should subscribe to this newsletter. Even better, you should sign up for a paid subscription, which will get you more sweet sapphic content and allow me to keep writing things like this.

To start: a brief history of the lesbian vampire genre. While it may seem like a fairly niche category, the lesbian vampire story goes back at least two centuries and is in fact quite influential. One of the earliest examples of this narrative is the 1872 novella by Sheridan Le Fanu, Carmilla, which actually predates Bram Stoker’s Dracula by fifteen years. Vampires, then, have been associated with lesbianism since their early introduction in fiction. In addition to being an early vampire text, Carmilla is often cited as the first British book to explicitly depict a lesbian relationship. An even earlier vampire story is the tale of Countess Elizabeth Báthory, a Hungarian noblewoman from the 16th century who allegedly murdered hundreds of young women and bathed in their blood.

In the Golden Age of Hollywood, the most famous lesbian vampire story is 1936’s Dracula’s Daughter, which, despite its obvious illusions to Bram Stoker, is said to have been inspired by Carmilla as well. The genre had a resurgence – albeit in a slightly different context – with the arrival of the lesbian vampire films of the 1970s. This genre emerged within the larger umbrella of low-budget exploitation films, and many of them were explicitly erotic and/or sensationalized in nature. Many of these films, including 1970’s The Vampire Lovers, were based either explicitly or implicitly on Carmilla. Others, such as 1971’s Countess Dracula, were inspired by the story of Elizabeth Báthory. There were also a few higher budget explorations of this theme during the period, including 1971’s Daughters of Darkness, which starred Delphine Seyrig, and Tony Scott’s 1983 film The Hunger, which starred Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, and Susan Sarandon.

In recent years, there have been various efforts to redeem the lesbian vampire story, which has historically painted lesbians as villainous, monstrous figures. The 2014 Canadian web series Carmilla, which is based on the novella, became a worldwide phenomenon as fans latched on to the relationship between the two women protagonists. More recently, Netflix’s First Kill depicted a lesbian vampire love story that was more empowering than it was predatory, to the delight of viewers.

But let’s turn back to the lesbian vampire exploitation film for a moment. Almost all of these films were European, and almost all of them were directed by men. The guiding principle of these films is the idea that there is something terrifying about the lesbian or bisexual desire to consume the other, and something terrifying about women’s desire in general. (While they were called “lesbian vampire” films, more often than not they actually depicted bisexuality.) These films were not, as a whole, meant to be “empowering” to actual queer women, though one could potentially read them that way with a little (or a lot) of imagination.

In this case, there is at least one exception to the rule. In 1971, Stephanie Rothman’s lesbian vampire flick The Velvet Vampire1 was released. The film follows Diane LeFanu (the striking Celeste Yarnall), a seductive bisexual vampire who lives in the Mojave Desert. Diane invites a free-spirited married couple to come stay at her desert home, where she sets her sights on seducing them both. The film was in part inspired by the success of Daughters of Darkness, which follows a similar plot line involving the seduction of a married couple.

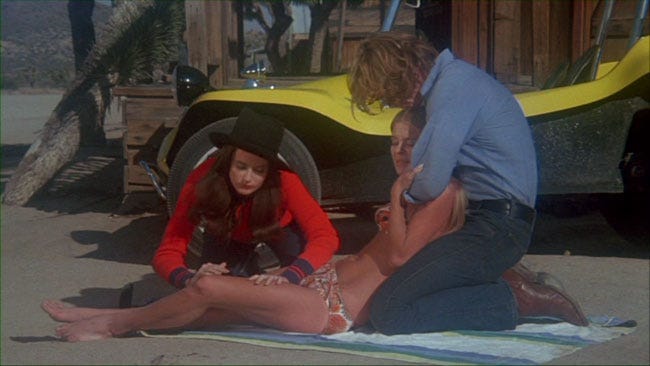

The Velvet Vampire is not only a rare lesbian vampire film directed by a woman, it also has the unique distinction of being one of the few to be filmed and set in America. The desert may seem like an odd place for a vampire to live, but then again, many of the choices Rothman makes here are a bit odd. Diane’s desert home is an evocative setting. On the one hand, there’s not a lot of food (re: victims) in the desert, but there are also not many prying eyes either. (In a genius re-working of the 19th-century vampire story, horse and buggies are replaced by a literal dune buggy.) At the time of the film’s release, the California desert was still very much associated with Charles Manson and his gang, giving the environment an even more sinister feel. The film’s soundtrack is also unique – and very American – combining blues, folk, and psychedelic rock music as a means to create a dreamy, haunting atmosphere.

Rothman’s take on the lesbian vampire flick is an explicitly feminist one, which is one of the reasons the film is worth revisiting. In some ways, it’s a parable about the limits of sexual liberation and what it looks like when free love goes too far. The married couple, Susan and Lee, might be down for a little swinging, but they’re certainly not down with death by vampire.

It initially appears as if Lee and Diane are going to be the primary romance of the film, as he is almost immediately enamored with her. But Lee is something of a wet noodle of a character, and he can’t stand up to Diane’s voracious appetite. Susan is initially wary of Diane, in part because of her obviousness in seducing Lee. But Susan comes around to Diane’s side in one of the most oddly erotic moments in the film. While Diane and Lee are getting hot and heavy inside of a barn, Susan has an unwanted encounter with a snake while she is sunbathing. Diane heroically comes to the rescue, cutting open Susan’s leg with a knife and sucking the venom out. After this, Susan is the one enamored with Diane, while Lee has begun to get suspicious.

If a sweet sapphic love story is what you’re looking for, The Velvet Vampire won’t be very satisfying. Diane and Susan do not run off into the sunset together, but the film does reverse the typical ending of the lesbian vampire flick in an interesting way. Diane tries to seduce Susan in the exact same way she seduces Lee (she uses the very same line, in fact), but Susan discovers Lee’s freshly-drained body hiding behind the curtains. She escapes from Diane’s home and gets on the bus, only to discover that Diane has followed her. (It’s important to note here that there is an incredible chase sequence where Diane stands perfectly still on a slow-moving escalator in pursuit of Susan, looking unbothered and glamorous.)

Susan, who at this point has realized Diane is a vampire, finds a stall outside of the bus station selling crosses, and she grabs a handful to protect herself. The onlookers join in the crusade, and Diane finds herself surrounded by crosses and frying in the sun after Susan rips her cape and hat off. To passersby, it might look like a woman going insane, when it's actually a vampire finally meeting her fate.

With this unexpected ending, Rothman was looking to flip the script. Rather than simply portraying the typical narrative of the villain and the victim, she “decided to reverse the convention and have the man enjoy a masochistic orgasmic death by vampire while the woman battled back.” This conclusion isn’t so much pro-queer as it is pro-woman, but it’s certainly a departure from what was expected at the time.

Most films in this genre ended with the man killing the vampire woman, essentially restoring a social order gone awry. In this case, rather than being killed by the heroic man, the (bisexual) vampire is killed by a prejudiced society. As Adam Nayman writes, “in the end, she’s like a scapegoat for the primal desires she stirs up in the people around her.” Diane is both monstrous and persecuted, and whether or not her persecution is justified is up to the viewer to decide. Either way, she’s clearly a disrupting force in society, even if she is ostensibly defeated in the end.

Though The Velvet Vampire has received some renewed interest2 over the years, it didn’t do well at the box office and never received the reception the producers hoped it would. Director Susan Rothman was the first woman to be awarded the Directors Guild of America’s fellowship, and at the time was known for her previous exploitation film, The Student Nurses, which has since become a cult classic. Rothman was the protege of Roger Corman, the famed American independent filmmaker, and The Velvet Vampire was produced by his company, New World Pictures. Corman was also a mentor to a host of other young filmmakers including Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdonavich, and James Cameron, who, as you know, have gone on to have prolific film careers. Rothman would go on to direct a few other low-budget films in the ‘70s, but never directed another film after 1974.

What’s most interesting about The Velvet Vampire is its position within the often sexist and homophobic world of exploitation film. Rothman was one of the few women working within the genre, and that fact alone is worth exploring. But the film also poses some intriguing questions about intention and reception. There is often a thin line between exploitation and subversion, and The Velvet Vampire walks it carefully. By working within the confines of the genre but exposing its ideological underpinnings, Rothman defines a new canon without entirely disposing of the old one.

There are plenty of other contexts in which these dynamics play out. Think, for example, of lesbian pulp novels, which have a reputation for being trashy or offensive but were re-defined by lesbian writers who created affirming stories within the genre. Or, consider rape-revenge films. Early films like I Spit On Your Grave were almost gleeful in their exploitation of women’s pain, while feminist rape-revenge films like Revenge re-orient our perception. The erotic thriller is a close cousin of the lesbian vampire flick, and these films, too, can easily oscillate between subversive and exploitative depending not just on the filmmaker’s intent, but on the viewer's perspective.

One of the things that’s so compelling about cinema as a cultural object is the way it travels through space and time. A re-appraisal of The Velvet Vampire will certainly generate different responses today than it would have in 1971, though not all of these responses will be positive. Regardless, the film still has a lot to teach us today, even if it’s just the dangers of riding around in a dune buggy with a vampire.

You can stream the film on Tubi and Shudder.

The film’s influence can be seen most clearly in Anna Biller’s 2016 film The Love Witch, which has a lot in common with The Velvet Vampire both thematically and visually.