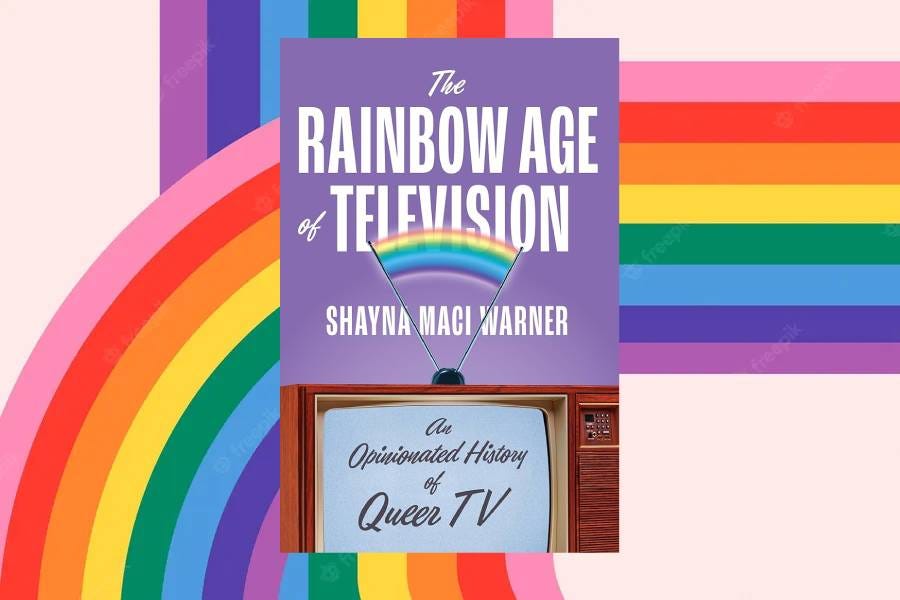

'The Rainbow Age of Television' Tells of Queer TV's Past, Present, and Future

On Shayna Maci Warner's Illuminating Book

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet, monthly playlists, and a free sticker.

In The Rainbow Age of Television, Shayna Maci Warner chronicles the history of LGBTQ people on television – the where, when, and in some sense, the why. Before commencing this admirable project, Warner begins with a caveat, and a question. Does representation still matter? As Warner puts it, a cynical – but not unfair – definition of representation is as follows: it’s an “ ideological tool, a marketing ploy, a way to fundraise for organizations that make money off the image of young and eager queers.”

The great innovation of television was that it could transmit into the heart of America – the home. With this came more real estate for advertising than ever before. Questioning TV’s ability to change things for the better, Warner asks, “Can capitalism bend that much-evoked moral arc of the universe forward?” Indeed, in recent years, queer visibility on screen has resulted in alarming backlash from the right, and for the most vulnerable in our community, being more visible can mean being less safe.

Considering this book was written and published, one imagines Warner came to the conclusion that while representation has its pitfalls and can be used to disguise the insidious inner workings of capitalism, it does still matter enough to people to warrant serious consideration. One of the most compelling aspects of the book is how it tracks the appearance of queer and trans people on TV, across the decades and across genres. As Warner notes, in order to understand where we are and where we’re going, we need to first understand where we’ve been.

There’s much to discover in this regard. The first implicitly gay character on television dates all the way back to 1950 with Ernie Kovac’s limp-wristed Percy Dovetonsils, a character who emerged on sketch television. Unnamed – though clearly coded – queer characters continued into the 1960s on shows like Asphalt Jungle. Many of the earliest gay characters on television first appeared on procedurals, with the first “expressly named gay character” appearing on the pilot episode of N.Y.P.D. in 1967. This trend continued into the 1970s, with the first queer women couple appearing on The Bold Ones: The New Doctors in 1972.

The 1970s saw the first appearance of a recurring gay character, named Peter Panama, on a 1972 series The Corner Bar, though he wasn’t particularly well-received by gay groups because of how stereotypical he was. As the decade continued and legendary TV producer Normal Lear arrived on the scene, queer and trans characters continued to proliferate. All in the Family famously featured gay characters, while The Jeffersons featured an episode with a trans character.

But there are two groundbreaking Lear productions that have sadly been forgotten about. 1975’s Hot 1 Baltimore features a gay couple in the main cast, and All That Glitters, from 1977, featured a trans woman as a recurring character. Neither of these shows are available to watch online, and only a few episodes are housed in archives.

This loss of history is the result of television’s ephemerality. For many decades, TV was not considered worth preserving, and when early TV was recorded, the tapes were often recorded over or thrown away. Things haven’t gotten much better with the advent of streaming, as streaming services have no incentive to keep their content accessible for audiences and have even begun taking original content off their platforms entirely. As Warner notes, this is a troubling predicament for those interested in queer history and media criticism. “If we don’t know what came before, how can we ask for better?”

The AIDS crisis undoubtedly had an effect on queer representation in the 1980s, and there were several years when gay characters stopped appearing on television altogether. Nonetheless, by the end of the decade, it wasn’t uncommon to see gay characters on your screen. And yet, gay characters were still not given the same weight as their straight counterparts. For example, the 1988 series HeartBeat, which follows a group of women doctors, included a prominent lesbian couple. Though the two women lived together, they were never allowed to show physical affection like a straight couple would, leaving their relationship feeling unfinished.

The 1990s is a rich decade for queer TV history, and Entertainment Weekly dubbed it The Gay 90s, even then. The decade is most famous for the appearance of both Will & Grace and Ellen, specifically the two-part episode where the title character (and the woman herself) comes out. The 90s also birthed the so-called “lesbian kiss episode,” along with numerous recurring and regular gay characters on popular shows. (E.R., for example.) Numerous TV movies featuring gay protagonists aired in the 1990s as well, including many involving custody, children, and other hot-button issues.

The 90s saw the emergence of a new television strategy: narrowcasting. TV producers realized they didn’t have to attract a broad audience – they could instead appeal to a smaller, dedicated audience that would keep coming back for more. This meant that queer characters that didn’t fall into easy stereotypes began to appear on screen, including on teen shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Dawson’s Creek.

One of the most interesting questions Warner poses in the book pertains to the distinction between “positive” and “negative” representation, something queer folks have been arguing over for decades. Warner discusses the unique pleasure of seeing “bad” queer characters on screen, in groundbreaking shows such as Oz and The Wire. These characters are a far cry from early queer TV characters, who had little bite or power and primarily trafficked in stereotypes. Indeed, one could plot the (highly simplified) trajectory of queer TV representation like this: offensive → safe → complex (or even villainous).

As Warner suggests, when queer characters are wholly perfect or good, there’s little room for growth, so a turn toward the grey area may actually be a step in the right direction. The same is true for death on screen. Though the outrage about the Bury Your Gays trope was justified, if we get to a point where queerness becomes baked into the television landscape, a queer character dying won’t have the same devastating effect, at least not on a cultural level.

In the portion of the book focusing on non-scripted television, Warner schools readers about a genre that’s often overlooked when we discuss representation. News shows and talk shows have featured gay and trans people since the 1950s, though their treatment on these programs wasn’t the most supportive. A watershed moment arrived in 1973 with the premiere of An American Family, a never-before-seen kind of reality programming that featured a family with a gay son. Though the series generated much discussion, it would be two more decades before the reality TV genre really took off.

When it finally became popular in the 1990s, the world was introduced to the late Pedro Zamora, a cast member on The Real World living with HIV. Viewers fell in love with Zamora, and his appearance on the show was a way for him to educate the public about what it means to be gay and have HIV. (José Esteban Muñoz dedicated a chapter of his influential book Disidentifications to Zamora.) A few years later, shows like Big Brother and Survivor premiered, and gay contestants were part of the show from the very start. Top Chef is certainly a part of this conversation as well, and Warner conducts an illumination interview with Top Chef winner Melissa King about her experiences on the series.

Local cable television, one of the most overlooked aspects of broadcasting, holds a surprisingly critical place in queer TV history. As Warner notes, gay-specific shows emerged on local cable access as early as 1977 with NYC’s The Emerald City, which included news, interview segments, and musical and comedy performances. Similar shows popped up in other cities for the next decade, and in 1992, a gay news show called In The Life aired its first episode, becoming the first show of its kind to be broadcast nationwide. This is another piece of history most are unaware of today, and Warner is wise to include it in the book.

The last few years on television have been rife with reboots, including reboots of beloved queer shows like Will & Grace, Queer as Folk, Tales of the City, and of course, The L Word. Warner suggests that most of these reboots are too focused on re-writing the sins of the past rather than creating something fresh and exciting. Indeed, this kind of restorative impulse characterizes the TV landscape today, as producers are all about keeping up appearances and transmitting a sense of moral righteousness. (See the previous discussion of complexity vs perfection.) This is a reductive, hollow way of looking at representation, a framework Warner criticizes at the outset.

Queer TV today is in a state of limbo, Warner argues. While there is more queer television than ever before, cancellations are increasing at a rapid rate as well. Television has always been a transient business, but for fans, these queer TV cancellations feel personal. To combat this increasing sense of precarity, Warner suggests we put our energy behind queer creators first and foremost, supporting people in the industry looking to make art that moves, affirms, and challenges us.

To that end, the book includes eight interviews with creators and actors involved in the making of queer television, including Lilly Wachowski, Jamie Babbitt, and Tanya Saracho. These conversations give readers a sense of what goes on behind the scenes in the making of queer TV, from the joy of working with queer creatives to the frustrations of network constraints. (For example, Jamie Babbit, who directed several episodes of The L Word, notes that Showtime balked at the idea of casting butch lesbians on the show because they still wanted to appeal to a male audience.)

The history Warner lays out here is as illuminating as it is thought-provoking. As Warner reminds us, queer people have always been here, and that includes on the airwaves. Though television aims to transmit a capitalistic product into people’s homes, it can also be the source of moving, innovative, and yes, exasperating, art. Fighting for its continued existence is a worthy cause, as is preserving its history.

something lesbian this way comes

In Thailand, women are kissing, in witchland, they're fighting, and in England, they're experiencing gay love at the beach. Thank God – someone finally styled Billie Eilish properly.