This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet, monthly playlists, and a free sticker. I’m a full-time freelance journalist – your support goes a long way!

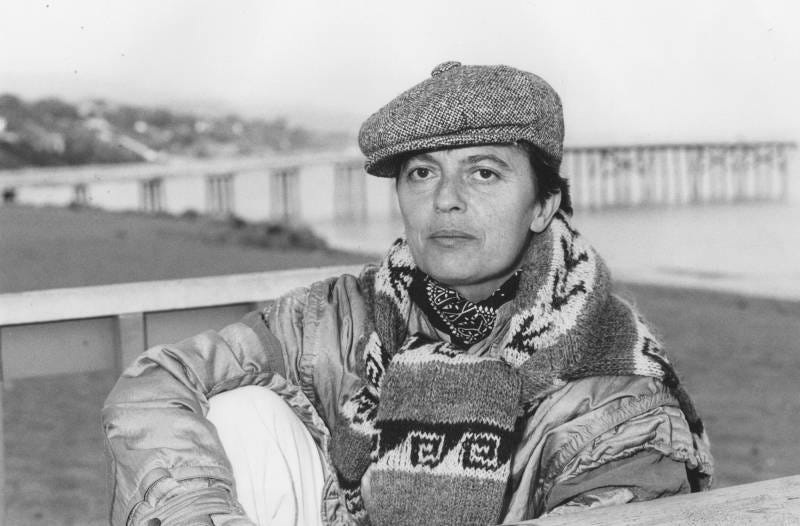

Though less well known in America, Monique Wittig was one of the most prominent figures in the French feminist movement of the 1970s. In 1969, she published her novel Les Guérillères, which follows a war of the sexes and is often considered the founding text of French feminism. Shortly thereafter, Wittig co-founded the Mouvement de libération des femmes (MLF), but later fled to the United States in the mid-70s after supposedly being “chased out” of Paris for her radically lesbian-specific activism.

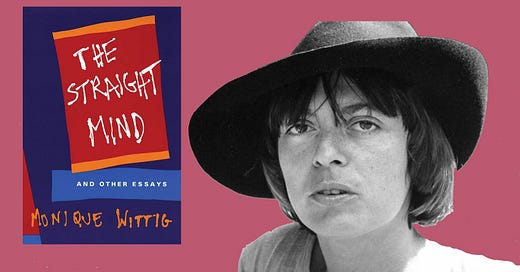

Following the move, Wittig turned her attention to gender theory, publishing her eminent essay “The Straight Mind” in 1980. The essay was then republished in her collection The Straight Mind and Other Essays in 1992. Drawing from the likes of Simone De Beauvoir, Wittig’s writings were both influential and controversial, sparking complex consideration from American scholars such as famed gender theorist Judith Butler, among others.

Today, we’re diving into the eponymous essay, which includes several provocative theories and an iconic final line that still delights and displeases today. (More on that later.) Wittig begins the essay by considering the power of language, one of her most enduring fascinations. She contends that language and the discourses that populate our culture have material effects on human beings, not just reinforcing but producing oppression. Language acts on the body. She writes, “The ensemble of these discourses produces a confusing static for the oppressed, which makes them lose sight of the material cause of their oppression and plunges them into a kind of ahistoric vacuum.”

In the 20th century, the language of the human psyche and the relations between people (read: men and women) were exclusively defined by psychoanalysts. Foundational psychological theories – such as the Oedipus complex, castration anxiety, and penis envy – rest on binary sexual difference. This is the only language provided for patients to speak about their lives.

Oppressed people, such as gays and lesbians, can’t communicate their experiences and feelings within this framework and are forced to say what psychoanalysts want to hear. Wittig calls this dynamic – which could be defined as an “incitement to discourse,” to use a Foucauldian term – a “cruel contract which constrains a human being to display her/his misery to an oppressor who is directly responsible for it.” She suggests that it’s nearly impossible for lesbians, feminists, and gay men “to communicate in heterosexual society.”

Such theories are based on the category of sex, a structural language that defines social life. In “Utopian conceptions: rethinking the straight mind,” Clare Whatling writes, “To Wittig there is no such thing as a biological distinction between the sexes. Maleness and femaleness are not natural facts but social positions.” Wittig doesn’t recognize a sex or gender binary (and in any case, the two categories are synonymous). “Gender is used here in the singular because indeed there are not two genders. There is only one: the feminine, the ‘masculine’ not being a gender. For the masculine is not the masculine, but the general,” she writes. Because they are the “general,” or the universal, men are not sexed. It’s only women, a derivative of the general, who have a sex.

These discourses confer oppression on their denizens. Though in the modern age some have accepted that there is no nature, just culture, one aspect of culture still resists examination – heterosexual relationships. As Wittig puts it, “The discourses which particularly oppress all of us, lesbians, women, and homosexual men, are those discourses which take for granted that what founds society, any society, is heterosexuality.” These invisible foundations silence those who don’t speak using the terms of heterosexual discourse. Furthermore, “these discourses deny us every possibility of creating our own categories,” Wittig writes.

In order to illustrate the “material oppression of individuals by discourses,” Wittig uses the example of pornography. She writes that “pornographic discourse is part of the strategies of violence which are exercised upon us.” This formulation brings to mind the works of Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon, both of whom were on the anti-porn side of the 1980s sex wars. MacKinnon has argued that all sex between cis men and women is oppressive, or to put it another way, that the “difference” between men and women is based on sexual dominance/submission.

In “The Straight Mind,” Wittig focuses not just on the practice and ideology of sexual relations, but the way language structures reality and material circumstance. Heterosexual discourse structures social relations while hiding the preordained, organizational nature of that construction. Heterosexuality flows through numerous overlapping discourses and seems to come from nowhere (i.e., the “natural” body), thus obscuring its origins. This notion may sound familiar to gender scholars, as it aligns with the work of one of Wittig’s fiercest critics and successors, Judith Butler. Indeed, Butler’s theory of gender performativity follows a similar rhetorical trajectory.

Wittig’s primary motivation is to explore how heterosexual discourse and the category of sex can be undermined and eventually disposed of altogether. She argues that the most effective way to achieve such subversion is through lesbianism. Wittig maintains that it is impossible to reject heterosexual discourse because “to do this would mean to reject the possibility of the constitution of the other and to reject the “symbolic order [...] As such, lesbians and gay men “cannot be thought of or spoken of, even though they have always existed.”

Because it is unspeakable, homosexuality does not represent the “other” within heterosexual discourse. Instead, “the straight mind continues to affirm that incest, and not homosexuality, represents its major interdiction.” (This follows Claude Lévi-Strauss’ writings on the incest taboo, which he claims exists to prevent in-group sexual relations. The title of Wittig’s essay references Lévi-Strauss’book The Savage Mind, which explores “untamed” human thought.)

Wittig writes that “straight society is based on the necessity of the different/other at every level.” It cannot function without this structure. Still, lesbianism and homosexuality haunt the periphery of the heterosexual system, and it is feasible – despite Wittig’s previous claim of impossibility – to opt out of such a system, at least in theory. In fact, Wittig sees it as a moral imperative. “If we, as lesbians and gay men, continue to speak of ourselves and to conceive of ourselves as women and as men, we are instrumental in maintaining heterosexuality,” she writes.

Instead, the directive here is to completely dissolve the category woman “politically, economically, and ideologically.” Within this structure, refusing heterosexuality is synonymous with refusing to exist as a man or woman. This idea leads to Wittig’s famous final line: “Lesbians are not women.” For Wittig, the lesbian is a powerful figure because she is “beyond the categories of sex” – in all social realms – due to her refusal of heterosexuality.

Leaning into this outside-ness may be the most productive way to upend the heterosexual dichotomy – a system of domination – of sex. Wittig wants to destroy the category of sex altogether. Lesbianism is the best tool to do so because it “opens onto another dimension of the human,” beyond these pre-ordained categories. Lesbianism is a standpoint from which we can question heterosexual culture and its attendant structures, especially how these systems impact women.

Such proposals are thought-provoking and incisive, and Wittig stands quite firmly in her positions. Of course, her work – and in particular, this essay – has triggered much criticism over the years. In Clare Whatling’s article about utopia, she questions who Wittig leaves out within her (implicit) definitions of lesbian and heterosexual. Whatling brings up lesbians who are with men for economic reasons and bisexuals as people who don’t fit in her dichotomous matrix. She’s especially concerned with the consciously gendered performances of butch-femme couples, arguing that Wittig “fails to recognize the radical effect of such a performance.”

Though the two thinkers needn’t be diametrically opposed, this brings to mind Judith Butler’s conception of gender performativity and its subversive uses. Butler has long shown an admiration for drag, which they see as a useful strategy for exposing the performative nature of gender rather than contributing to its further naturalization. Butler describes two different outcomes to Wittig’s suggestion that we move beyond sexed categories. As Butler puts it, “On the one hand, Wittig calls for a transcendence of sex altogether, but her theory might equally well lead to an inverse conclusion, to the dissolution of binary restrictions through the proliferation of genders.” Both results would yield radically different worlds, though which is more revolutionary and expansive is up for debate.

Either way, Wittig’s radical theories have the ability to inspire new, inventive ideas about the future. Whatling concludes by discussing how Wittig’s work might aid in the creation of a lesbian or queer utopia. “The dream of the innumerable, the desire to break out of or at least tear a hole in the mindwarp engendered by fidelity to the category of sex is what counts,” she writes. Here we might recall B. Ruby Rich’s definition of New Queer Cinema, particularly her analysis of the difference between lesbian and gay filmmakers within this movement. “Where the boys are archaeologists, the girls have to be alchemists,” Rich writes.

In his article “Becoming lesbian: Monique Wittig's queer-trans-feminism,” Kevin Henderson suggests that Wittig’s work can be used to inspire queer critique and create coalitions among queer folks, trans people, and feminists. Henderson brings in the concept of agonism, which describes the positive aspects of conflict. “Monique Wittig’s lesbian materialism, as antifoundationalist, invites queer-trans-feminists to think about connection across supposed difference,” he writes.

Henderson defends Wittig against some of her critics, including Butler. He notes that Butler cites Wittig just as much as Foucault in their groundbreaking book Gender Trouble. Moreover, Wittig’s essay, which was written in the 1970s, proves that Butler was not the first person to “critique the category woman.” In later years, Butler would come to soften their position on Wittig. In a 2007 journal article, Butler writes that “Wittig posits a world in which the lesbian can become a figure for universality, where a lesbian’s life can be a figure for life itself, her desire a figure for desire itself, her cultural predicament a key to the understanding of culture.” The lesbian upends the assumption that men/the masculine is the origin of all things. Where does she come from?

This sort of poetical conjuring resonates with some of the ideas coming out of trans studies. As Henderson writes, “One of the promises of transgender theory is to eradicate socially imposed boundaries and move people away from ‘an unchosen starting place’” (Susan Stryker). Wittig’s work similarly seeks to abolish sexed and gendered categories that tie individuals to a primordial origin with no substance. Creating conditions of being that exist and emerge from elsewhere – perhaps from locations we can’t yet imagine – is one of Wittig’s primary objectives, and it aligns nicely with some of the ideas circulating within trans studies and among trans folks more broadly.

Henderson finds Wittig’s theories useful for the same reason that Whatling does – they point toward the potential of utopia. As Henderson puts it, “Wittig’s not-woman lesbian offers feminist, queer, and trans theorists valuable coalitional imaginaries, intellectual affinity, an opportunity to articulate and enact life, the body, belonging, desire, and struggle anew.”

Indeed, whether you agree with Wittig's ideas or not, her writing asks the reader to imagine something that doesn’t yet exist. Such is the predicament of theory. We must first learn to interpret the text, and then comes the difficult task of enacting or transforming these theories in a material sense. Witting brings us an understanding of how lesbians are positioned within – or outside of – society, but what to do with that knowledge is up to us.

We are left with a choice between assimilation and refusal, a choice that has divided queer folks for decades. Gay as in ‘happy’ or queer as in ‘fuck you?’ Maybe there’s a third option – lesbian as in transcendent.

Loved this write-up! Years ago, Wittig’s work was foundational for me as I began to understand myself as a non-binary lesbian moving through the world. Her writing helped kick start the process of languaging my experience and that was so personally liberating. Later, reading Audre Lorde’s work brought it all together for me at the intersection of being a Black non-binary lesbian. Excited for more fellow fruits to discover Wittig through this substack piece if they haven’t yet! Thank you for writing it!