This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription*** for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet and monthly playlists.

*** This is my plea to you today. Journalism is in a pretty bad state right now due to the mess that is late-stage capitalism and the trend toward AI-driven content. (Paging Dr. Lesbian does not use AI!!!) If you’re able to spare a few dollars, it would mean a great deal to me if you could upgrade your subscription. I’d like to keep this newsletter going for as long as I can, and I can only do that with your support. I might even have some extra stickers to send you if you subscribe soon. Thanks!

– Sincerely, a human, not a robot

Freudian theory may not seem like the most modern, accessible form of analysis, but within queer theory, everything old is new again. Philosophers and cultural critics have long used Freud’s concepts to define contemporary phenomena that the man himself may have overlooked. We probably have Freud to blame for the current fascination with Daddy (or Mommy) issues – ever heard of the Oedipus complex? For better or for worse, his ideas are here to stay, and queer theorists have taken that as a dynamic challenge rather than a hindrance.

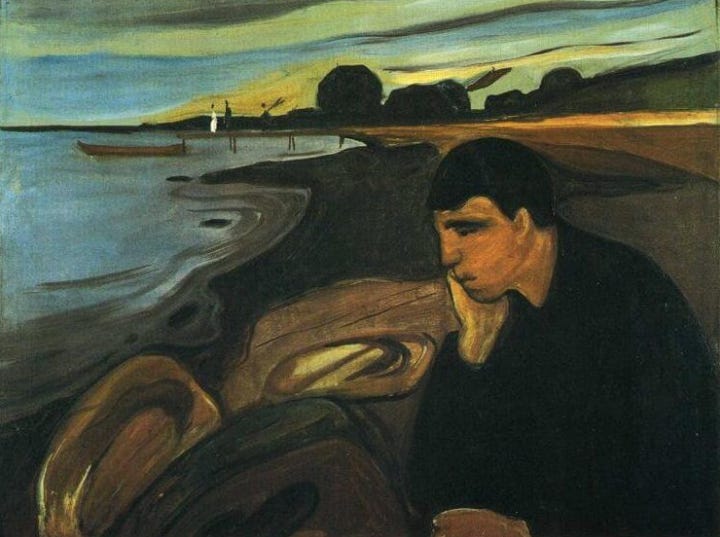

The topic we’re going to tackle today is melancholia, or melancholy. One of the most famous re-workings of the term comes from Judith Butler, the scholar who gave us the influential theory of gender performativity. In “Melancholy Gender—Refused Identification,” Butler explores Freud’s distinction between mourning and melancholia. Initially, Freud supposed that mourning was a productive response to loss that allowed the bereaved to let go of the lost object. In contrast, melancholia was an “unfinished process of grieving” wherein the subject refused to let go of what they had lost. Freud later reversed his position, admitting that “melancholic identification” – ie. incorporating the lost object into the ego itself - may be a necessary step in the process of letting go. The subject is able to accept the loss of the object in the material world by incorporating it into their inner world.

This may seem pretty straightforward so far, but Butler contends this melancholic identification also defines one’s gender and sexuality. Butler argues that both heterosexuality and normative genders are defined by a double disavowal. Heterosexuality is achieved by forsaking the possibility of queer or same-sex attachment and, secondarily, refusing to acknowledge this renouncement as a loss. “This "never-never" thus founds the heterosexual subject, as it were; this is an identity based on the refusal to avow an attachment and, hence, the refusal to grieve,” Butler writes.

Masculinity and femininity are formed based on these prohibitions. “The straight man becomes (mimes, cites, appropriates, assumes the status of) the man he "never" loved and "never" grieved; the straight woman becomes the woman she "never" loved and "never" grieved,” as Butler puts it. This adaptation of gender identity is the embodiment of heterosexual melancholy – the “loss” of queer attachment is incorporated into the ego through the formation of masculine or feminine genders. This gendered embodiment preserves the queer attachment that has nevertheless been disavowed as such.

This process has serious implications for how we define a “grievable life,” as Butler puts it in Frames of War. One of the most damning examples of the hierarchy of grief emerged during the AIDS crisis, when victims of AIDS were not seen as worthy of public grief. (AIDS activists challenged this hierarchy, generating some of the most moving public demonstrations in the history of our nation.) In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Sarah Ahmed puts it like this: “Heterosexual culture, having given up its capacity to grieve its own lost queerness, cannot grieve the loss of queer lives; it cannot admit that queer lives are lives that could be lost.”

Queer people are seen as failed heterosexuals (rather than the other way around), and as such are not permitted the same space as their heterosexual counterparts. This challenge can spark a certain kind of radical creativity. bell hooks once described queer as “being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.” Searching for new forms of queer existence can mean opting out of the hierarchy.

Though an obvious response to this division might be a repudiation of heterosexuality altogether, Butler warns against a simple reversal of discourse. They write that there is a danger in a queer disavowal of heterosexuality, which produces its own sense of melancholia. Desire needn’t be fueled by repudiation or framed by an oppositional identity. Instead, Butler suggests that risking incoherence may be the best way forward. “We are made all the more fragile under the pressure of such rules, and all the more mobile when ambivalence and loss are given a dramatic language in which to do their acting out,” they conclude.

This ambivalence plays out through performance in an influential work from one of Butler’s peers, the late José Esteban Muñoz. In Disidentifications, Muñoz describes a process by which minoritarian subjects resist the forces of normalizing identity discourse while at the same time incorporating some of these identity structures into their persona. It is a means of survival that involves rejecting reductive ideas and reframing those that can be useful. This sort of identity collage is necessarily disordered and exemplifies the kind of incoherence that Butler privileges.

Muñoz, too, describes a form of melancholia that expands beyond Freud’s original formula. While Freud marked melancholia as pathological and saw mourning as the preferred grieving process, Muñoz rejects this division. “I have proposed a different understanding of melancholia that does not see it as a pathology or a self-absorbed mood that inhibits activism,” he writes. “Rather, it is a mechanism that helps us (re)construct identity and take our dead with us to the various battles we must wage in their names – and in our names.”

Muñoz formulates a combination of mourning and militancy, a posture first defined by art historian and AIDS activist Douglas Crimp. Muñoz’s melancholia is “identity-affirming” and leans into the “ambivalence of identification” that pervades minority communities. Ahmed chimes in with her own definition of a community-oriented melancholia. “To lose one another is not to lose one’s impressions, not all of which are even conscious. To preserve an attachment is not to make an external other internal, but to keep one’s impressions alive, as aspects of one’s self that are both oneself and more than oneself, as a sign of one’s debt to others,” she writes.

While a commitment to embodying loss might seem like a form of queer negativity (rather than the ruling position, queer positivity), Muñoz and Ahmed argue that queer melancholia is a progressive stance that brings the past with us. Whereas Butler illustrates how heterosexual melancholy produces both a hierarchy of life and a hierarchy of grief, Muñoz introduces queer melancholia as a way to make loss visible.

Culturally, we seem to be turning away from tragedy, especially when it comes to how we want to see ourselves as queer people. In Feeling Backward, Heather Love writes, “Resisting the call of gay normalization means refusing to write off the most vulnerable, the least presentable, and all the dead.” Acknowledging loss means recognizing the ties that bind us and resisting the urge to sever connections in order to bolster our own personhood. Risking incoherence, as Butler puts it, is worth it if it brings us closer to one another.