This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. A paid subscription gets you more writing from me and will help me keep this newsletter afloat. Consider going paid!

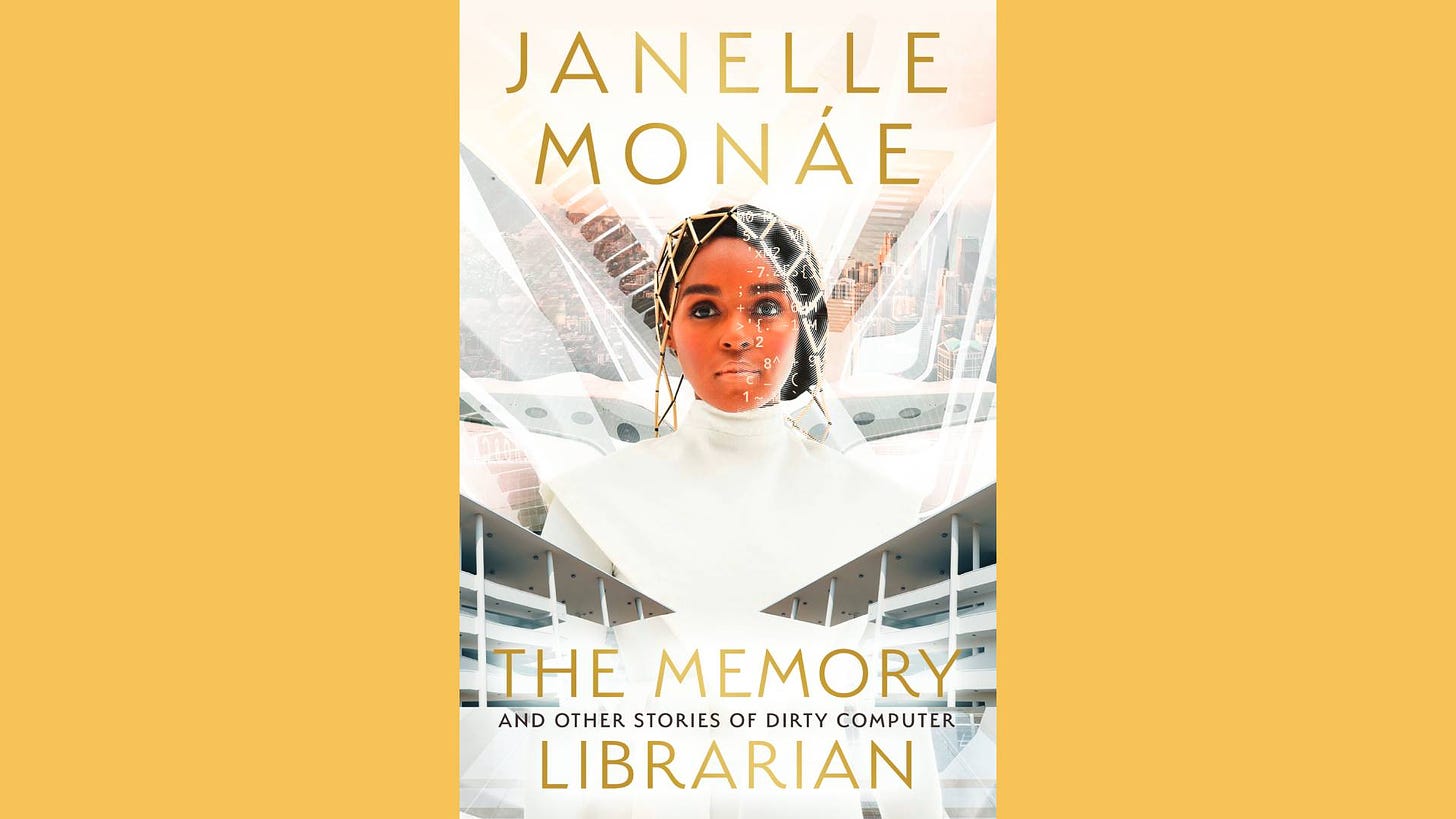

On her 2018 album Dirty Computer, musician and actor Janelle Monáe sings “I’m not America’s nightmare, I am the American dream.” The album, along with the accompanying “emotion picture,” depicts a dystopian world where those who don’t fit the norm – known as dirty computers – have their memories wiped by New Dawn, an organization that works to maintain this new world order. Monáe’s new book, entitled The Memory Librarian, further explores the world she first envisioned in Dirty Computer, expanding the scope of the story. These two projects aren’t the first time Monáe has engaged with these themes of science fiction and Afrofuturism, however. For that, we’ve got to go back even further.

Monáe has been exploring these ideas for over a decade now. Her first EP, Metropolis: The Chase Suite, is the first installment in a three-album series that follows an android named Cindi Mayweather. Made to be bought and sold for human consumption, Cindi falls in love with a human and is then sentenced to disassembly. In the events that follow, Cindi becomes a messiah-like figure and is sent back in time to free the people of Metropolis from an evil group known as the Great Divide, who use time travel to suppress people’s freedom and ability to love. Following the initial EP, Monáe released The ArchAndroid and Electric Lady, the second and third installments of the series.

Much of Monáe’s work makes very clear references to science fiction works of the past. Most obviously, Monáe’s Metropolis series is inspired by the 1927 film of the same name, directed by German filmmaker Fritz Lang. Considered one of the most important films ever made, Metropolis is set in an urban, dystopian future and looks at the struggles of the working class. The film follows Freder, the son of an industrialist, and Maria, a young woman who cares for the workers’ children and attempts to initiate a revolution. Fearing Maria’s power to inspire the workers, the industrialists create a robotic look-alike version of Maria which they use to quell the workers’ desire for revolt.

The robotic version of Maria – and her position as a false prophet – is a significant point in both Monáe’s Metropolis series and Dirty Computer. Both projects depict robots or robot-like humans who have the power to placate the masses but also the power to free them. Of course, it’s only the real Maria who is able to inspire the revolution after all, as she has the heart her robotic counterpart does not. The quote from Metropolis that most inspired Monáe’s project was the final title card of the film, which reads: “The mediator between the hand and the mind is always the heart.” Whether human or synthetic, the heroes in Monáe’s world are always defined by their capacity for love.

It’s easy to make comparisons between Monáe’s work and the writings of Octavia Butler, a science-fiction author often associated with the philosophy of Afrofuturism. Butler’s work frequently addressed what she saw as one of humanity's greatest flaws – our tendency towards hierarchy – and her writing often looked at the manipulation of the human body. This biological evolution is both literal and metaphorical, and for Butler, was often a necessary development in the march towards undoing hierarchy. Butler’s work contended that this hybridity is powerful, and it isn’t something we should turn away from. Though there is a clear distinction between the “real” Maria and the “false” Maria in Metropolis, Monáe doesn’t make these distinctions as clear in her own work, echoing Butler’s penchant for unflinching complexity.

In The Memory Librarian – which Monáe co-wrote with five other authors – Monáe explores these complexities even further. If there’s one criticism that can be leveled at Dirty Computer it’s that it can be a bit disjointed at times, bringing up various themes without always drawing a clear connection between them. Thankfully, the book fills in those blank spaces, and defines the contours and the edges of the world more clearly. The Memory Librarian usefully expands on the themes of Dirty Computer, illustrating how these different viewpoints and structures interact with one another.

The first titular chapter of the book, co-written by fantasy author Alaya Dawn Johnson, follows a woman at the very center of New Dawn, the organization that now runs the United States. Seshet is the Director Librarian of Little Delta, which means she spends her time looking through the memories and dreams of the cities’ residents, on the lookout for agitators. Sheshet’s allegiance to New Dawn is tested when she falls in love with a mysterious woman named Alethia.

In the chapter “Nevermind” – which takes its name from the mind-wiping drug introduced in Dirty Computer – we get a closer look at the Pynk Hotel, the setting for the “Pynk” portion of the emotion picture. This chapter, co-written by Danny Lore, follows Jane (the character Monáe portrayed in Dirty Computer), as she leads the residents of the hotel while they face threats from New Dawn. Also present in the chapter is Jane’s lover, Zen (played by Tessa Thompson in the film), and Neer, a young mechanic.

In “Timebox,” – co-written by sociologist Eve L. Ewing – we follow Raven and her girlfriend Akilah, two young women who find a magical room in their apartment that allows them to pause time. In “Save Changes,” which features the work of Yohanca Delgado, we travel to New York City and get to know Amber and her sister, Larry. Their mother was once a revolutionary, and now lives under house arrest after a procedure to turn her into a “torch” – essentially a mind-wiped worker at New Dawn – went wrong. To make matters even more complicated, before he died Amber’s father gifted Amber a watch that can turn back time – but she can only use it once.

Though none of the stories are explicitly connected, the final chapter of the book brings everything together and offers something of a roadmap for the future. “Timebox Alter(ed),” co-written by Sheree Renée Thomas, takes place in Freewheel, a town outside the borders of New Dawn. It follows four young people who unknowingly build a mysterious portal that allows them to inhabit their dreams of the future. Having long given up wishing for something better for their community, these dreams give them the hope they need to go out into the world and change things for the better, creating futures they didn’t even know were possible. As the story suggests, in order to build a better world, you need to be able to imagine it first.

In many ways, this final story is the thesis statement of the entire project itself, and of Monáe’s work as a whole. As co-author Yohanca Delgado put it in an interview, "It's hard to feel hopeless when you're busy imagining all the different ways in which the world could be transformed.” Whereas Dirty Computer continued exploring some of the themes of Metropolis from a more personal viewpoint, The Memory Librarian expands the scope even further, giving Monáe’s imagined revolution not just one representative, but many. By focusing on characters in very different positions – from inside the belly of the beast in “The Memory Librarian,” to on its fringes in “Nevermind” – the project identifies the unique roles we all have to play in this revolution.

Despite the dystopian world that New Dawn has created, Dirty Computer and The Memory Librarian are, at their core, hopeful stories. Monáe goes beyond the catchy catchphrase “The Future is Female,” positing instead that the future will be black, queer, and trans – a much more radical dream. By collaborating with black women and non-binary writers on the project – and filling the book with black queer and trans characters – Monáe is endeavoring to realize this dream, both on and off the page. Rather than rehash tired (and misconceived) conversations about intersectionality, Monáe has instead found a way to celebrate difference without softening the edges of nonconformity.