In a Newly Unearthed Novel, Simone de Beauvoir Reflects on a Queer Friendship

'Inseparable' tells of Beauvoir's lost love

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet, monthly playlists, and a free sticker.

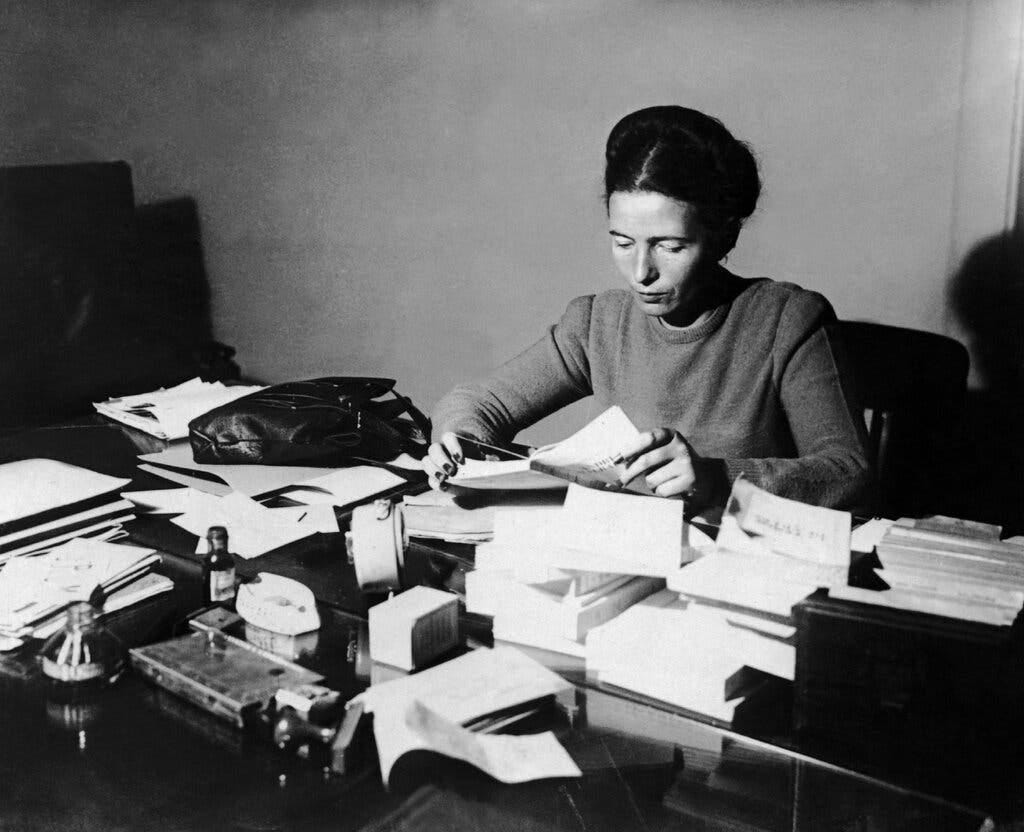

The life and work of Simone de Beauvoir, perhaps the most famous French woman writer of the 20th century, cast a long shadow. A renowned feminist thinker, Beauvoir was a key figure in the postwar existentialist movement alongside her famous companion, Jean-Paul Sartre. Her most renowned piece of writing, The Second Sex, was first published in 1949 and translated into English in 1953. Even if you’ve never read a lick of the 700-page book, you’ve probably heard its most famous passage: "One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.”

In the years following its release, The Second Sex became a foundational text for second-wave feminism. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, often credited as the book that launched the feminist movement of the 1960s, takes direct inspiration from The Second Sex. Beauvoir’s magnum opus continued to influence culture and theory long after her death in 1986. Judith Butler based their concept of gender performativity on Beauvoir’s famous quote, which Butler sees as an early formulation of the distinction between sex and gender.

Beauvoir’s bohemian, intellectual lifestyle has become as much a part of her mythos as her writing. At the age of 21, Beauvoir met Jean-Paul Sartre, the famed existentialist known for catchy slogans like “Hell is other people.” Beauvoir and Sartre were famously in a polyamorous relationship for decades, never living together and even sharing sexual partners at times. Beauvoir was known to sleep with men as well as women, though her relationships with female students have long generated controversy.

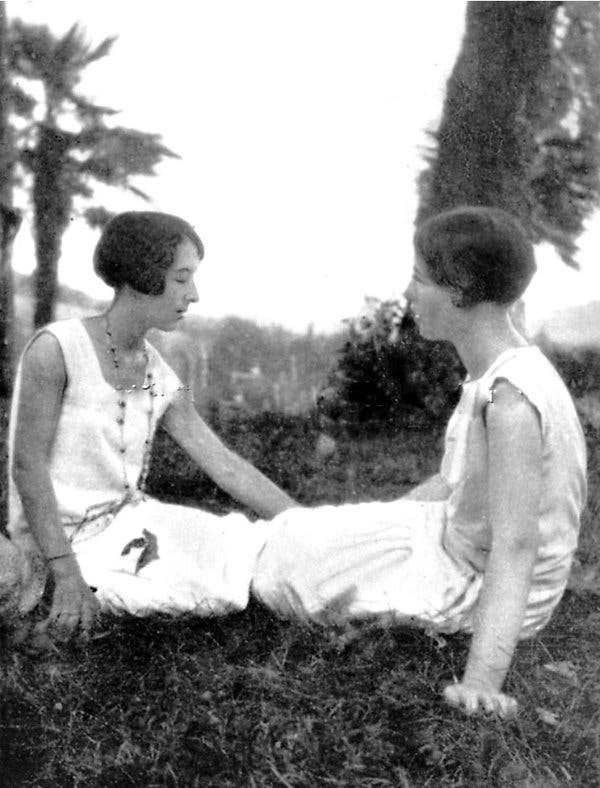

There is one aspect of Beauvoir’s story that often gets lost in the shuffle. When she was a girl, Beauvoir had a best friend named Élisabeth Lacoin, also known as Zaza. Beauvoir loved Zaza dearly, and when she tragically died in 1929 at the age of 21, Beauvoir was devastated. Zaza’s death and legacy haunted Beauvoir’s work for years, and she weaved the story of her friend into four different pieces of writing. The most famous of these works is Beauvoir’s autobiography, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, first published in 1958. In her memoirs, Beauvoir lays out the life-changing effect of Zaza’s passing. “For a long time I believed that I had paid for my own freedom with her death,” she writes.

Beauvoir’s fifth attempt to memorialize Zaza remained unpublished for seven decades. In 1954, Beauvoir wrote a short novel detailing her and Zaza’s relationship, using the aliases Sylvia and Andrée to tell their story. As Beauvoir tells it, Sartre “held his nose” at the novel, and she agreed with his assessment. “The story seemed to have no inner necessity and failed to hold the reader’s interest,” she writes in her memoirs.

Released in 2020 in France and 2021 in the United States, Inseparable marks the first time Beauvoir’s novel has seen the light of day. Published by her longtime friend and adoptive daughter Sylvie Le Bon-de Beauvoir, the book sheds light on a delicate time in Beauvoir’s early years. From an ideological standpoint, the novel tells of the author’s radicalization – her political education through the most intimate relationship of her adolescent life.

Beauvoir describes Zaza (aka Andrée) as a vivacious, fascinating, and unique person who was constrained by her circumstances, including restrictive religious practices and bourgeois social norms. Beauvoir sees Zaza’s death, and the fact that she wasn’t able to live the life she dreamed of, as a brutal example of patriarchial conditioning, a topic she would return to again and again throughout her career as an intellectual. More than a decade before the term was coined, Beauvoir makes a strong case for the personal being political. Indeed, the novel serves several functions. It’s a coming-of-age story, a romantic tragedy, and a nascent political manifesto all in one.

Readers of Inseparable can agree on one thing: Sylvie (Simone) loved Andreé (Zaza). The question that remains up for debate is what kind of love was it, and does the answer to this question even matter? There are two schools of thought here. Some readers see their relationship as a platonic – albeit passionate – friendship, refuting any hint of any romantic or erotic connection. In her introduction to the novel, Margaret Atwood describes their dynamic as “a many-layered and intense friendship.” A feature in Penguin characterizes Sylvie’s feelings for Andreé as “unrequited platonic love.”

In a book review blog, Lolly K Dandeneau describes the book as “a love story, in essence, the first love that many girls feel for their best friend. A chosen sister, if you will, one that indulges and challenges you.” Sylvie Le Bon-de Beauvoir has chimed into this conversation as well. Le Bon told The Guardian “It’s absurd to speak about a lesbian relationship [in the novel] when desire and the body are not involved.” As for Beauvoir’s take on the relationship, she once told a biographer “You can explain my feeling for Sylvie by comparing it to my friendship with Zaza.” (Le Bon was Beauvoir’s companion for over 25 years, and while Beauvior formerly adopted Le Bon several years before her death, Le Bon maintains that it was a legal decision so Le Bon could access and preserve Beauvoir’s work, not a familial one.)

Others contend that Sylvie’s feelings for Andreé (or Simone’s feelings for Zaza) were clearly romantic, and even erotic in some moments. Philosopher Paul B. Preciado is adamant that the relationship between the two women was a romantic one. “No, it was not friendship. It was a lesbian passion,” he writes. Preciado suggests that Zaza’s death changed Beauvoir’s life in more ways than one, foreclosing the potential of queerness as a social or political identity. “What died for Beauvoir was the possibility of lesbian identification,” he argues.

An article in France 24 calls the book a “tragic lesbian love story,” while Forbes, attempting to cover all its bases, describes Inseparable as a “tragic LGBTQ love story. The Wall Street Journal maintains that Simone fell in love with Zaza the first time they met at age nine. Though she later denied any connotations of lesbianism, in her afterward, Le Bon describes the relationship between Sylvie and Andreé as “love at first sight.”

However you want to define Beauvoir’s feelings for Zaza, it’s clear from her writing that Zaza was one of the most influential figures in her life. As far as her canonized life story goes, Zaza upends the idea that Sartre was the primary instigator of Beauvoir's intellectual education, and indeed, that he was her first love. If existence precedes essence, as Sartre famously theorized, then perhaps Beauvoir’s essential character was shaped more by Zaza than by him.

Does it matter what Beauvoir has said about the relationship, or about her sexual identification (or lack thereof)? Certainly, no one wants to overwrite Beauvoir’s account of her life story. Yet the book, including the letters exchanged between the real Simone and Zaza, does appear to represent a lesbian narrative that may have been overlooked as such in an earlier time.

Reading history through a lesbian lens has long been a controversial practice, though so many historical documents – particularly letters – indicate lesbian desire in fairly obvious terms. Think of the longstanding straight-washing of Emily Dickinson, despite her relationship with her first love, Susan Gilbert, and the hundreds of passionate letters they sent over three decades. Or the amorous letters between two 12th-century nuns, overlooked as an instance of lesbian desire for many years. The silences in Beauvior’s work, and the moments when desire and longing slip through the cracks, speak volumes.

Inseparable itself provides evidence for a lesbian reading of the relationship, despite various denials of this characteristic. In one sensuous moment, Sylvie, imagining Andreé’s burns, notes "I thought of her swollen thigh, under her little pleated skirt." Counter to claims that their relationship is a “cerebral love,” this passage indicates that the mind is not the only place where love and desire reside. Later, Beauvoir recounts the nature of her passion in more romantic terms. “From the day I met you, you were everything for me,” she writes in one passage. “Life without her would be death,” she writes in another.

If we turn to her most famous work, The Second Sex, we begin to see a pattern of both lesbian acknowledgment and disavowal. In one chapter, Beauvoir makes a bold claim, stating that “nearly all girls have lesbian tendencies,” but that “these tendencies are barely distinguishable from narcissistic delights.” Though she acknowledges queer feelings, Beauvoir refuses to make a case for a distinct lesbian identity or the power of lesbianism as a social and political stance. Nonetheless, she does contend that gay love can be a meaningful experience for some. “The homosexual experience can take the shape of true love,” she writes, and it can even “awaken or give rise to a lesbian vocation.” But she walks back this possibility rather quickly, noting that “most often, it will only represent a stage.”

For all her trivialization of lesbian love, Beauvoir seems to idealize it as well. “Between women, love is contemplation,” she suggests. “Separation is eliminated, there is neither fight nor victory nor defeat; each one is both subject and object, sovereign and slave in exact reciprocity.” This kind of equality, an almost utopian sort of love between two women, was something Beauvoir desired with Zaza but never achieved, both because Zaza’s feelings for her were not equal in passion, and because Zaza’s life was cut short.

In the earlier passage about the universality of sapphic desire, Beauvoir undermines her own position about the unimportance of lesbianism, writing that it is “the sweetness of her own skin, the form of her own curves, that each of them covets.” We can recall here the moment in Inseperable when Sylvie hones in on Andreé’s swollen thigh. As Merve Emre writes in The New Yorker, “Desire, when improperly acknowledged, gives birth to a theory that tells on its author.”

With all of these inconsistencies and contradictions, how can we frame Simone and Zaza’s love in a way that’s comprehensible in the context of Beauvoir’s life and work? One option is to turn to a feminist theorist whose most famous essay was published in book form the year of Beauvoir’s death. In "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” Adrienne Rich outlines her theory of compulsory heterosexuality, in which women of all walks of life are funneled into the system of heterosexuality and heterosexual reproduction. Shortened to “comphet” in the 21st century, the theory has since become common parlance among younger queer folks, especially on TikTok.

While Beauvoir mostly discards the idea of lesbian desire and identity as a potential political act, Rich makes no such renunciation. A less-discussed corollary to Rich’s argument is the idea of the lesbian continuum, which describes “a range – through each woman’s life and throughout history – of women-identified experience, not simply the fact that a woman has had or consciously desired genital sexual experience with another woman.” Broadening the scope of lesbianism in this way works to de-center the institution of heterosexuality, as these lesbian connections become the organizing force of women’s relationships.

The concept isn’t about lesbian identification, but rather about recognizing instances of “marriage resistance” that fall somewhere along this continuum. Still, this isn’t to say that lesbianism as an identity loses all meaning. In a more individualistic sense, Rich defines lesbians as those who “have made their primary erotic and emotional choices for women.” The notion of choice is significant here. It’s not that lesbians are choosing to be attracted to women, but they are choosing to live out these desires in an authentic, public manner. This is what makes the existence of lesbians so powerful.

Free will and choice are also central to the philosophy of existentialism, of which Beauvoir was a key figure. Think of the famous Sartre quote: “Man is condemned to be free. Condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.” Of course, what Rich points out is that the system of compulsory heterosexuality is extremely dominant and powerful, and it is challenging to escape its clutches. Beauvoir makes a similar argument about patriarchy, taking a pseudo-scientific approach to the study of sex, gender, and socialization. Free will, in these contexts, is more difficult to exercise.

Though Rich doesn’t reference Beauvoir in the essay, she does take aim at her feminist contemporaries, many of whom she sees as overlooking a key point of analysis. Of these feminist writings, Rich contends that “each one might have been more accurate, more powerful, more truly a force for change had the author dealt with lesbian existence as a reality and as a source of knowledge and power available to women, or with the institution of heterosexuality itself as a beachhead of male dominance [emphasis mine].” This lack can be found in Beauvoir’s work as well, though Inseparable nonetheless paints a compelling picture of lesbian desire as an activating force in one’s life.

If we take Rich’s theory at face value, Beauvoir clearly existed somewhere along the lesbian continuum, both during her relationship with Zaza and her later years. What does that mean for her legacy, or our understanding of her work? In the case of towering intellectual figures like Beauvoir, it’s difficult to separate the writer from her life, or at least the legend of her life. The experience of lesbian desire and the possibility of bisexual identification both complicate and confirm her philosophies about gender and society. Lesbian love is both fundamental and incidental, depending on where in her oeuvre you look.

The notion that political opinions are influenced by personal experiences or feelings – even unacknowledged ones – is not a novel idea. As Inseparable suggests, it was Beauvoir’s intimate feelings for a young woman, not a man, that sparked her political awakening. Speaking about her relationship with Zaza many years later, Beauvoir explained: “I have kept my nostalgia for that my whole life.” Even if Beauvoir doesn’t describe it that way, it’s not a stretch to read lesbian love, desire, and longing into this story, in both its fictionalized and biographical forms. Friendship and romance aren’t as far apart as we might imagine, and in some cases, they’re nothing short of inseparable.

Bravo and thank you

Kara Deshler: This story is beautiful.

As a man married 51 years to (and 53 years in love with) the Love of My Life, Nancy, I have long come to believe that the best relationships are long-term lesbian love.

It roils me that women suffer such violence and violation in our society.

I think in lesbian love there is transparent communication, mutual respect, and respect of boundaries. I think in such a relationship, the person can develop her freedom with the best of support.

As a man that loves his wife, I recognize my own limitations.