This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet, monthly playlists, and a free sticker.

What does it mean to write a gay child in a film? No matter the answer, the question itself has people up in arms. Many have strong opinions about kids being “exposed” to gay media, not to mention media where the kids themselves might be coded or explicitly portrayed as queer.

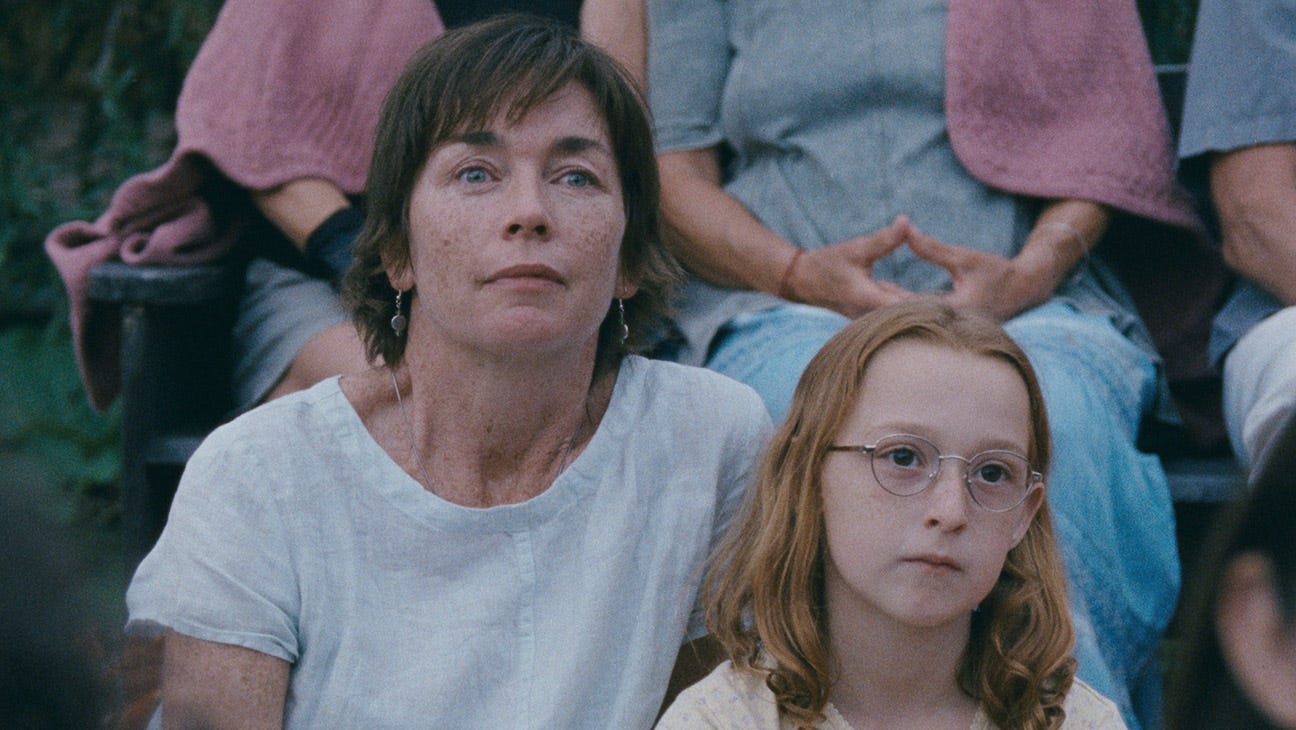

Annie Baker’s first feature film, Janet Planet, follows a girl and her mother. Janet (Julianne Nicholson) is a captivating woman, attracting those around her yet remaining at a distance from most. Her daughter, Lacy (Zoe Ziegler), is a strange, solitary child who wants to be as close to her mother as humanly possible. She wants to possess her, in a way, to know every single one of her thoughts and feelings.

In the first scene of the movie, Janet calls her mother to pick her up from summer camp, convinced no one there likes her. Her suspicions are proven wrong as she’s packing up to go, but it’s too late. Her mother arrives to come get her, and their summer together – in which three different figures move in and out of Janet and Lacy’s lives – begins. It’s 1991, and Lacy is 11 years old. The summer before she starts middle school will prove to be an illuminating one.

Lacy is odd, and her behavior is sometimes off-putting. She also may be queer. The film itself seems to confirm this fact – or at least this inkling – during a conversation between mother and daughter. Lacy wonders if she might date a woman when she grows up, and Janet reveals that she has considered that possibility before. Lacy has a unique presence, and Janet has trouble imagining Lacy’s formidable energy melding with that of a man.

Janet Planet is not a typical coming-of-age story, nor is it a typical queer story. There’s no adolescent romance or any sense of burgeoning sexuality. There are no bullies for Lacy to stand up to, nor any tangible obstacles for her to overcome. (Though she tells her mother at one point that “life is hell,” there’s not any one thing that’s making her feel this way, at least not that we can easily perceive.)

Still, despite the absence of these classic benchmarks of growing up and coming into one’s self, Lacy reads as a queer kid. But how can this be so, when there is no romance to speak of? Janet Planet is not the only film to suggest that kids can embody and experience queerness in a manner that doesn’t revolve around romantic love or sexual attraction.

The Disney film Luca, which was widely read as a queer story despite the director's refusal to name it as such, is one example. The title character is a sea monster who decides he wants to be a part of the human world. He meets another sea monster, Alberto, who teaches him how to navigate this new environment. His parents worry the humans will reject him – society literally sees him as a monster – and he’s afraid of revealing his true nature to the townsfolk. The movie tells a quite literal coming-out story, not to mention Luca’s life-affirming friendship with Alberto. Though Disney refused to discuss the film in queer terms, queer viewers have overwhelmingly read it in such a way, and for good reason.

In Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun, the child protagonist is confirmed as queer, though queerness isn’t, at least on the surface, the primary preoccupation of the film. Set in the late ‘90s, the film follows Sophie (Frankie Corio), an 11-year-old on vacation with her young, depressed father (Paul Mescal). In a brief scene set in the present day, we see adult Sophie living with another woman. But other sequences in the film point to Sophie’s queerness as well, such as the scene when she witnesses two boys kissing and finds herself intrigued, if not in a state of revelation. This moment of recognition is part of Sophie’s queer journey, one that doesn’t yet involve romance, but concerns the process of working out how to engage with the conventional stepping stones of adolescence.

In Janet Planet, the conversation between Janet and Lacy is the most obvious suggestion of queerness, but there are other moments, too. Lacy understands that she doesn’t quite fit in, and she expresses a sense of disconnection from the world and the people around her. She’s happy enough with her mother and with her keyboard, but she possess a deep sense of longing. For what? That seems difficult for Lacy to put into words. It’s the ‘90s, and Lacy lives in rural Massachusetts, so it's unlikely she’s been exposed to much language or many images of queerness. Still, these affinities persist.

When attempting to parse out the meaning of a film or its characters, one might turn to its authors. But does authorial intent matter? The director of Luca, Enrico Casarosa, contends that his film isn’t gay because it’s prepubescent and also “pre-romance.” His argument that the relationships in the film are “only” friendships and thus not queer negates the film’s entire plot, which is, whichever way you slice it, about being queer in a straight world. (Not to mention the fact that friendships can certainly be queer even if they’re not sexual.)

Aftersun director Charlotte Wells takes the opposite approach in terms of intentionality. “My characters are always going to be queer by default,” she told the LA Times. Of course, you needn’t agree with Wells’ presumption, but her statements give the viewer permission to read queerness into her characters even if such details aren’t explicit. For example, many have understood Paul Mescal’s character in Aftersun as queer, which adds deeper meaning to his inner turmoil. In this instance, queer viewer and queer director find themselves on the same page.

Like Casarosa, Baker argues that it was important to make the story not about puberty or the onset of sexuality. “I wanted to capture something else about a kind of intellectual, spiritual development happening for a little girl that I’d actually seen in a lot of movies about boys,” she shared in an interview at the New York Film Festival. Still, Baker never suggests that this pivot is antithetical to the experience of queerness (though she doesn’t explicitly make this connection either). If Lacy’s summer teaches her something about the world of adults and her place within it, might she also come to find her queer bearings?

Casarosa and Baker’s takes on child development bring up the question of whether adolescent queerness can indeed be divorced from puberty. In these films, queer childhood is not a matter of sexual maturity or the science of attraction. Instead, it’s a temporarily ineffable sensibility, a way of existing in and looking at the world, a feeling of difference or not fitting in. It’s not seeing yourself in the future that’s expected of you. This still rings true today, but is perhaps more acute for these young characters living in decades past.

Reading Lacy as queer is not so much an intellectual exercise as it is a feeling of resonance. She is such a compelling character because you’re invited to see the world through her eyes, putting aside adult concerns for a moment to delight in curiosity. Some viewers may feel more connected to Lacy than others, but that invitation remains. Lacy seems to already have a sense that she might be queer, but even if she never voiced that, her relationship with the world around her still resonates in this way.

Such is the potential of cinema, and the power of queerness as a lens. Film has the ability to affect the viewer, to inspire reflection and introspection. A queer lens, as embodied by a film or by a character, can be probing, expansive, and hold up a mirror to the world around it. To place this critical lens in the hands of a child, already the most curious and inquisitive of us all? It’s a moving project, no doubt. May we all find time to open ourselves up to queer possibility.

girlkisser here, girlkisser there, girlkisser everywhere

Do gays deserve awards? Have baby mamas ever looked so beautiful? Is Sophia Bush creating sapphic chaos on network TV? And other questions.