It Doesn’t Matter What Taylor Swift’s ‘betty’ is Really About

On Sapphic Swifties and The Queer Canon

Editors note: I had originally conceived of this piece months ago when Taylor Swift had only released one surprise quarantine album. Now that she released two such albums, any writing about folklore almost seems passé. Nonetheless, I contend that this topic remains relevant, and as such I’ve chosen this piece as the inaugural edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian because I think it exemplifies many of the nuances of online queer culture, and in particular online sapphic culture, that I intend to investigate in this newsletter.

Several months ago, Vulture published an article declaring that “Taylor Swift Doesn’t See ‘betty’ As Queer Canon.” The song, which is addressed to a teenage girl named Betty, immediately captured the attention of queer swifties who seized upon its sapphic potential. While Taylor Swift did indeed finally confirm her intent with the song – it was written from the perspective of a 17-year old boy named James, which we already knew – the title of the article reveals a misunderstanding about what the “queer canon” really is. Namely, this framing of Swift’s statements about the song assumes that she has the power to define whether or not ‘betty’ is a queer piece of music. To put it plainly, the queer canon is not defined primarily by artists or media gatekeepers, it is defined by us – queer people.

The idea of a queer canon may sound like a vague concept, so let’s give it some definition. (For more on this, see my digital thesis on the subject. The video below is a visual representation of the concept which I explore more here). At its core, the queer canon is comprised of all the media that queer fans see or interpret as queer. This can include objects that are important to queer men and queer women, as well as trans or non-binary people, though I would argue that each group also has in some sense its own distinct canon. This media can be “canonically” (in the conventional sense of the word) queer media properties, like The L Word or Hayley Kiyoko, or ones that fans have interpreted as queer, like Rizzoli and Isles or Captain Marvel. These items are claimed by queer fans regardless of – and frequently in spite of – what their creators intended, and for many fans there is a distinct pleasure in collectively defining and maintaining the queerness of these objects. Indeed, one of the delights of this canon is that it can only be recognized or understood in its entirety by the queer people who are involved in its creation – for everyone else, it’s a confusing jumble of media properties that have no apparent connection. (Please find me a straight person who can find the link between the ABC series Once Upon a Time and the Taylor Swift song Dress).

Of course, this does not mean that instances of queerbaiting – when a media producer creates something that they know could or will be read as queer in order to attract viewers without any intention of actually following through – still hurt, and the relationship between queer fans and mainstream media production remains fraught. (Please do not ask me about what went on with Rizzoli & Isles, or I will start ranting and never stop).

Genuine representation of queer people is undoubtedly important. But while I would be thrilled if Captain Marvel was made canonically queer, we have also seen what happens when these media conglomerates try to make a “progressive statement” about representation – we get Avengers: Endgame director Joe Russo acting in a cameo as “Marvel’s First Gay Character,” or the throwaway lesbian kiss in The Last Jedi that was framed as a historic moment for Disney. This is not to say that Taylor Swift is the same as these corporations – she has long displayed a genuine love and appreciation for her fans, once proclaiming to them, “you are the longest and best relationship I’ve ever had.” And she did write “You need to Calm Down” as a sort of love letter to queer fans as well as a statement about passing the Equality Act, and despite its silliness, it did make some queer fans feel seen.

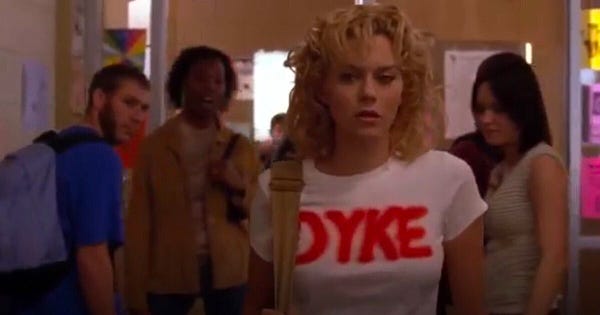

Indeed, though it would be lovely if Taylor Swift wrote a song from a lesbian or queer perspective, she has no real obligation to do so. But, regardless of whether or not Swift herself is actually queer – and personally, I don’t believe in publically speculating about someone’s sexuality, but DM me and we can talk – her songs exist in the world to be understood by fans in a multitude of different ways. (See a panel from the comic below, based on a sapphic interpretation of ‘betty.’)

Just because Captain Marvel and her “best friend” Maria are not canonically queer does not mean we cannot interpret it as such (and interpret, we do), nor does it mean Captain Marvel is not in a very real sense queer to us. Anyone familiar with fan fiction knows that the idea of authorial intent doesn’t always hold water among fans who are as invested in a particular media property as much (if not more so) than its creators. Despite the fact that we are often disappointed, and indeed, baited, by popular media, our ability to define aspects of pop culture as queer is something that can never be taken away from us.

In this sense, although most Taylor Swift fans love and respect Swift as a person, queer fans also find and take comfort in queer elements of her songs that she may or may not have (depending on your interpretation) intended to put there. It’s not a contradiction to honor and respect her songwriting process and the way she puts so much of herself into her songs and also define her songs as queer regardless of what she says about them.

While it is understandable that some fans were upset that Swift has commented on the “official” meaning of ‘betty,’ this does not make the song any less queer. Indeed, this impulse to be upset with Swift herself reflects a larger issue with fan culture more broadly, wherein fans believe their favorite artists owe them something more than simply producing the music or films that they love. All we can ask from Swift is what she has always given us – her thoughtful, personal songs, and her desire to share them with us. While we can and should ask for better representation in the media, the community of sapphic Taylor Swift fans that have coalesced around these songs has been an unexpected blessing from an artist who was once considered the pride of straight white America. Many of us feel seen by her music, and no one call tell us otherwise.

If we say ‘betty’ is queer canon, then it is! No takebacks.