This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe!

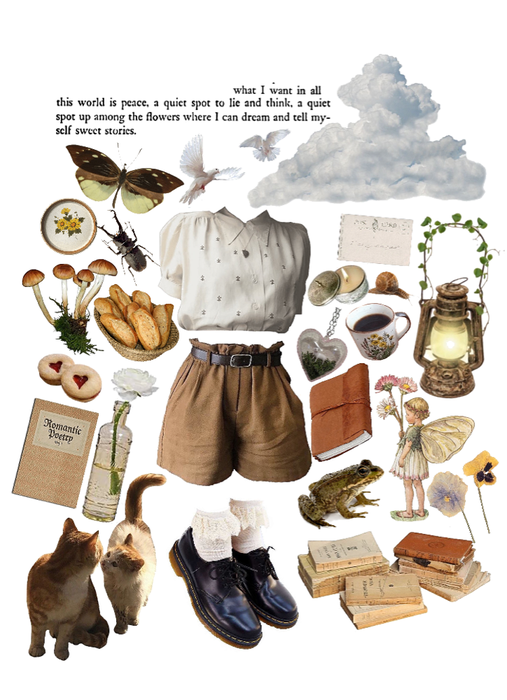

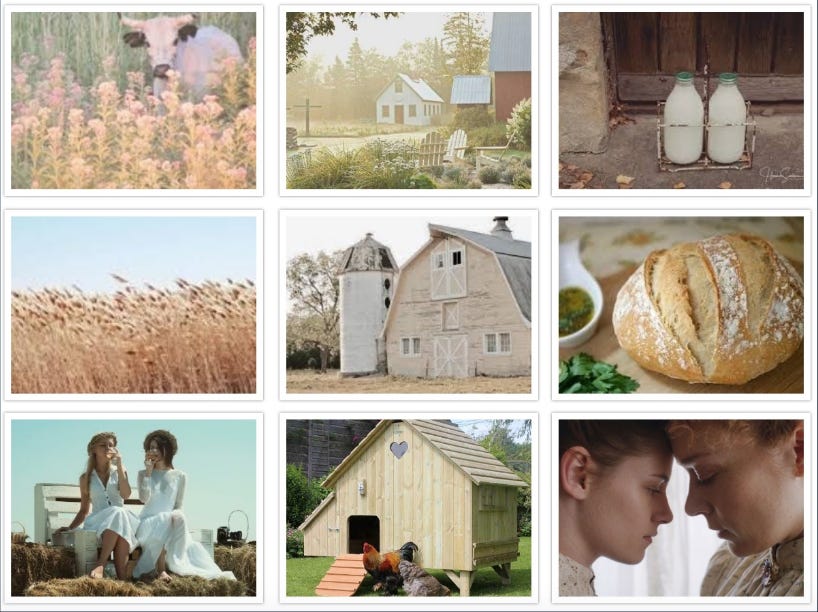

If you’ve been Extremely Online during the pandemic, you may be hip to a recent aesthetic/lifestyle trend that has taken the internet by storm over the last year – cottagecore. The term has become so popular that it has been reported on in publications such as The New York Times, Architectural Digest, and Vox. Describing the trend to AD, Davina Ogilvie says “as a concept, it embraces a simpler, sustainable existence that is more harmonious with nature. Aesthetically, it’s a nod to the traditional English countryside style, romantic and nostalgic.” The subreddit r/cottagecore defines it as “an aesthetic depicting a simple, romanticized life in nature. It features themes of farm animals, earthy tones, soft illustrations, and more.” According to Know Your Meme, who I trust with all things, the earliest #cottagecore post on Tumblr can be traced back to 2018, but the idea became even more popular in 2019 thanks to Tik Tok, and increased in popularity once again in 2020 thanks to the circumstances we all found ourselves in during the pandemic.

Talking to Vox, a trend expert at Tumblr noted that “from early March to early April [of 2020], the cottagecore hashtag jumped 153 percent, while likes on cottagecore posts were up 541 percent.” Baking sourdough from scratch is in fact a very #cottagecore thing to do. Then we had Taylor Swift’s folklore (and later evermore), which is probably the most cottagecore-like album to be released since the term was first coined. (Her performance at the Grammys, during which she performed inside a literal cottage, only solidified this connection).

From the imagery this idea presents – an agricultural, DIY, analog, often feminine aesthetic – it might be difficult to easily decipher the particular social or political leanings of its fans or practitioners. As Isabel Slone puts it in the New York Times, the movement is not as conservative as one might think. “Unlike reactionary movements like “trad wives” — essentially right-wing mommy bloggers who advocate a return to regressive gender roles — cottagecore offers a vision of domestic bliss without servitude in the traditional binary framework.” Indeed, the concept has been taken up most passionately by a group that has claimed cottagecore as their own: lesbians.

If you, like me, spend a lot of time thinking about lesbian culture and aesthetics, this seemingly inane connection might actually make sense to you. There are numerous aspects of cottagecore that align nicely with various facets of lesbian culture. One of these ideas is the concept of longing, which has long been understood as a particularly queer feeling. (I’ve written about it myself). As Rebecca Jennings puts it in Vox, “Cottagecore is less about a lifestyle and more about the longing for it, the yearning that maybe things would feel different if they looked a little prettier.” This longing brings up another important point about cottagecore – many of its followers do not literally live the cottagecore lifestyle, but rather long for the type of magical calm it seems to provide.

Various interpretations of the cottagecore lifestyle abound on places like Tik Tok and Tumblr, many of which reference certain pop culture artifacts that have now been labeled as cottagecore canon. One popular Tik Tok, when your mom says you can’t decompose in the damp grass with your girlfriend, depicts a young woman slamming the door to her room and blasting Hozier when her cottagecore dreams are vanquished. Hozier (who is also a canonically lesbian artist), features prominently in cottagecore lesbian content, particularly the song “In A Week” (referenced in the aforementioned Tik Tok), which is literally about decomposing in nature. Also popular with cottagecore lesbians is the British singer and YouTuber Dodie, whose song “She” (which contains the lyrics “she smells like lemongrass and sleep / she tastes like apple juice and peach”) is also featured in several Tik Toks. More recently, popular lesbian singer Hayley Kiyoko released a music video for her song “Chance,” featuring what is probably the most cottagecore lesbian aesthetic I’ve ever seen in a music video. (For a more extensive cottagecore lesbian musical experience, check out this popular cottagecore lesbian Spotify playlist).

Other popular cottagecore lesbian pop culture artifacts include Miss Honey from Matilda (frequently called the “original cottagecore lesbian” and also the object of many sapphics’ pre-pubescent desire), Willow and Tara in the musical episode of Buffy, and various characters from Miyazaki movies. I’ve also seen gifs of the lesbian period piece The World To Come tagged as #cottagecore on Tumblr, which though technically a valid categorization, is also confusing because that movie is depressing as hell. (The far more cheerful Summerland, which I’ve also seen included in this category, is, in my opinion, a better choice for that particular fantasy). Other supposed examples of cottagecore lesbians include Brandi Carlile and her family (who live on a rural commune) on the cover of Parents Magazine as well as the new Cottage Living Sims expansion pack, which will allow users to create their very own cottagecore lesbians.

One of the most intriguing objects in cottagecore lesbian culture is one I wasn’t expecting to encounter so much: frogs. Frogs, it seems, have become the de-facto mascot for cottagecore lesbians, and images of them seem to pop up everywhere when you search for the term. I imagine this has something to do with the inherent cuteness they possess, as well as the prior distaste for frogs (or at least toads) that this newfound adoration seems to consciously push against. (Lesbians love to take things that were once considered ugly or uncool – see: mullets and Hawaiian shirts – and reclaim them). Like mushrooms – another popular image – they are easily conceived of as adorable and help to set the scene for what a cottagecore lifestyle might look (and sound) like.

I think there are also deeper, more personal reasons why cottagecore resonates with lesbians so much. For cottagecore lesbians, this idealized lifestyle represents a feeling of safety that is uniquely alluring. As Rowan Ellis puts it in her video “why is cottagecore so gay,” “for queer and sapphic women, [cottagecore] allows them to imagine a space without homophobia, fear and judgement, that doesn’t feel like a banishment but instead a specifically curated paradise.” As I mentioned earlier, there is a particular kind of longing present here that highlights how cottagecore is all at once an aspirational lifestyle, an aesthetic, and a feeling. If it had to be put into words, I would describe this feeling as soft (another important concept in sapphic culture), which, as is cottagecore itself, is a reaction to the otherwise hard modern world.

For cottagecore lesbians, romance is also an important part of the fantasy. Part of cottagecore is an aesthetic, sure, but part of it also seems to be a sense of longing for romantic happiness that coincides with this bucolic setting. Certainly, there seems to be a contradiction here that this yearning for a simple – and assumedly pre (or post) digital – life exists primarily on places like Tik Tok and Tumblr, but then again, there really is no other way to consume this fantasy when you’re not yet living it. (And, to be sure, being rural is not the same as being off-line). Indeed, for lesbians and other sapphics, the internet has long been a place to find potential romantic partners (even before the market was saturated with dating apps), and it’s not like these countryside cottages come with a girlfriend pre-attached.

There’s also a sense that the stressors of modern or urban life magnify a lot of the mental health issues that queer people often struggle with. You might see someone online saying “If I lived here [insert cottagecore dreamscape] I wouldn’t have mental illness.” While comments like these are most of the time at least slightly sarcastic, there does seem to be an overall sense that at least some of the problems of the contemporary world would be solved if we all just lived in cottages surrounded by frogs.

There also seems to be a sense of connection between the cottagecore of today and the rural lesbian endeavors of the past. As Ro White notes in Autostraddle, cottagecore “hearkens back to the withering lesbian separatist movement of the 70s” wherein lesbians strived to create their own communities apart from the structures of patriarchy and capitalism. As White suggests, one difference between these two movements is that “cottagecore is more focused on the individual (running away to the woods with your girlfriend) than the collective (establishing a commune),” although there is in some sense a community-oriented element in both.

While cottagecore and cottagecore lesbians aren’t as explicitly political as lesbian separatists once were, there is an anti-capitalist thread that runs through the concept, which itself leads to particular aesthetic and lifestyle choices. These active aesthetics are in various ways rooted in some sense of lesbian culture. As Eleanor Medhurst puts it, “though lesbianism is of course rooted in loving women, other principles also exist at the forefront of a political lesbian existence: connecting with nature, hand-making and growing, craft, equality.”

The allure of the cottagecore fantasy is certainly rooted in a particular queer experience as well. As one Reddit user noted in their explanation of cottagecore’s popularity among lesbians: “You can kinda understand why getting away from civilisation and living an idealised self-sufficient life with your loved one in the woods is a fantasy for a lot of gay youth who have to deal with heteronormativity (and discrimination) in daily life. The aesthetic is calming, safe, and an escape.”

That’s not to say that the movement is without complications. There have been criticisms of this idea of a rural fantasy, particularly in the United States where the land rights of indigenous people are an ongoing issue. And while the notion of cottagecore has been purposefully expanded to include a more diverse cast of practitioners – particularly by black content creators like CottagecoreBlackFolks – this very real issue of land ownership persists. As White asks us, “Is cottagecore truly for everyone when some of us get [to] dream of “running away to the land” while others struggle to take that land back?”

Like with all trends, there have also been criticisms that cottagecore lesbians have become “too much of a thing” and are now coming to define the lesbian aesthetic. Cottagecore defenders argue that rather than being the representative of lesbian culture, cottagecore lesbians are in fact a positive force because they in part emerged as a way to combat the oversexualization of lesbians that occurs elsewhere in media. In essence, these users would argue, cottagecore lesbians represent a specifically (and purposefully) romantic antidote to a hypersexualized image.

Frankly, it’s unclear if those involved in digital cottagecore lesbian culture would actually want to live the lives they fantasize about online. (Indeed this is another critique of the concept, even one made by cottagecore fans themselves). It does seem that cottagecore lesbians do actually exist offline, and it can be exciting to see them IRL. One overjoyed Reddit user shared that they “just saw two cottagecore lesbians on a picnic at a park by my house!” as if spotting a mythical creature in the wild. But, regardless of whether this trend continues to expand beyond the confines of the internet, cottagecore has been claimed by lesbians, which is enough to keep it alive for now – maybe forever. (Just like the mushrooms in Miss Honey’s garden).