Forever in a Photograph

Archiving Joy in 'Elisa & Marcela' and 'Aimee & Jaguar'

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. A paid subscription gets you more writing from me and will help me keep this newsletter afloat. Consider going paid! The following contains major spoilers for both films in question.

We all crave stories that touch us in some way. Stories that elucidate certain enduring truths, enliven our sense of history, or awaken us to the possibilities of the future. In recent years, a peculiar sub-genre, (one I have written about before), has emerged as an especially visible example of queer media. In certain contexts, the prominence of lesbian period pieces has become something of a joke among queer women and sapphics, their heightened visibility both amusing and frustrating. But there are surely still threads we can unspool, lessons that can be gleaned from these enterprises.

Within this genre, if you can even call it that, there is a smaller sub-genre, which includes narratives based on real-life women and queer people, many of whom were previously unknown (or under-discussed) by the general public. Projects like the popular BBC series Gentleman Jack, which follows 19th-century lesbian Anne Lister, or 2018’s Vita & Virginia, or even Paul Verhoeven’s blasphemous lesbian nun romp Benedetta, all work to flesh out narratives that previously existed only in a fragmented form. The best of these films and series are able to creatively fill in the gaps, creating presence where there was previously an absence. By recovering these histories, importance is then retroactively signified.

While there are numerous films I could pull from in order to illustrate these points, I will focus on just two. The first film is 2019’s Elisa & Marcela, which was directed by prolific Spanish filmmaker Isabel Coixet. Elisa & Marcela is based on a true story that revolves around the first recorded same-sex marriage in Spain, which occurred in 1901. The story follows the titular characters as they meet as schoolgirls in Spain just before the turn of the century. They develop a very strong affection for one another, but are separated when Marcela gets sent to boarding school.

Three years later they reunite in a small town in Galicia where they are both schoolteachers. They are initially ecstatic to be reunited, but the villagers soon become hostile toward the women. In order to evade suspicion, Elisa leaves for a few days and returns as a man named Mario, the name of her deceased cousin. They are married by a local priest, but the villagers become suspicious once again and they are forced to flee. They escape to Portugal, but are captured and sent to prison. Marcela has a baby – part of their ruse as a married couple – while they are both incarcerated. The pair eventually escape to Argentina, leaving the baby behind.

Coixet's film is intriguing because out of all the lesbian period pieces out there, it is one for which there was very little firsthand evidence to draw from. We do know that Elisa and Marcela were legally married in 1901 and subsequently arrested, but we know nothing of what became of them following their escape to Argentina. Whatever written communications that may have existed between the two women have since been lost. We do know that their marriage was never annulled despite their capture, so they remained married for as long as they both lived.

This vacancy presents a beguiling problem for Coixet to solve. As Sharmane Tan writes in Girls on Tops, “If lesbian existence is plagued with absence, then Coixet’s work self-consciously indicts itself in this precarity by persistently reminding us that history is fragile, prone to mishandling and abuse.” Elisa & Marcela is quite lyrical and poetic, choosing to portray the relationship through the imagery and language of dreams rather than facts. The film wasn’t especially well-received by critics, many of whom seemed to think it lacked some sort of emotional resonance or necessary passion. (I will add here that certain male critics had similar things to say about Portrait of a Lady on Fire, which to be fair, is the better film of the two.) Regardless, what the film occasionally lacks in momentum it makes up for in its arresting desire to catalog a love unspoken.

1999’s Aimee & Jaguar is a very different film from Elisa & Marcela (despite their titular similarities), but the two films share a commitment to artfully filling in the gaps. Based on the non-fiction book of the same name, the film follows a doomed love affair between two women in 1940s Berlin. Lilly Wust is a housewife with four children who is married to a Nazi officer. Felice Schragenheim is a young Jewish lesbian and a member of the underground resistance. Felice begins pursuing Lilly after a chance meeting, and the two women unexpectedly fall in love. Throughout their courtship they constantly exchange letters, referring to one another as their alter egos – Aimee and Jaguar.

I’m sure I don’t need to tell you that their story does not end happily. After deciding to stay in Berlin with Lilly instead of escaping the country with her friends, Felice was captured by the Gestapo and sent to a concentration camp where she would eventually meet her death. Lilly avoided prosecution for helping Felice because she was the mother of four children, and tried visiting Felice in the camps several times. Lilly would stay in Berlin for the rest of her life, dying in 2006 at the age of 92. Her gravestone serves as a memorial for Felice.

Unlike Elisa & Marcela, a significant amount of source material existed for the producers of Aimee & Jaguar. In the 1990s, Lilly sold the rights to her love story to journalist Erica Fischer, who went on to write a book about the couple. She had their numerous letters, Felice’s poetry, and Lilly’s own memory of events to draw from. The film was then adapted from Fischer’s book. Though ravaged by grief, Lilly never forgot Felice, and remained hopeful all her life. As she told a journalist in 2001, “Twice since she left, I've felt her breath, and a warm presence next to me. I dream that we will meet again - I live in hope.”

Letters are a cornerstone of romance in each film. They serve as a fossilized archive, a legacy of a romance frozen in time. To be sure, letters are central to most historical romances and historical films and series in general, because they were the most common and accessible form of communication for many centuries. But for those invested in lesbian and queer history, letters take on an added significance, as they remain one of the key pieces of evidence that lesbians have existed for as long as the written word has. Anne Lister (the titular Gentleman Jack), for example, was a prolific letter-writer and journaler, and her writings are the basis for much of the show. Arguably the most famous sapphic letter-writers are Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, whose extensive letters have even been immortalized in the form of a Twitter bot. And let us not forget all those love letters between medieval nuns that prove that they were doing a little more than just sweeping up and praying to God.

The archive of letters – whether material or imagined – was a significant part of the filmmaking process for both films. For Coixet, she had very little to work with in the way of physical evidence. A book was written about Elisa and Marcela in 2008, but we still know very little about the thoughts and feelings of the women themselves. As an exercise, Coixet had actors Natalia de Molina and Greta Fernández write letters that might have been passed between the two women. Coixet found the practice so intriguing that she incorporated the letters into the film. There are several sequences that show Elisa and Marcela, each facing the camera, as they read the letters they wrote to one another during their three years of separation. In this way, Coixet created a history that has been lost to time, or may have never existed at all.

In Aimee & Jaguar, the archival material at director Max Färberböck and writer Rona Munro’s disposal was much more extensive. Though she shared the letters with Fischer during the writing process, Lilly always kept Felice’s letters close by. For as long as she lived, Lilly kept Felice’s letters in a suitcase and wore its key around her neck. "I open it every August 21 [the anniversary of her departure] and indulge myself with memories," she told The Guardian. In the film, such memories are brought to life, immortalized once more within its frames.

In both instances, these stories sound almost too good to be true. “Good” not in the sense of their perfect felicity, but rather because of their epic melodrama, and the astounding fact that these women were able to carve out lives for themselves, however briefly. In his review of Aimee & Jaguar, Roger Ebert wrote that “This is the kind of story that has to be true; as fiction, it would not be believable.” The same could be said of Elisa & Marcela, whose characters embody an astonishing belief in themselves despite violent opposition to their way of life.

Indeed, what is most compelling about both films is how they highlight the joy these women were able to fight for, hold on to, and envelop themselves in, despite the circumstances. In Aimee & Jaguar, the day Felice was arrested by the Gestapo, she and Lilly have a picnic at a lake before they are intercepted on their way home. The moment prior to Felice’s arrest, like many others in the film, is filled with lightness and laughter – not something one would expect from a love story in 1943 Berlin. Elisa and Marcela’s story contains many of these moments too. There is the first act of the film, where they fall in love as schoolgirls, with Marcela purposefully forgetting to bring an umbrella so Elisa will be “forced” to help her dry off in the bathroom. Then there is the mirthful moment when they go to the beach and Marcela convinces Elisa to go swimming even though she is afraid of the ocean.

There are other, more overtly passionate moments, too. One of the most prominent motifs in Elisa & Marcela is an octopus, which appears several times over the course of the film. The most striking image comes when the women incorporate an octopus into their sexual practice. They are entirely comfortable in their own skin, away from prying eyes (or so they think). Later in the film, Marcela comes home one day to find Elisa naked on their bed, covered artfully in seaweed. It’s not as if Coixet is suggesting that these two women did in fact engage in this behavior, or even that they might have. Rather, these moments of unabashed pleasure exemplify the film’s supposition that such “perverse” joy is and was possible, even if it may not have occurred in these precise circumstances

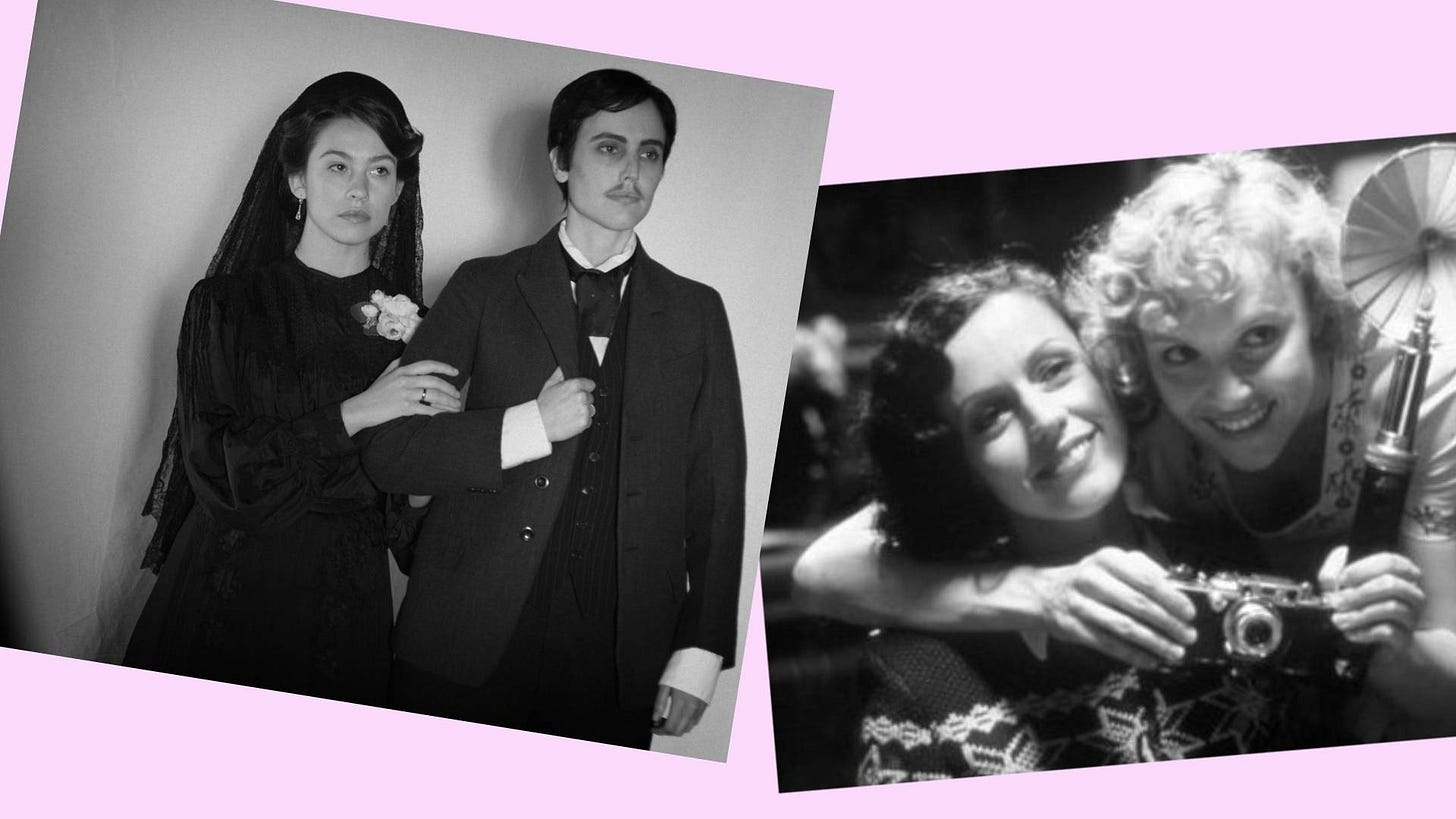

Both films are bookended by moments of cathartic joy – the image of a happy ending that these women must have desired so greatly. Specifically, the two films conclude with a photograph, or at least an allusion to one. Elisa & Marcela ends in Argentina – where the women are thought to have escaped – in the year 1925. Marcela’s daughter has come to visit her, seeking answers about the circumstances of her birth and subsequent adoption. Marcela’s daughter asks her mother, was it worth it? Marcela doesn’t answer.

Instead, she wipes the tears from her face and walks towards a woman with long gray hair who is approaching on a horse – Elisa, we presume. The frame begins to flicker and become grainy, as if it were an old photograph from the previous century. Is this real? The flickering image seems to ask. By pointing our attention to the fact that this is an image, a photograph, constructed as if it were from a distant past, we are reminded that this very likely was not how the story played out. Rather, Coixet has dealt with the problem of lesbian invisibility by constructing her own version of the story.

The final scene of Aimee & Jaguar also deals with the inevitability of loss by freezing an image within the frame of a photograph, a memory. The last scene of the film is a moment of decadent joy. Felice and Lilly are celebrating with their friends, eating cake, drinking champagne, and generally carrying on. (Presumably, it’s Felice’s birthday – she turned 21 in March of 1943.) Lilly asks Felice what she wants, and she responds in a typically grandiose manner. “Me?... You, all of you, everyone. Everything! But I'd be satisfied with one single moment... ...so perfect it would last a lifetime….For example, this one here is great. I don't want "forever. " I want "now!" Now! Now! Now! I want loads of "nows!" And I want them till I turn old and gray. And besides, I want more cake.”

Lilly then takes a picture of Felice, who is smiling brightly at her. Lilly, also not satisfied with just one single “now,” asks Felice to pose once more. “Again!” Lilly says. It’s the final line of the film. You can almost imagine that this night of joy goes on forever, even though you know, quite decisively, that it does not. Indeed, that is the power of photography, and the moving image more broadly. The power to extend time, to make one moment feel like a lifetime.

Photography is important to the legacy of both couples from an archival standpoint, too. For Elisa and Marcela, their wedding photo – where Elisa is dressed as Mario – is one of the only photographs of them that exists. For Felice and Lilly, the only photos of them as a couple were taken on that fateful trip to the lake just hours before Felice was captured (see above). In the photos, they are kissing and embracing in their bathing suits. (We see this moment in the film as well, with the two women giddy from their love for one another.)

Obviously, photography is the medium of filmmaking as well, and both films are highly aware of the advantages of this visual medium. For Elisa & Marcela, there was very little in the way of a material archive for Coixet to draw from. The film uses the lyrical, poetic capabilities of filmmaking to weave a story that is based not in absolute fact, but in emotional intensity and resonance.

In Aimee & Jaguar, for which there is a much more substantial archive, the filmmakers had the privilege of being able to draw from both memories and artifacts in order to construct a story. We see photography within the film as well, as both Lilly and Felice are frequently seen taking pictures of each other. While the film itself is keen on preserving this story and highlighting these precious moments, so too were the women themselves, we are reminded. Indeed, the film would not exist were it not for Lilly Wust’s desire to share her story with the world, something she became committed to doing following a neo-Nazi attack on her home in the 1980s.

From loss emerges a kind of catharsis and joy – inspiration, even. That then, is the legacy of these films, and the stories they bring to life. Whether creating presence where the once was absence, or noise where there was once silence, these films speak as only love stories can – with infectious elation and an abiding desire to live forever.