This is the Sunday edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. Plus, this week’s dispatch from the lesbian internet. If you like this type of thing, subscribe!

If you have any awareness of Film Twitter, or online film culture more broadly, you’re probably familiar with the film cataloging site Letterboxd. Letterboxd was first launched in 2011 and is similar to a site like Goodreads – it’s a space where users can log all the films they watch, and if they so choose, rate and review them. Like Goodreads, there is also a social media aspect to the platform, as users can follow each other and comment upon one another’s reviews.

For this week’s issue, I spoke with Lucy May, (known online as “Letterboxd Lucy”) one of the most popular users on the site. I asked Lucy about how Letterboxd functions within film culture specifically as well as how she sees the site intersecting with online queer and sapphic culture more broadly.

As of this writing, Lucy has more than 63,000 followers on Letterboxd and is the second most popular user on the site, as defined by Letterboxd’s own popularity metrics. (The most popular user on the site logs films under the username bratt pitt – but goes by Mia elsewhere – and her review of Fight Club also holds the distinction of being the most-liked review on Letterboxd). Along with being a popular Letterboxd user – her Twitter bio reads “accidental film critic and Letterboxd clown” – Lucy is also a video editor, and posts masterfully-edited year-in-review videos on her Vimeo and reviews on her YouTube channel. She has been on the site since 2014 and has been using it to log every movie she has watched since.

Like with many online spaces, the social dynamics of Letterboxd are complicated, and the most toxic elements of the site are rife with misogyny and homophobia. Though the site is populated by some “mainstream” film critics (Indiewire’s David Ehrlich is another popular user), many of the top users on the site are young queer women like Lucy and Mia who are either working their way up in the industry or just using the site for fun and community. I asked Lucy why she thinks so many of the site’s most popular users are queer women, and she agreed that it was a definite trend. “Perhaps it’s because in the past it seemed that many spaces to talk about film were usually occupied by men, especially cis straight white men, who shared similar ideals about what makes a good film or what makes a bad film,” she says. “With the growth of new spaces on places like Letterboxd and Twitter, I think many younger and diverse users flock to critics and film fans that they see themselves in.”

Unfortunately, a lot of the women who are most popular on the site get a certain amount of hate for their reviews, which their critics see as an example of “bad taste.” Some of this is because many Letterboxd users frequently post joke-style reviews rather than what might be called “serious film criticism.” Lucy, for her part, sees the freedom Letterboxd allows for to be a benefit of the site: “Whether I feel like making a joke or taking my time to gather my thoughts in a deep dive analysis is my call depending on the film and my mood.”

Indeed, Lucy’s reviews often have a humorous bent to them, but can also take a more serious or personal turn (her heartfelt review of the film Run was actually noticed and applauded by the film’s director). Women like Lucy often get hate for negatively reviewing films typically loved by Film Bros (see: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood or The Joker), or, on the other hand, for celebrating female-centric films often derided by these same fans (for example, Captain Marvel or Jennifer’s Body).

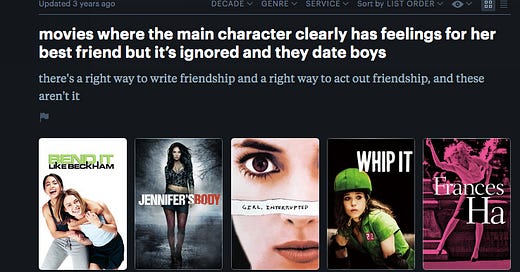

These Letterboxd “purists,” if you will, (read: haters) feel that the site should be used for “serious” reviews rather than the light-hearted jokes that popular users like Lucy often post. Half-serious hyperbole is common on the site – you might find a user saying Jennifer’s Body “invented feminism” or that Charlie’s Angels “made them gay” – and this type of language seems to particularly rile such formalists. (One time a random man commented “SHUT UP!!!” on my effusive review of Janelle Monae’s Dirty Computer for reasons that are still a mystery to me). But one of the things these poor sports (read: misogynists) forget about this site is that as much as it is a film blogging site, it is also modeled and used as a social media site – a platform for people to discuss their hobbies and share the things they love (or hate). As Lucy puts it, the site has become a way to “digest” film, and its diary function makes this activity a more communal one. The platform’s “list” function (pictured below) also gives users another way to categorize and track the films they watch or seek out new ones.

Lucy told me that while it can be stressful to have such a large following online, she has ways of dealing with it – namely, taking a step back from social media when things get too stressful. But Lucy also knows that many of her followers almost feel like they know her personally despite having never met her, (hence the nickname), and tries to respect these relationships that she has unexpectedly built: “Overall I hope I come off as nice and approachable because I see many of the people that interact with me as friends in a way, so I try to respect them as such and I think it often makes the internet kinder and more fun to use that way.”

When you really think about it, it’s actually quite inspiring that a site like Letterboxd – which in and of itself is a part of the previously male-dominated world of film criticism and film culture – has become a space where women, and in particular queer women, have found some modicum of success and visibility. As Lucy puts it, “it’s almost like we’re all carving out a new and more inclusive space together.” Indeed, there is a sense among users that this notion of representation and visibility is important and affirming, even on a casual blogging platform like Letterboxd. As Lucy sees it, this trend is exciting, and incentivizes her to be more honest in her reviews: “[I] try to wear my heart on my sleeve in the way that I write so that other women, members of the LGBT community or even people with disabilities can see a little of themselves in what I write and how I look at film.”

In this vein, it can feel exciting and affirming to be on a site like Letterboxd and see yourself reflected in the language and the humor found therein. Understanding a particular type of humor is one of the things that can make one feel most connected to a specific group or community, as jokes have the effect of demarcating those who are “in” on the joke and those who are not. “There’s a certain bond and sense of humor I’ve found that connects me with other lesbians, bi women, and sapphics that even extends to my reviews in terms of inside jokes or references,” Lucy says. But being able to comfortably display this humor in front of others can take time, as well as confidence, and that doesn’t always come easy. “It’s taken me a long time to be comfortable enough with myself and my sexuality to connect with others in the community and I really cherish it now as part of my daily life,” she continues.

As with all social media sites, Letterboxd is something like a microcosm of our culture at large, amplifying both the most promising and the most toxic elements of modern life as they exist online. And while it is unclear if Letterboxd will fundamentally change the nature of film criticism or movie-watching, Lucy is hopeful. “The site normalizes conversations about arthouse and non-English films, makes it easier to find hidden gems, and can even bring more respect to previously ridiculed genres like romantic comedies,” she says. Despite some of the site’s more pernicious elements, it has also become a space where young people, and in particular young sapphics, can express their interests and their points of view in a way that allows them to find others like them. And while some others may not agree with their methods – Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle (2003) still has a downright disrespectful average rating of 2.6/5 on the site – the sapphics of Letterboxd are here to stay.

You can find Lucy on Letterboxd, Twitter, Vimeo, and YouTube.

Welcome to this week’s dispatch from the lesbian internet.

I have nothing else to say about the Meghan Markle / Oprah interview that hasn’t already been said (read this from Doreen St. Felix), except for this:

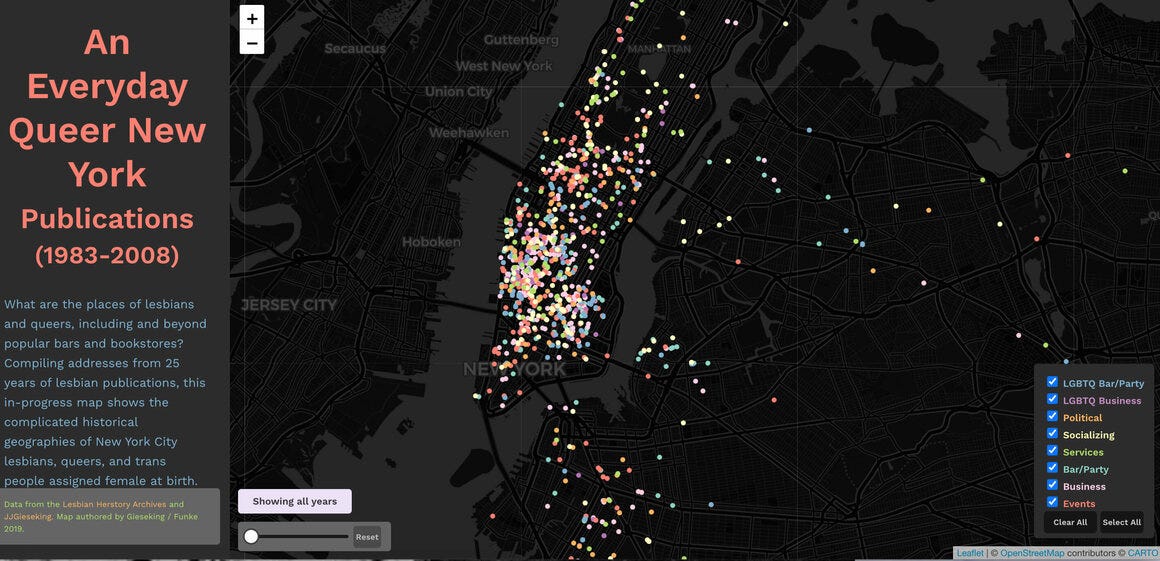

Speaking of lesbian bars, On Tuesday I read about a new interactive tool that maps 25 years of queer social life in New York City. The tool is part of a larger project by Jen Jack Gieseking, an Assistant Professor of Geography who is trying to map lesbian, queer, and trans social spaces in New York City. Lesbian bars notoriously have a high turnover rate, in part because queer women and trans people on average have significantly lower incomes than their cis male counterparts. Interestingly enough, Gieseking found that some of the hottest spots for sapphics and trans people were not bars at all: for example, the Park Slope Food Co-op was frequently cited as a place to catch up on gossip, as was a local Trader Joe’s. Check out a snapshot of the map below.

On Wednesday it was Sharon Stone’s birthday, which obviously made me think of one of the most riveting films of all time, Basic Instinct. I am thinking about Stone’s Catherine Tramell always. Please enjoys these images of Catherine and her little girlfriend Roxy from one of my favorite Instagram accounts.

On Thursday, Glamour published a profile of Demi Lovato that focuses on her struggles with sobriety and disordered eating as well as her new perspective on sexuality. While Lovato has discussed her attraction to women in the past (she was rumored to have dated DJ Lauren Abedini), this interview reveals her more recent feelings on the subject. After breaking things off with her fiancé last year, Lovato says she now feels “too queer” to be with a cis man right now. “I hooked up with a girl and was like, ‘I like this a lot more.’ It felt better. It felt right,” she says. (In other news, some people think the girl in question was none other than Miley Cyrus). Anyways, more power to her!

That’s all for this week, folks! Stay tuned for next week’s deep dive. I will leave you with this powerful image of Sharon Stone and Halle Berry in the seminal Catwoman (2004).